“Chino Ranch Chopped Salad” is featured on the menu at Spago, Wolfgang Puck’s Hollywood restaurant. “Chino Ranch Salad” also appears on the menus of a number of lesser known restaurants, many of which don’t buy their vegetables at the Chino family’s modest stand just inland from Del Mar, California, but don’t mind capitalizing on its renown.

This Japanese American family has been the subject of a lengthy New Yorker magazine profile, newspaper articles, and a recent NBC news segment with Tom Brokaw. The unique quality and variety of the Chino farm produce, the fact that four of the children carry on the tradition of the Issei parents, and the affluent and knowledgeable customers and friends they attract, add to the mystique. There is also the sense that the Chino family exists on an island in time. Mark Singer wrote in the New Yorker article, “They have made of the farm a separate sovereignty, a life and enterprise totally outside the mainstream.”

Alice Waters, cookbook author and owner of Chez Panisse in Berkeley, California writes, “The Chinos have made an art of farming. For two generations now, they have tended their land with an inexhaustible aesthetic curiosity, constantly seeking out new and old varieties of dozens of fruits and vegetables from all over the world, and planting and harvesting year round. Virtually all their produce is sold at their own stand, which looks as glorious in the winter, full of a staggering array of shades of green from the almost black leaves of tatsoi to the glowing blanched centers of heads of curly endive, as it does in the summer, with displays of a many as seventeen kinds of tomatoes, of as many different colors.”

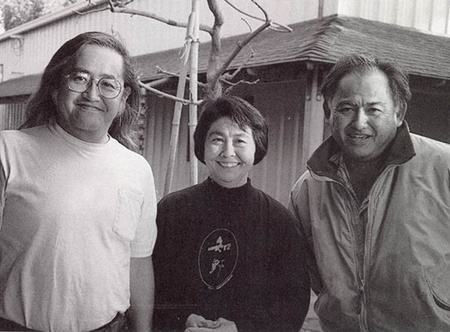

Tom Haruya Chino shrugs off the family’s fame. “We’re the same people as we’ve always been,” he says. Tom, the youngest of the nine Chino children, is usually the designated family spokesman. Brothers Frank (Koo), Fred (Fumio) and sister Kazumi also work the 50 acre farm. Tom thinks that their close ties to Japan may help to explain the family’s unique character. “My father wasn’t very good at integrating with the community,” Tom says. “We were rather isolated.”

The family patriarch, Junzo Chino, never forgot his Japanese roots, in a small seaside village 100 miles south of Wakayama. “There was just my father’s sister left in the village,” Tom recalls, “and she sold the family property. My father felt a tremendous loss at that.” Eventually Junzo returned and bought land, and in the ’60s, built a house there. The Japanese connection is also maintained through a university exchange program begun by Junzo to train Japanese farmers. Over the years many students have lived and worked with the Chinos, learning farming principles and sharing their life.

Junzo Chino was studying to be a Buddhist priest when he was sent by his father in the early 1920s to locate his brother in America. The two eventually connected in California, and both became migrant agricultural workers. Hatsuyo Noda came to America in 1922. Her family moved from Wakayama to Oxnard, California, where her father farmed celery. The two families were acquainted, and in 1930 Hatsuyo and Junzo were married. They first ran a fruit stand in Los Angeles, then began farming near Venice. In 1937, they moved to Carlsbad, in Northern San Diego county, where they bought a house and three acres of greenhouses and raised vegetable seedlings and flowers. When war came, the family was sent to the camp at Poston, Arizona.

Kazumi, the third child born in 1933, remembers how hard it was to leave the family’s animals. She also remembers that her meticulously well organized mother packed away photographs and family treasures and left them in the Carlsbad house, in the care of a trusted Caucasian acquaintance. They signed away their property to him in order to protect it from being confiscated, and later discovered that he had sold everything. Kazumi still wonders what happened to the photos and mementos. “Sometimes I imagine that there’s a closet somewhere full of my mothers’ things,” she says. She also recalls that her mother, unable to grow her beloved flowers in the arid Arizona climate, made quantities of crepe paper flowers, used to create funeral wreaths, wedding bouquets, and decorations for the camp residents.

