A distinct pattern of Japanese migration to Australia emerged after the Meiji Restoration in 1868, when Imperial rule was reinstated and Japan’s ports were opened after centuries of feudal seclusion. For the first time, ordinary Japanese citizens could go abroad.

From the 1870s until World War II, more than a hundred thousand Japanese voyaged to Australia. The sugarcane industry in north-eastern Australia attracted many Japanese laborers, as did the pearling industry along the north-western coast. Mother-of-pearl shell was highly sought after in Europe to make buttons for clothing. Like the sugarcane workers, Japanese divers and ship crew were nearly all indentured—forced to work for a set period until they had repaid their debts. The work was grueling, hours were long, and the risk of injury and death was high due to decompression sickness, cyclones, and shark attacks. But the Japanese proved adept divers and eventually held the most lucrative positions among the workforce that also comprised Malays, Filipinos, Chinese, Javanese, Koepangers (Timorese), and Aboriginals.

In 1901, the Immigration Restriction Act (otherwise known as the White Australia Policy) was passed to eliminate Asian immigration to Australia. However, due to the dearth of white workers skilled or willing enough to engage in pearl-shell diving, the pearling industry was exempt.

Japanese divers were typically from impoverished villages on the Wakayama coast. Although the pay was low by Australian standards, it was many times more than what they could make at home. They signed two-year contracts and returned to Japan after they had expired. A small percentage stayed in Australia, often marrying or starting families with local women.

Although the vast majority of Japanese immigrants to Australia were men, a small number of Japanese women arrived during this period, too. The majority ended up on Thursday Island above the northernmost tip of mainland Australia, as it was a pearling hub and on the shipping route from Japan. They commonly worked at brothels frequented by Japanese clientele.

In the 1920s and ’30s, Japan became an important trading partner to Australia, becoming one of the nation’s biggest buyers of wool. Japanese textiles were also gaining popularity in Australia. This paved the way for a new wave of Japanese residents: well-educated employees of large zaibatsu firms such as Mitsui and Mitsubishi.

In the early 1940s, many Japanese residents sensed war-related turmoil and decided to return to Japan. At the time of Japan’s entry into the war, there were only 1,141 Japanese registered in Australia. About a third were divers working in the pearling ports of Broome, Darwin, and Thursday Island. The others were mainly elderly, long-term residents who had arrived before the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901. Nearly all were rounded up and interned for the duration of the war.

WWII internment

Many have heard of the internment of Japanese civilians in the United States and Canada, but few are aware that Japanese civilians were also interned in Australia during World War II. This lack of awareness could be due to the difference in numbers: there were 112,000 Japanese civilians interned in the United States, 22,000 in Canada, but only 4,301 in Australia (Nagata 1996, p.xi).

Furthermore, the Japanese civilians interned in Australia were a much more disparate group than those in North America, as only 1,141 of those interned in Australia had been living in Australia at the start of Japan’s entry into World War II (mostly working in agriculture, the pearl diving industry, and at Japanese trading firms)—the remaining 3,160 internees had been arrested in Allied-controlled countries such as the Dutch East Indies (present day West Papua in Indonesia), New Caledonia, and the New Hebrides (Vanuatu), and transported to Australia to be interned (Nagata 1996, p.xi).

Why were they interned?

It was Australian government policy to intern “enemy aliens” as they were seen as a threat to national security—in other words, they were under suspicion of acting as spies. Because of this, during World War II more than 16,000 Germans, Italians, and Japanese were interned in Australia when war broke out with those countries.

Although there were slightly fewer Japanese civilians interned than Italians or Germans, the rate of internment of Japanese was higher than any other nationality, with 98 per cent of all Japanese in Australia interned, in comparison to 31 per cent of Italians and 32 per cent of Germans (Lamidey 1974, p. 53). This was because Japanese were more conspicuous in the population, and also because “Japanese nationals are not absorbed in this country as are many Germans and Italians” (Internment Policy, War Cabinet 1941) and thus were considered more likely to become spies.

From 1942 some Japanese internees were allowed to appeal against their internment on the basis of their old age, long residence in Australia, or family considerations. However, many were discouraged from appealing due to the fact that it was the height of the war and “public feeling would be against [them]” (Bevege 1993, p. 141); they felt they would be safer in internment. In any case, of the 129 appeals that were heard in court before the Aliens Tribunal, only a handful were successful.

Most of the Japanese who were interned in Australia were interned for at least four years, from December 1941 (after the attack on Pearl Harbor) until they were repatriated to Japan in 1946.

Camp life

There were eight permanent internment camps around Australia and several more temporary camps. Japanese were mainly interned at three camps:

- Hay, New South Wales (unattached single men over the age of 16, mainly those employed as merchant seamen, including pearl divers)

- Loveday, South Australia (unattached single men over the age of 16)

- Tatura, Victoria (family groups, women, and boys under the age of 16)

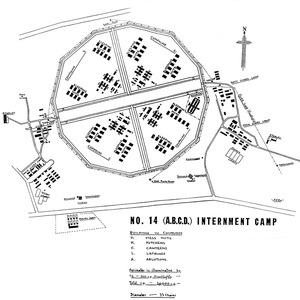

The Loveday camps (camps no. 9, 10 and 14) in the Riverland District of South Australia were the largest group of camps, with a combined capacity of 6,000.

The camps were generally divided by nationality, with Italians, Germans, and Japanese living in separate quarters. However, even among the internees there was a great diversity of backgrounds: for example, Japanese internees included those from New Caledonia, New Guinea, Japan-occupied Formosa (Taiwan), Korea, and a hundred or so Australian-born Japanese—some of whom were third-generation Australians (Nagata 1996, p.55).

