This year, all Canadians, especially those of us of Japanese descent, should take a special moment to meditate on what happened to our community just 70 years ago when our right to be Canadian was challenged in ways that are unimaginable for anyone born after we were “Enemy Aliens.”

On February 24, 1942 the lives of 21,000 Japanese Canadians who lived within British Columbia’s coastal 100-mile “exclusion zone” were shattered by Order-in-Council 1486. The order authorized the federal government to begin the calculated destruction of the Japanese Canadian community in B.C. Racist and opportunistic business leaders, politicians at all levels of government and the media were complicit in the crimes that our innocent families suffered through during World War Two.

Seventy years ago, when Vancouver’s Japantown on Powell Street was still thriving along with our own shops, schools, businesses, churches and baseball teams, when we were working hard to create new immigrant lives here, writer and editor Susan Aihoshi’s maternal grandparents were working at the Tairiku Nippo newspaper in Vancouver. Her paternal grandfather, Naosuke Aihoshi, was a Vancouver tailor and a widower.

Aihoshi’s new book Torn Apart: The Internment Diary of Mary Kobayashi (Scholastic) is part of a new wave of soul searching by Nikkei who did not go through the internment experience to make some sense of what their parents and grandparents went through. Works like Toronto yonsei Chris Hope’s movie Hatsumi: One Grandmother’s Journey Through the Japanese Canadian Internment and Brendan Uegama’s (Tsawwassen, B.C.) short film Henry’s Glasses and others are centered around coming to terms and making sense out of the unimaginable.

2321 Oxford Street in Vancouver was Mary's family home in Torn Apart. In real life, Susan's mother lived there until 1942. The house was later torn down along with many others on that street. An apartment building stands there today.

As the community continues to grapple and struggle for direction in 2012, when our JC centres across Canada and the survival of the institutions that define us are in serious jeopardy, these creative works are a hopeful sign that the heinous intention of Order-in-Council 1486 has not won out; that being dispossessed of our property, being labelled “Enemy Aliens”, put into internment and P.O.W. camps, “relocated” east of the Rockies and deported to Japan, in the end, has not destroy us. Yet.

Following up on my review of Susan’s first book, I wanted to get to know more about this 59-year-old sansei writer and editor who lives in Toronto with husband Roger Stevens. She makes some time for this interview while in the midst of preparing for a promotional tour in late May and early June that will take her to venues in Vancouver including Joy Kogawa House and the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre in Burnaby, B.C. on Saturday, May 26 at 3:00.

Can we begin by talking about your grandparents?

My maternal grandparents both worked at the Tairiku Nippo newspaper in Vancouver. Yoriki Iwasaki was from Okayama-ken, Midori from Toyama-ken. My Aihoshi ojiichan was from Kagoshima-ken. My paternal grandfather, Naosuke Aihoshi, was a Vancouver tailor and a widower. Both my mother’s and my father’s families were interned in New Denver. My mother’s family went to Rosebery quite soon after arriving in New Denver, perhaps because my mother’s older sister Amy Iwasaki became the first principal of the elementary school that Hide Hyodo set up there.

What did you hear about their experiences in the internment camps?

While growing up, I heard very few stories about the internment aside from brief mentions of New Denver or “the ghost towns.” I was aware that my mother and her two older sisters had been teachers, as well as aunts from the Aihoshi side of the family but it never occurred to me to ask them why!

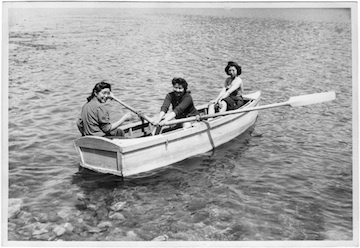

Susan's mother and her family with other members of the congregation of St. Anthony's parish in New Denver on Easter Sunday, 1944.

Why not?

