Read Part 2 >>

Why Are They Smiling?

My initial confusion about and inability to understand the Issei and Nisei attitude toward their imprisonment contributed to my fascination with the documentary photographs of Manzanar: If the Nisei and Issei would not talk about what really happened, wouldn’t photographs of the camp reveal the truth? The answer, I discovered, was “not really.”

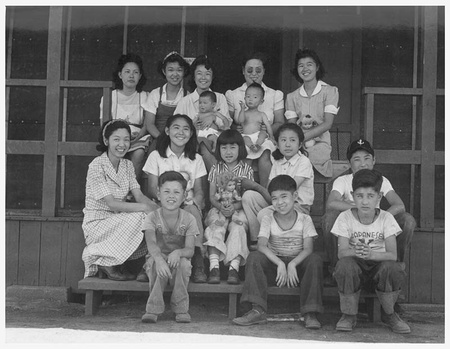

Photographs like this one by Dorothea Lange, of smiling, freshly groomed and dressed evacuee orphans and their caretakers at Manzanar belie the stark reality of their unconstitutional imprisonment. (Source: War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement Series 8: Manzanar Relocation Center)

“If we judge from the images themselves,” the historian Roger Daniels wrote of the hundreds of thousands of War Relocation Authority (WRA) photographs taken of the prison camps, “we must conclude that almost none of the photographers….seem to have had any notion that they were recording an American tragedy.” The two photographers he considered exceptions to this generalization were Dorothea Lange and Clem Albers. Lange eventually became famous for her compassionate portrayal of concentration camp prisoners, while Albers remains largely unknown to this day.

Smiles such as these, of young women unpacking after arriving at Manzanar, contributed to the confusion and anger of third- and fourth-generation Japanese Americans trying to understand the concentration camp experience. Rear: Eva (left) and Emiko Yamashita. Front: Michi Yamashita (left), and Taka Sakai. WRA caption of this Clem Albers photograph read, "Family groups are kept intact in housing." (Source: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

In her 1999 one-person show Old Man River, Cynthia Gates Fujikawa told of her attempt to reconstruct the life of her father, Jerry Fujikawa, a Manzanar inmate who later portrayed Asian caricatures in movies. Interviewing her father about his camp experience for a ninth-grade report, the playwright became frustrated at hearing only tales of basketball and social dances. A trip to the UCLA library yielded Ansel Adams’ book on Manzanar, Born Free and Equal, about which Fujikawa exclaims:

They’re smiling! The people in the pictures – they’re really smiling into the camera!

University of Wisconsin history professor Jasmine Alinder writes that the “unsettling” smiles found in so many Japanese prison camp photos are charged for several reasons: “They appear to belie the injustice of incarceration and the suffering it caused, they are reminiscent of the ugly stereotype of the grinning Oriental, and they suggest that those portrayed were entirely compliant with the government’s racist agenda.”

Photographs of smiling prisoners confound observers from Japan, too. The master Japanese photographer Eikoh Hosoe, a friend of Toyo Miyatake’s and an editor of the Japanese-language book Toyo Miyatake Behind the Camera 1923-1979, wrote:

Looking through all of these photographs, one can’t help but notice that all of the people in the pictures are smiling cheerfully. Closer examination of the sharp images in the large negatives reveals that these smiles were not just put on to pose for a picture. The people are smiling brightly from the bottoms of their hearts. Where do these smiles come from? Did these people, who had been enclosed in a strange environment, show these smiles in Toyo’s pictures alone?...Why are they smiling so brightly?...Unraveling the mystery behind these smiles may be the key to knowing Manzanar.

Alinder points out that the lack of a “clear sense of victimhood” in photographs of smiling prisoners seems to insidiously normalize a traumatic experience. For third- and fourth-generation Japanese Americans, the Sansei and Yonsei, this ambiguity in the visual record of imprisonment combined with their grandparents’ often jolly recollections results in confusion and unease, then a desire to solve “the mystery behind these smiles.”

The limited ability of photographs to convey the horror of an ongoing event was on director Claude Lanzmann’s mind when he argued that clandestine photographs of Auschwitz-Birkenau taken in 1944 should not be seen at all because they portray only a fleeting moment in time, not what really happened. Lanzmann, director of the epic 1985 documentary about the Holocaust, Shoah, explained, “Archival images are images without imagination.”

In her memoir, Kiyo’s Story, Kiyo Sato writes about leaving Poston prison camp to attend a small college in Michigan and the brave front of cheerfulness she adopted to deflect attention and fit in:

My body stiffens only when another body comes toward me. I prepare myself to smile. I’ve learned that my survival depends on it. In my days since my release from camp, I’ve learned how to cope with stares. I am a curiosity. I look at each person full square in the face and smile. Little do they know that behind those tilted lips is a twenty-year-old trying to be brave. I squelch the tiny wave of homesickness in my chest. I long to be home where I am safe.

Sato’s account of how she mustered a brave face offers insight into how the “ugly stereotype of the grinning Oriental,” as Alinder puts it, may have evolved. Only the viewer who brings his imagination, or some knowledge of the history of the concentration camps might see beyond the grin of a Japanese inmate and intuit what Sato spells out in her book. In his essay “Recollections of Heart Mountain,” Peter K. Simpson, a former U.S. Representative from Wyoming, recalled the life-changing experience of his six visits to the Wyoming Japanese concentration camp. He made one trip as a Boy Scout, to participate in a day-long jamboree with the camp’s Troop 379. He was shocked to find that the enemy aliens he feared spoke perfect English, knew the Episcopalian liturgy, tied sailor’s knots better than he did and liked football. Many years later, in his account of a visit to an exhibit of relocation pictures at UCLA, he wrote, “I was looking mostly at the faces of people in the photos to see how visibly the tragedy might have been written on them. Though I never saw it in their faces, I could see tragedy in every grain of the pictures.”

Although they are on their way to an "assembly center," these young Los Angeles women smile and wave as their train departs. Photo by Clem Albers. (Source: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

© 2011 Nancy Matsumoto