The policy of internment regarding Australian-born Japanese and mixed-race Japanese was unclear: some were interned while others were exempt, depending on whether or not they showed sympathetic tendencies towards Japan (and in some cases whether they had a good relationship with their local police commander). One unfortunate 15-year-old, Jack Tolsee, was interned on the basis that he had been living with a Japanese family, even though it was later determined he did not have any Japanese blood in him (Nagata 1996, p. 57).

Click to enlarge. Map of Loveday internment camp. (Courtesy of the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources.)

Because of the diverse cultural backgrounds of the internees, tensions eventually arose, with Formosans complaining of ill-treatment by other Japanese, and they were generally excluded from camp administration and social activities (Nagata 1996, p. 186). Australian-born internees and mixed-race internees often found themselves at odds with the other Japanese because of their different beliefs and sympathies. At Loveday, a group of seven Australian-born and mixed-race Japanese became known as “The Gang” and were often involved in petty fights with the other Japanese. Because of their Australian heritage, members of The Gang became friendly with the officers and were often given special privileges, such as being invited to quiz nights organized by Australian military personnel (Nagata 1996, p. 173-176).

Each camp was self-governed, with internees required to elect their own executive committee and “mayor” (Shiobara 1995, p. 12); the elected committee reported to the Australian military officer in charge of each camp.

Work

Internees in Australia were treated according to the 1929 Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. As such, they were fed the same rations as Australian troops and could not be forced to work.

However, to alleviate boredom, many internees chose to take part in voluntary paid work at the low rate of 1 shilling a day. The type of voluntary labor ranged from growing vegetables to dyeing clothes and running a piggery. At Loveday some internees took part in a secret poppy-growing project that was so successful it eventually supplied a large portion of the morphine needed by the Australian army at the time (Australian War Memorial).

Internees were required to carry out their own chores, such as the cleaning of sleeping huts, the kitchen, toilets, and shower cubicles. Internees’ quarters were subject to a rigorous daily inspections by military personnel.

(Although internees were overall treated well by Australian authorities, separation from family members and loss of civil liberties caused great anguish: there were several suicide attempts and at least one successful suicide among the Japanese, when a New Caledonian internee swallowed glass in June 1942 and later died in a hospital [Nagata 1996, p. 159-160].)

Entertainment

Finding ways to pass the time within the bounds of camp was a constant challenge to the internees, but the Japanese proved very resourceful, using their skills to create ornamental boxes, geta (traditional clogs), baskets, smoking pipes, homemade lamps (fuelled by leftover cooking fat), and mah jong sets.

Japanese internees also put a great deal of effort into beautifying their surrounds, planting shrubs, cacti, and flowering plants (Nagata 1996, p. 161), and creating elaborate landscaped gardens with ornamental stones, ponds, and bridges. They even built small wooden Shinto shrines for worship.

Sport was a popular pastime, with Japanese internees taking part in tennis, sumo wrestling, cricket, and baseball tournaments.

At night, some camps were treated to occasional film screenings, while at other camps internees staged Kabuki, Noh, and music performances for the entertainment of their fellow internees.

Japanese internees were allowed to celebrate many traditional holidays including New Year’s Day, the Emperor’s Birthday, and National Foundation Day (Nagata 1996, p. 160).

After the war

Japanese internees boarding the ship Koei Maru in February 1946 in Port Melbourne (Australian War Memorial 125647).

Japan’s surrender on August 15, 1945 was greeted with disbelief by many internees. One former internee committed suicide while aboard the repatriation ship to Japan when he finally realized the surrender had been true (Nagata 1996, p. 199).

The Australian government adopted a policy of mandatory repatriation to Japan of all Japanese internees, unless they had been born in Australia or had an Australian or British-born wife. This caused many internees great distress, as some had been living in Australia for more than 40 years and had businesses in Australia they hoped to return to. Despite their appeals, they were nearly all forced to return to Japan by ship in 1946. The Japanese community in Australia was greatly diminished, with only 340 Japanese registered immediately following the end of the war.

The policy also adversely affected many of the New Caledonian Japanese internees who were forcibly repatriated to Japan despite living in New Caledonia for several decades. Many had families in New Caledonia that they would never see again (Tsuda 2008).

In 1988, US Congress passed legislation apologizing for the internment of Japanese civilians in the United States. The legislation acknowledged that government actions were based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership” (100th Congress, S. 1009). Surviving former internees were awarded $20,000 in reparations. No such reparations have been made to civilians interned in Australia.

In 1947, Arthur Calwell, who was chairman of the Aliens Classification and Advisory Committee in Australia during World War II, wrote:

“When passions are let loose by war it happened all too often that foreigners, whether or not of enemy origin, and even locally born persons bearing foreign names, became the object of denunciation and persecution… A good deal of avoidable human misery was caused by some of the actions taken in connection with the control of aliens.” (Lamidey 1974, p. 1)

Upon their release, many of the Australian-born and mixed-race Japanese internees were keen to return to their former lives in Australia. However, life as a Japanese descendent proved difficult, as they were subjected to racist abuse, which intensified when stories of Japan’s wartime atrocities and brutal treatment of Australian POWs emerged (Nagata 1996, p. 214). Broome local Jimmy Chi returned to his hometown to discover his house and restaurant had been burned down. Broome’s Japanese population had numbered about 300 before the war, but only nine afterwards (Nagata 1996, p. 227), further compounding his isolation. He endured years of antagonism before he eventually found work and regained acceptance within the community.

Read an interview with an internee, Mary Nakashiba >>

* This article was originally posted on the “Loveday Project: Japanese Civilians interned in Australia During WWII” website and revised for Discover Nikkei.

© 2014 Christine Piper