Read part 8 >>

In Manzanar, outside the schoolhouse walls, another educational process was occurring, this one among adults, meaningful and relevant to the situation in which they found themselves. In the barrack-apartments, in the mess halls, in conversations under the evening sky, in arguments among those of opposing views, and in meetings large and small, this education was unstructured and informal. The learners were themselves the teachers, exchanging thoughts, attempting to make sense of their situation, and debating their best course of action. As in the schools the youths attended, the theme at these encounters was democracy, and the discussions were hot and heavy.

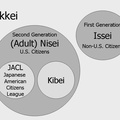

This educative process, revealed in the exchange of ideas, perspectives, and interpretations among the confined, were most clearly articulated at two large meetings: one was a meeting to organize the Manzanar Citizens’ Federation; the other was what has been referred to as the Kibei Meeting. At these meetings opposing world views confronted each other. The first world view—held by Issei, Kibei, and some Nisei—emphasized ethnic-group solidarity and Japanese notions of hierarchy in which male elders took leadership roles. At the same time, adherents to this perspective defended the civil rights of those confined and resisted the authority and power of the WRA and camp administrators. The opposing world view—held by JACLers—rejected old-world ideas, embraced Americanism, and promoted the leadership of younger citizen males. At the same time, adherents to this perspective accepted the authority and power of the WRA and camp administrators.

The first meeting of interest occurred on 28 July 1942, when JACL leaders sought to organize the Manzanar Citizens’ Federation to enable the Nisei to assume leadership in the camp. The JACLers believed that the older generation of Issei did not represent the Nisei point of view and that only Nisei, who were American citizens, could fight against discrimination and educate citizens for leadership. As speaker after speaker spoke in support of these ideas, the Nisei audience cheered heartily.

But when the floor was opened for discussion, the perspective shifted, as Kurihara challenged the previous speakers’ remarks. Before the order to leave home, job, and school, Kurihara explained, he “was 100 percent American,” but on the day the Army forced the removal of the Nikkei, “I [swore] severance of my allegiance to the United States, and became 100 percent pro-Japanese.” Speaking to the denial of their “civil rights,” he asked the Kibei and Nisei, “Why seek to remain as citizens of a country which denies us . . . rights which are guaranteed . . . by the Constitution of the United States?” Ironically, Kurihara proclaimed provocatively of being 100 percent pro-Japanese at the same time that he appealed to the U.S. Constitution.1

Kurihara went on to say that he was an American citizen who served “under fire” in France as a soldier in the U.S. Army during World War I. Despite his service to his country, he noted, he was in “this prison.” “You’re all American citizens. You’re all here, too, with me. I’ve proved my loyalty by fighting over there. Why doesn’t the government trust me?” When the JACLer Tokie Slocum responded, “We’re here because of military necessity,” Kurihara shot back. “Tokie, why are you in here? . . . Isn’t it because you’re a Jap? Isn’t it because the government doesn’t trust you?” “[We are not here] because we are unloyal. It is because we are what we are, Japs! Then, if such is the case, let us be Japs! Japs, through and through to the very marrow of our bones!” This theme, of becoming the pariah that government officials labeled the Nikkei to be, was central in Kurihara’s public pronouncements, and was echoed in statements of other Nikkei, particularly, the Issei and Kibei.2

The JACLer Togo Tanaka, who served as one of the camp’s “documentary historians,” noted that Kurihara’s remarks “drew forth spontaneous expressions of heretofore dormant feelings.” “The entire floor was electrified,” Kurihara later recalled, and “after more [of my] verbal blasting . . . the hall resounded with cheers, whistling and stamping.” In their analysis of the revolt, Arthur Hansen and David Hacker argue that this and other meetings, together with the JACLers’ petition requesting the U.S. government to draft Japanese Americans, convinced many Nisei to reject the JACL perspective. “Increasingly, the Issei-Kibei point of view was expanding into an Issei-Kibei-Nisei point of view.” What occurred with the Nisei in particular was what Jack Mezirow called a “transformation of meaning schemes,” that is, a shift in perspective and beliefs in interpreting their experiences. Tanaka himself conceded that Kurihara and others of this view eventually assumed the “leadership of Manzanar’s population.”3

The second meeting of interest occurred 11 days later, in response to a WRA directive that the Kibei were prohibited from leaving the camp on work furloughs. Upon hearing this announcement, the Kibei were incensed. As American citizens, they believed that they should have the same opportunities as other Nisei. Moreover, the contradiction in U.S. policy was not lost on the Nikkei. As Kurihara noted, when government officials needed the Kibei because of their bilingual Japanese-English abilities, they were recruited into the U.S. Army as translators and interrogators of Japanese prisoners. At the same time, because they had once lived in Japan, they were suspect and denied furloughs that would allow them to work outside the camps.4

