Note: Born in Sierra Madre, California in April 1923, Yosh Kuromiya and his family moved to Monrovia, where he attended grammar school, junior high and high school. He was attending Pasadena Junior College as an art major when his family was forced out of their homes and imprisoned, like other Americans of Japanese ancestry, during World War II. His family was first sent to the assembly center at the Pomona Fairgrounds, before they were imprisoned at the Heart Mountain concentration camp in Wyoming.

Draft resister Yosh Kuromiya (seated, center) was a member of the "Poster Shop Gang," designing and printing posters at the Heart Mountain concentration camp, one of ten such camps where Americans of Japanese ancestry were unjustly imprisoned during World War II. Photo: Kuromiya Family Collection

Kuromiya became one of 63 members of the Fair Play Committee, a group of Heart Mountain prisoners who resisted the draft in protest of the government’s denial of their civil rights. Along with other Fair Play Committee members, Kuromiya, then 21 years old, was arrested, tried and convicted of draft evasion.

Kuromiya was sentenced to three years in federal prison. He was released on parole after two years, and was pardoned by President Harry S. Truman in late 1947.

A retired landscape architect, Kuromiya resides in Alhambra, California with his wife, Irene. Today, he often speaks to groups and organizations about his experiences during World War II, and especially about his experience as a draft resister.

Below is the text of a speech he gave to the Greater Los Angeles Singles Chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League on May 13, 2011.

* * *

Good evening and happy Friday the 13th! If you haven’t already had your share of misfortune today, maybe you are about to, but I hope not.

I would like to thank you all, for having me here tonight. However, I must warn you that I am neither a historian, a professor, a scholar, nor even a speaker. My exposure to history is that I’ve been around for 88 years, but never seemed to make a difference. I’ve professed a few ideas during those years but never received an encouraging response, much less a degree.

As for being a scholar, I barely made it out of high school. I think they needed the space. As for public speaking, I am hard of hearing, and as you are about to discover, most people would regard it as a blessing if they could suddenly lose their hearing when they see me approaching the stand.

I wondered what would be a worthy topic to discuss with a group of Japanese Americans, and Nisei in particular, because I happen to be one.

I believe what makes us so proud of being Japanese American is our culture, or more accurately, the culture we inherited from our parents. It is perhaps our greatest asset, source of inspiration, and what defines us the most. Some may disagree because there were many occasions when it was rather uncomfortable to be one. Indeed, it seemed more of a burden being a Nisei and an ever present cross for us to bear.

The most obvious difference from white America was, of course, our physical appearance. Other children would mimic our squinty eyes and flat noses. Some would waddle about bowlegged just for laughs. Communication, including language and mannerisms, was often the source of confusion and misunderstanding. Matters of ethics, personal, social and political, while similar in principle, were often expressed and interpreted differently by the two cultures and lead to further misunderstandings. Each culture had a different history to draw from so even good intentions were often misinterpreted.

Yosh Kuromiya (top row, second from left), is pictured here with fellow Japanese American draft resisters, all dressed in prison-issued suits, on July 14, 1946, the day they were released from McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary. Kuromiya spent two years of a three-year sentence at McNeil Island. He received a full pardon from President Henry S. Truman in late 1947. Photo: Kuromiya Family Collection

We Nisei attended schools where we were expected to adopt Western values and rules of behavior, but it didn’t necessarily guarantee acceptance from our white schoolmates and in some cases, not even from the teachers. Nonetheless, many Nisei (but not me) excelled academically, due largely to the encouragement of our parents drawing on the rigid disciplinary standards of the Japanese culture. We were generally regarded as “quaint” or “quiet” since, unlike our white counterparts, we often avoided expressing ourselves publicly. Our shyness was often misinterpreted as slyness.

At home, many of us became even more Japanese, conceding to our parents’ traditional values. We worked in the family business or farm. Our Saturdays were preempted by Japanese language schools or studying the ancient cultural arts of Japan. We were caught between two worlds, each offering rich resources to be sure, but demanding sometimes conflicting commitments and priorities. We could not deny our Japanese roots and risk alienating our parents, nor could we ignore the American in us and forego our future in the land of our birth. We must somehow continue to serve two masters; one, ethnically and culturally, the other, politically and socially, into a harmonious blend of the most humane aspects that each had to offer.

However, with the outbreak of World War II between our two masters, our dilemma was further exacerbated. We Nisei, along with our Issei parents, were held by our country as guilty of harboring enemy sympathies. This, by orders of a government that had arbitrarily overlooked the basic principles our country was founded on.

Strangely, or perhaps not so strangely, due to our pre-conditioned mandate of obedience to authority, there was little protest. What little protest there was, which took on varying forms, was met with censure and ostracism by fellow prisoners out of fear for their own safety in the event of a reprisal from an already unsympathetic government.

Thus, we prisoners in the camps, in essence, became a part of the scenario of deception by acceding to the unreasonable demands of our persecutors. What appeared as an obvious injustice was in fact the failure of both “oppressor” and the “oppressed” to perceive the injustice as a form of deception. Resolution could have been realized through either party, as deception is totally powerless in itself, and only an illusion that appears as reality to those who are willing to believe in it.

Perhaps many of us “victims” did have a sub-conscious sense of guilt for our lack of confidence in constitutional principles which prevented us from speaking out too loudly. The line of demarcation between oppressor and the oppressed thereby became somewhat blurred. Many of us Nisei, in our own way, failed to uphold the principles of the U.S. Constitution. It was not just the U.S. Government.

Aiko Herzig Yoshinaga recently published a paper entitled, Words Can Lie Or Clarify: Terminology Of The World War II Incarceration Of Japanese Americans. In it she lists the many euphemisms invented by government agencies to deceive the public, including us, of the true nature of events related to the wartime imprisonment of Japanese Americans into concentration camps.

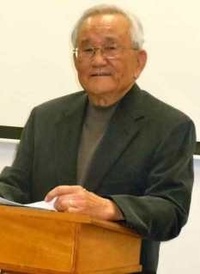

Draft resister Yosh Kuromiya speaks before the Greater Los Angeles Singles chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League, May 13, 2011. Photo: Kuromiya Family Collection

I have great admiration for Aiko for the conscientious public service she has rendered throughout the years. However, I could find no reference in her book to what seemed to be a major euphemism to justify the acceptance of questionable demands by the government with the rationalization of proving ones loyalty.

When did it become a citizen’s responsibility to prove his innocence, especially when no charges of disloyalty were ever filed nor convictions established? Was our acquiescence to government directives regarded as a form of self-incrimination?

It would seem so.

With fewer Nisei each year who lived with the many deceptions and self-deceptions, it seems this era of unreality will remain unresolved and the lies will remain a part of Japanese American history. Will the Nisei generation in our confusion forever remain a part of that lie?

History itself does not change. It is our perceptions of it that change as we peel away the layers of deceptions and self-deception to reveal the true history of Japanese Americans. But that, it seems, is a legacy we Nisei must entrust to later generations to confirm. We Nisei in our desperate search for validation from without seem to have forsaken our reality from within, and thereby our true identity as masters of our perceptions and not merely victims of our “mis-perceptions.”

Thank you.

*This article was originally published on May 19, 2011 on the Official Blog of the Manzanar Committee. Introductory note written by Gann Matsuda.

© 2011 Gann Matsuda