When I was young, I saw my grandparents, parents and aunts and uncles in their familial roles, not as individuals who had past lives of their own. I think this is the typical ignorance of youth. For example, it was not until I was much older that I even realized one of my aunts enjoyed live theatre like I do.

The only other story I heard over the years was how my father drove trucks for the logging companies.

Any specific stories?

Nothing specific, just that the roads were snowy and icy that first bad winter. Also that the hakujin bosses liked my father’s driving—he was very careful. I learned much more from my father’s brother Barney during the research for this book! One of many stories he told me was that my dad was able to get those “I am Chinese” buttons from some Chinese girls he knew, so he and my uncle were able to go around town after curfew by sporting those buttons.

Where did they end up “resettling” after internment?

The Iwasakis and the Aihoshis came to Toronto when the government proposed that the Japanese community of B.C. move east of the Rockies. I don’t think that my Canadian-born nisei aunts and uncles or their friends seriously considered “repatriating” to Japan. As young adults, they left B.C. for Ontario before WWII was over, in most cases without their parents who came later. My mother’s oldest brother Tsutomu (Tom) Iwasaki was one of the nisei who volunteered to join a road camp in northern Ontario in April 1942, so he never did go to a B.C. internment camp.

When Susan was a young girl unaware of the evacuation, she envied her mother's and her friends' life in the B.C. interior! Here they are boating on Slocan Lake in 1943.

What kind of work did they do?

My mother worked as a maid for a wealthy Toronto family when she first came east and later became a hairdresser. Her older sister Amy also worked as a domestic for another family but left when she was accepted in the nursing program, eventually becoming a nurse. Her brother Tom got a job at the Toronto Telegram. My father and his brother worked at various factory jobs, initially in small towns outside Toronto but then in Toronto. Dad eventually found permanent work at a dry cleaning firm (Cleanol), while my uncle became a contractor largely on the basis of his work in the road camps, repairing or constructing buildings for the evacuees. My parents were married here (Toronto) and lived downtown while my Iwasaki grandparents bought a house not far from High Park. Our family was scattered throughout the city. No one lived close to each other. I guess that was the legacy of not wanting to create a Japantown here in Toronto.

What was your experience of growing up sansei like?

I grew up in Toronto’s Little Italy/Little Portugal area. My brother David and I were the only non-white children in our school and in the entire neighbourhood. I hated being singled out for the way I looked. We were usually made fun of as Chinese, too, which irked me even more. My cousin John Aihoshi told me the same story. I had no Nikkei friends. The only Japanese we knew were immediate family or my parents’ or grandparents’ friends and business acquaintances.

I never had a true sense of being a sansei or even feeling Japanese when I was young. That was also true when I became an adult. I did odori and went to Japanese school as a child but had no real connection to those things and quit before long. I was more interested in what I thought was Canadian culture—comic books and television. I enjoyed Japanese food (and still do!) but back then it was more exciting to try foods of other countries. I realize now how much I emphasized my Canadianness when I was growing up rather than accepting and celebrating my Japanese heritage. It was only this spring that I attended my first tea ceremony during Haru Matsuri at the JCCC.

What was your relationship like with your grandparents?

Since I could not speak any Japanese, other than basic phrases like “ohayo,” “konnichiwa,” “arigato,” “tadaima,” etc., there was no way of ever having any kind of in-depth conversation with my grandparents about the past.

As a writer, can you name some who have influenced you?

I have always been interested in writers and writing from all countries and cultures—British, American, European, Canadian and Japanese with no specific JC writers that have influenced me but I have read and enjoyed Joy Kogawa, Hiromi Goto and Terry Watada. I have yet to read Kerri Sakamoto.I studied English literature and creative writing at the University of Toronto and worked at Books in Canada magazine for 17 years so am widely read in Canlit but not specifically JC.

