Read Part 9 >>

It was not until I looked at an online version of the 1944 Born Free and Equal (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/anseladams/ ) that I felt the full impact of Adams’s message. This original version includes several landscapes omitted from a 2002 reprint (Spotted Dog Press, Inc., Bishop, CA), including his majestic Winter Sunrise, The Sierra Nevada, from Lone Pine California 1944 and Mount Williamson, Sierra Nevada, from Manzanar, California (see Part 6 for more on why these were omitted). Adams included these images in the original Born Free and Equal to elevate his message and the plight of his subjects and to illustrate the source of their strength and salvation; the effect is undeniably powerful. (All 244 of the Manzanar photographs that Adams donated to the Library of Congress are also accessible on the Library of Congress Web page.)

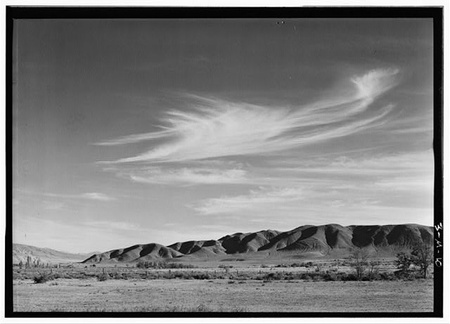

It is also hard, however, not to sense some manipulation at play. Heartfelt as Adams’s belief in the redemptive power of the gorgeous Sierra landscape, he left out an important part of the story, one that my Uncle George could not forget. Even as he described the indelible impression left by his first dawn at Manzanar, my uncle recognized that “the sweep of the searchlights atop the watchtowers” and the Sierra as a “formidable barrier to cross” were key components in this memory. Similarly shadowed is George’s description of the spectacular moment when the sun appears over the Alabama Hills, “as with a nuclear blast, drenching the entire valley in its warm golden rays,” his choice of words evoking the atrocity that ended the war, the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The Alabama Hills, lowest of the three mountain ranges that created "formidable barriers to cross" for inmates dreaming of escape. Photograph by Ansel Adams. (Photo: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.)

In Born Free and Equal , after extolling the magnificence of the natural setting at Manzanar and its uplifting effects on prisoners there, Adams agrees with the assessment of his friend, camp director Ralph Merritt, that the concentration camp was justified by “military necessity.” Adams further argues, quoting Merritt, that the forced roundup was good for the Japanese because of the assimilation that would follow when freed residents were obliged to “scatter throughout the country” instead of drawing “timorously together in the ‘Little Tokyos.’”

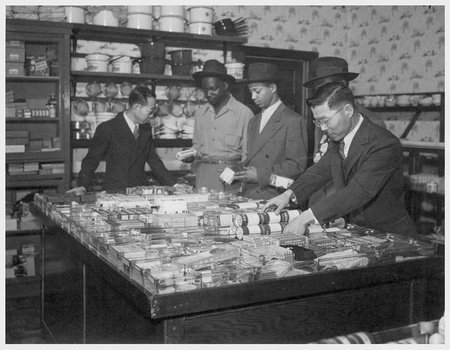

Adams defended the Japanese inmates most vigorously in the final chapter of Born Free and Equal . “The spirit of Jim Crow walks in almost every section of our land,” he wrote, pointedly noting that Americans of Germans and Italian descent had not immediately been assumed disloyal. He acknowledged the heightened racism on the West Coast and the fear of reprisal even among freed internees who decided to move to the Midwest, where anti-Japanese hostility was less pronounced. Adams raised the possibility that “thousands of formerly self-supporting citizens will remain as public wards,” and called for a “widespread campaign of education, sponsored by the government” to assist the newly freed prisoners.

Adams hoped freed inmates would be forced to assimilate instead of rawing "timorously together in the 'Little Tokyos.'" Store owner Kiichi Uyeda (right) was the first Manzanar inmate to return to Little Tokyo, Los Angeles, renamed "Bronzeville," and now home to a mostly African-American population. Photograph by Charles E. Mace. (Source: Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.)

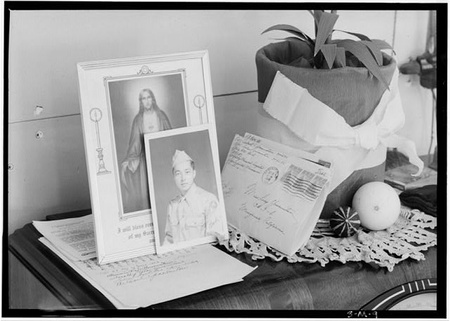

For all his deference to government and military rationale for the concentration camps, Adams could be a perceptive and understated truth teller. A single image from Born Free and Equal , Top of Radio in Yonemitsu Residence , depicts a framed image of Jesus, palms outstretched. Leaning against this picture is a portrait of the young Robert Yonemitsu, in military uniform. Next to these pictures, a stack of letters from Yonemitsu to his younger sister in camp leans against a potted lily with a crepe ribbon tied around it.

The photograph reveals a subtlety lacking in Lange’s carefully composed images of human suffering. “There is much in the details in Adams,” Graham Howe said in an interview, analyzing Top of Radio in Yonemitsu Residence . “He allows us to speculate on patriotism by including cultural signifiers, while Lange deals in a much more direct, literal way. You’ve got to work on getting meaning out of Adams.”

This poignant Manzanar photograph depicts a portrait of Jesus, a photo of Robert Yonemitsu in military uniform and his letters to his imprisoned family. Photograph by Ansel Adams. (Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

Image Preservation and Curatorial Dilemmas

Perhaps as a result of the criticism received by Born Free and Equal or to keep the highly lucrative Adams legacy free of political taint, the Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust refused to approve the republication of Born Free and Equal in 2002 by the small California press Spotted Dog. This caused much anguish for publisher Wynne Benti, who recalled the months she fought to complete the project as among the most difficult of her life. “I remember being at the UCLA book festival,” Benti told me. “People walked away and refused to buy the book because it was not approved by the trust.” In the end, Benti was forced to leave out Born Free and Equal ’s powerful nature photographs since they were not in the public domain. Adams had not included these among the Manzanar images he donated to the Library of Congress from 1965 to 1968; they had become a valuable source of income he sought to protect.

The considerable criticism of Adams’s accommodationist views makes showing his Manzanar photos problematic for some Japanese-American curators. When I approached Rosalyn Tonai, executive director of the National Japanese American Historical Society in San Francisco about possibly displaying these prints with text discussing them as both art and propaganda, Tonai welcomed the idea. It was the only way, she noted, that she would be willing to show them.

© 2011 Nancy Matsumoto