In 1945, the family, which now included two girls and five boys, (Fred and Tom were born later, in 1947 and 1949) was released from camp and moved to Los Angeles. They returned to San Diego county in 1947. “My father had a good reputation growing crops,” Tom says. “There wasn’t any money, but a lot of people in the wholesale market knew his reputation and knew that he knew how to grow things, so they financed him. He was very successful and was able to pay off his debt in the first two years.” In 1952 Junzo bought 50 acres in Del Mar which he had been leasing.

In the post war years the Chinos grew celery, strawberries, and peppers to be shipped to the wholesale market in Los Angeles, and a variety of fruits and vegetables for their own use. Tom remembers that his parents “were very progressive in what they grew. They always grew some oddities just for the heck of it. When my parents were growing tomatoes commercially, they would grow some yellow tomatoes as well and try to sell them—unsuccessfully, because the market wasn’t there yet. They grew yellow bell peppers forty years ago, but couldn’t sell them because the market wasn’t developed.”

Eventually the older children went off to college and started careers. Kazumi came home to stay in the mid-sixties, and as their parents grew older, her younger brothers joined them on the farm. They opened the Vegetable Shop, as the roadside stand is called, in 1969. More and more of their crop was sold from the stand, and in the seventies they stopped selling to wholesalers entirely.

Hatsuyo was largely responsible for planning what to plant and where, until Tom gradually assumed that responsibility. “After we started the stand, one variety led to another,” he remembers. “We would find an example of something unusual and then we’d eat it, we’d say ‘what’s so great about that?’ So then we’d say ‘let’s see what it would be like if we grew it ourselves?’ and we’d do that. And my sister was part of finding new things, since she produces all the new plants in the greenhouse.”

“We might have been more attuned to the pure essential taste of vegetables.” Tom says. Trying to account for the unique character of the Chino farm produce. “We had the distinct advantage that my mother was a good cook. We would eat Japanese food at home and we knew how vegetables taste. And we were always around very fresh produce. We could see easily that a vegetable picked today and a vegetable the next day were very different in flavor. We knew that with the stand we could sell things that were picked that day and even when it was traditional vegetables the flavor was much better than anything you could buy at the store. And we get encouragement from the customers of course. The community we’re in is somewhat cosmopolitan—not like a big city, of course—but there are people that have money and have traveled, and their wanting to buy this produce stimulates us to search for other things that they might like.”

“Present day farming requires more technical expertise than my parents had,” Tom notes. But he also thinks that it’s possible to “get so enamored of technology you lose track of the essence of farming. My parents definitely had the understanding of the essence of what farming was about. There’s an expression, ‘The best fertilizer for the field is your shadow,’” Tom says. “My parents understood that.”

Junzo Chino died in 1990 and Hatsuyo in 1992 but their presence is still very much felt on the farm. Kazumi says that her father was “old fashioned”—his strictness, as well as his farming and teaching skills, are part of his legacy. At the seven year memorial service in Japan for Junzo, fifty of his former students came to honor him. Their recollection was that he was “tough but fair,” Tom says.

Tom remembers that Hatsuyo had “more of a sense of humor” than his father and was an incredibly hard worker. Their parents taught and passed on traditions and values by example. “They didn’t actually tell you ‘this is what you do, this is what not to do.’ That was something that had to come from us,” Tom says.

On a bright January day, Kazumi apologizes for the display at the stand. In winter the Chinos grow 60 different varieties of produce, including trays of multicolored lettuces, broccoli, cauliflower, spinach, cabbages, carrots and other root vegetables, peas, fava beans, baby artichokes, radishes, and herbs. “We don’t have so much at this time of year,” she says. Nevertheless, the parking lot fills with expensive cars and customers in their designer clothes lining up each morning. The Chinos deliver only to Chez Panisse and Spago. Everyone else, from chefs in upscale restaurants to Rancho Santa Fe housewives, has to come to them.

*This article was originally published in the Japanese American National Museum Quarterly, Spring 1997.

© 1997 Japanese American National Museum