In 2002, I quit a full-time job as an editor to pursue my long-time dream of becoming a writer. I began working on a collection of fictional short stories based on my Toronto childhood in the 1950s and 60s. I eventually became a freelance editor for financial reasons but still kept writing. My former manager Hugh Brewster, an established children’s book author, suggested I might write a book on the internment for Scholastic’s Dear Canada series. I was surprised that this topic had not yet been covered but with Hugh’s help, I made contact with Scholastic and was eventually offered a contract in the fall of 2009 to write the book for 2012, in time for the 70th anniversary of the uprooting.

What was Scholastic’s interest in doing this book?

The “Dear Canada” series attempts to cover all major events in Canadian history, so it was important to include the uprooting and internment of JCs. Until I read the Dear Canada called Prisoners in the Promised Land, I had no idea that the same legislation that was enacted to uproot and intern the Japanese (the War Measures Act) had been used to do the same thing to people of Ukrainian background in WWI. That’s why it’s so important that these events are not forgotten! There are 30 books in the series now, along with teaching guides, covering the period from pre-Confederation until WWII. They have not appeared in chronological order.

What was the research and writing process like for you?

Both Susan's mother and her father's families had been sent to New Denver, a small village on the shores of Slocan Lake. Back then New Denver's population was about 300 people, so an influx of over a thousand Japanese Canadians had a dramatic effect. Today, most of them have left but the village is the location of the Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre, a national historic site.

It was one of huge self-discovery. Before this I thought I knew what had happened to the Japanese Canadian community during the period after Pearl Harbor but there was so much I was unaware of. And now I was reliving it through the eyes of my own family members. I interviewed my mother, aunts, and uncles. Initially, everyone was reluctant to talk to me but gentle probing brought forth a wealth of stories. I have a great deal of material I can use in future! Of course, I also spoke to non-family members such as my mother’s childhood hakujin friend, Margaret Lloyd who was the model for Maggie in the book, as well as her sister Ina Boxeur. I also interviewed Emiko Mori of New Denver through the help of the people at the Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre as well as Toshiko Usami, who is the family friend of a hakujin colleague of mine. They all gave me additional perspectives on what had happened.

It was a very moving experience for Susan to walk through some of the buildings where families like my own once lived.

There were many memorable occasions during my research. The one that stands out is my visit to New Denver and the Slocan Valley in the fall of 2009 and touring the Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre. The glorious weather and stunning scenery were at odds with the dismay I felt inside those shabby cabins. It was then I realized what a long way my grandparents and parents had journeyed to their new lives outside B.C.

Do you have any tips for young Nikkei who might want to interview their own family members about their internment experience?

Don’t be afraid to ask questions and be persistent. I was surprised at how my nisei aunts and uncles opened up about their past experiences now that their parents are gone. Don’t wait until it’s too late!

What is your personal opinion about the whole internment experience?

I became very angry reading about the “uprooting” and internment. Muriel Kitagawa’s book This is My Own stood out for me because finally I heard a nisei who lived through those events and was as angry as I am about what happened and rightly so. My character Mary Kobayashi expresses some of that anger, which may be an anachronism but my book is historical fiction. I don’t know if I can forgive the politicians that were so blindly prejudiced. That’s why I feel so strongly that these events should not be forgotten.

What do you have to say to those Nikkei who are just starting on their own road of self discovery?

History isn’t just what happened in the past; it’s also what we decide to remember. Take the time to ask the questions, find the stories—they will be there. You will be amazed.

I hope that Torn Apart will bring to life for all its readers a period of time in which a great social injustice took place. I hope younger members of the Japanese Canadian community will become more aware of what their elders went through during the evacuation and uprooting. And I hope it will make them proud of their Japanese heritage.

I don’t know what my grandparents would have said about this book but I hope they would have been pleased.

What has your mother said about the book?

My mother hopes that sansei, yonsei and gosei will learn from it. She also said she is very proud of me and glad that the story of what happened to the Japanese in B.C. is reaching a wider readership.

Check Susan’s website http://www.susanaihoshi.ca for more up-to-date information.

© 2012 Norm Ibuki