At this point the Kibei began to speak in favor of Japan; like Kurihara, they did so as their bitterness increased in response to WRA policies. On August 8 four hundred Kibei, two-thirds of the Kibei population at Manzanar, assembled at a meeting. Also in attendance were Issei and Nisei. Speakers voiced grievances regarding medical care, school facilities, food, housing, wages, and block leaders. When a Kibei speaker declared that the Kibei were Japanese and not Americans, and that they were not loyal to the United States, his statements were greeted with loud applause. When Kurihara asserted, “If any one, any nisei, thinks he’s an American I dare him to try to walk out of this prison. This is no place for us. It’s a white man’s country,” his audience responded with “roaring applause and stamping of feet.” When the Kibei Karl Yoneda—who supported camp administrators—tried to speak, he was greeted with boos. When he said that despite “their segregation and hardships, the Japanese must still participate in the country’s war effort, the heckling was so loud that it was impossible to hear all that he said.” The Kibei meeting led the camp administrator Roy Nash to issue a bulletin that banned the use of Japanese in public meetings, which further infuriated and antagonized the Issei and Kibei, whose first language was Japanese. This meeting and its aftermath bore witness to the Nikkei’s growing sentiment of in-group solidarity that reinforced negative feelings against camp administrators and the U.S. government that they represented.5

A month after the Kibei meeting, the WRA office in Washington DC issued a directive that took political power from the Issei and gave it to the Nisei. The directive stipulated that each camp would have a council composed of elected block leaders, and only American citizens could be elected, overturning the existing organizational structure in which both Issei and Nisei were eligible to serve as block leaders. In order to execute this policy, the project director appointed a seventeen-man commission composed solely of Nisei to draft a charter for the new government. Both Issei and Kibei were excluded from the commission.6

This wresting of political power from the Issei compounded the already heightened resentment that coalesced at the recent meetings, creating “turmoil” in Manzanar. Kurihara, standing in the midst of this turmoil, challenged each of five JACLers to a “public debate.” The question would be whether the Nisei should reaffirm their “allegiance to the United States” under the existing circumstances or highlight the hypocrisy of America, reject it, and affirm their Japanese identity. Kurihara’s elocution experiences at St. Ignatius High School, coupled with the affirmation he received from his speeches at meetings, gave him confidence in his public-speaking abilities. The debate never took place, however, since all five men declined his challenge.7

The next two months witnessed growing opposition to the charter commission. At a meeting on November 25 to discuss the proposed charter for the new organizational structure, an attendee remarked to Manzanar’s chief administrator: “Look out the window and what do you see? There is barbed wire, there is a watch tower, and there is a soldier who guards us by day and night and shoots us if we break the law. Because . . . we have no self-government, I move that the damned charter be thrown out the window.” The motion was passed without dissent.8

The meetings served as forums where the adult Nikkei voiced their views and heard others’ interpretations of their forced segregation from mainstream society, of administration policies, and of actions taken by the Nikkei themselves. Discussions at these meetings and elsewhere, often intense and rancorous, led to a sobering understanding of the failings of American democracy. Their discussions led the Nikkei to reject the hypocrisy of the WRA directive to encourage them to organize a form of self-government in an institution which took away their freedom. Ultimately, they learned that they did not have to acquiesce to their situation in silence, that they could speak their mind, express their disillusionment, protest, and challenge authority, despite their position of subordination.9

Despite denouncing their American citizenship and professing their identity with Japan, it would be a mistake to label them as being “pro-Japan,” as press reports of the period did. As the Manzanar Project Attorney Robert Throckmorton noted, “[T]he primary reasons for the demonstration did not involve the question of loyalty or disloyalty. . . . The primary causes appear to be (1) those which led the people to believe that Uyeno [sic] had been unjustly arrested; and, (2) those which led them to hate Fred Tayama, other JACL leaders and certain members of the Administrative staff.” Participant-observer Togo Tanaka opined that pre-war animosities toward JACLers that were intensified in Manzanar, as well as “clashes of personality,” led to the revolt.10

These explanations do not recognize that the forced confinement itself was a primary cause of Nikkei anger and bitterness, but they do recognize the fallacy of accusing the protesters of disloyal conduct. Having been rejected by the U.S. government and most of American society because of their ancestry, Kurihara asked, “[C]ould America blame us for the change of our mind . . . [after being] ostracized and corralled like a bunch of prisoners. . . ?” While their resistance did not free them from their physical confinement, it did allow them to maintain a sense of dignity and a sense of pride in their ethno-racial identity.11

Notes:

1. Joseph Y. Kurihara, [Speeches], Unpublished typescript, 1-2, [Nov. 1945], JAERR. For names of the original organizers of the Manzanar Citizens Federation and other details of the meeting, see Karl G. Yoneda, Ganbatte: The Sixty-Year Struggle of a Kibei Worker (Asian American Studies Center, University of California Los Angeles, 1983), 135-37.

2. Togo Tanaka and Joe Masaoka, “Project Report No. 36,” p. 1, 29 July 1942, O1.78, 67/14c, JAERR, emphasis in original; Kurihara, [Speeches], 3.

3. Tanaka and Masaoka, “Project Report No. 47,” p. 257-58, 12 August 1942, O10.08, 67/14c, JAERR; Kurihara, “Autobiography,” 40; Hansen and Hacker, “The Manzanar Riot,” 131. For discussion on the clash of opposing views, see Tanaka and Masaoka, Project Report No. 45, 6 August 1942, Manzanar War Relocation Records, Collection 122, Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California Los Angeles, hereafter UCLA. Jack Mezirow, Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1991), 94; Mezirow, p. 5, defines meaning schemes as “specific knowledge, beliefs, value judgments, or feelings involved in making an interpretation.” Togo Tanaka, “An Analysis of the Manzanar Riot and Its Aftermath,” 25 January 1943, p..3, Mananar-Incident Material, Box 69, Entry 4b, RG 210, Records of the War Relocation Authority, National Archives, Washington, DC.

4. Kurihara, [Speeches], 3.

5. Information on the meeting and Kurihara’s remarks are in Tanaka and Masaoka, “Project Report No. 47,” p. 259; Tayama to Rudisill, 9 August 1942, file 323.3 Manzanar, Box 12, General Correspondence, 1942-46, Wartime Civil Control Administration, Western Defense Command, RG 338, National Archives, Washington, DC. Information on Yoneda’s remarks is in FBI report, Kurihara et al., p. 10; and Yoneda,Ganbatte, 123, 137-38. Yoneda was a Communist who supported the U.S. war effort against the “fascist” government of Japan. The ban on speaking in Japanese at meetings had come earlier, on July 4, from the WRA office in Washington, DC. At that time, Manzanar administrators chose to interpret the directive as allowing spoken Japanese, as long as the meeting included an English translation.

6. Unrau, The Evacuation and Relocation, 513.

7. Togo Tanaka, “Special Report,” 10 October 1942, pp. 2-3, microfilm reel 149, 67/14c, JAERR.

8. Quoted in Unrau, The Evacuation and Relocation, 516, from “Project Director’s Report,” Final Report, Manzanar, Vol. 1, pp. A-26-38, Entry 4b, Box 71, File, “Manzanar Final Reports,” 1946, RG 210, National Archives, Washington, DC. Similar sentiments were expressed at another meeting held on 30 November 1942. See Tanaka and Masaoka, Project Report No. 76, 1 December 1942, Manzanar War Relocation Records, Collection 122, UCLA.

9. For a sense of the rancor and heated discussions at these meetings, see Karl G. Yoneda, “Notes and Observations of ‘Kibei Meeting’ Held August 8th, 1942 at Kitchen 15—Only Japanese Spoken,” Folder 2–Manzanar Diary–1 Aug. to 30 Sept. 1942, Box 8, Karl Yoneda Papers, Collection 1592, U.S. War Relocation Records, Department of Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California Los Angeles; Yoneda, “Manzanar Citizens’ Federation—July 28, 1942,” and “Block Meeting, Block 4, July 30, 1942,” Folder 1–Manzanar Diary–1 June to 30 July 1942, Box 8, Karl Yoneda Papers.

10. Memorandum to Merritt from Throckmorton, 2 January 1943, Mananar-Incident Material, Box 69, Entry 4b, RG 210, Records of the War Relocation Authority, National Archives, Washington, DC; Togo Tanaka, “An Analysis of the Manzanar Riot and Its Aftermath,” p. 9.

11. Joseph Y. Kurihara, “Niseis and the Government of the United States,” p. 18, Unpublished typescript, [1943], JAERR.

* This essay was the History of Education Society Presidential Address delivered at the annual meeting in Philadelphia, October 2009 and published in History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 50, No.1 (January 2010).

** The definitive version is available at www.blackwell-synergy.com.

© 2010 The History of Education Society