Read part 9 >>

Value Messages and the Power of Informal Education

The foregoing reveals a continuity of values from youth through adulthood. In Kurihara’s case, he was receptive to certain values that were nurtured during his schooldays and young adulthood, values that were played out dramatically in his later adulthood. In some ways his behavior as a dissident during World War II may be seen as a radical change: from model student and young adult, to “trouble-maker” in Manzanar. Beneath the surface, however, was a continuity of values and beliefs that proved to be remarkably resilient.

The foregoing also demonstrates the power of ideas and values, and the real-life consequences for those who acted on their ideas and values. In Kurihara’s case, he had absorbed with great enthusiasm the concepts of civil rights and democracy. For this reason he saw the incarceration of innocent men, women, and children as an outrage, a violation of essential guarantees of the U.S. Constitution. He and his fellow protesters at Manzanar agreed that the incarceration was an offense that had to be challenged even during wartime, not an act to be endured.

The U.S. government’s failure to live up to its ideals disillusioned and radicalized Kurihara. He responded by rejecting his country, which had earlier rejected him. Feeling that he could no longer remain in a land that had betrayed his trust, he renounced his U.S. citizenship. His renunciation marked the end of his purposeful movement to full integration into American society. Two months after the war ended, he boarded the first postwar ship bound for Japan—a country he had not previously even visited—where he remained for the rest of his life, never returning to the United States.

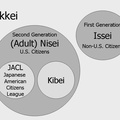

Kurihara and his fellow Nikkei in Manzanar grappled with the meaning of their confinement. They wrestled with the idea that the U.S. government, through its agencies, could summarily single out a group of people based on their ancestry, denying them their freedom and civil rights, and segregating them from the rest of society without due process.

This study serves as a reminder of the power of value messages that institutions transmit, and leads me to ask these questions.

· What values do our institutions transmit, inadvertently and unwittingly?

· What are the implications and unintended consequences of the value messages they send?

· And what happens when a society fails to live up to the values its institutions espouse?

These questions point to the importance of inquiring into the realm of informal education.

Two passages—one from an essay by Richard Storr and the other from an essay by Donald Warren—articulate the approach that I have taken in this study. In 1961, Storr further articulated the Bailyn-Cremin call to look beyond schooling for the process of education. Storr proposed an inductive approach to identifying instances where education occurred. He suggested that educational historians examine the “human experience in an effort to discover an ingredient of it that can sensibly be described as educational.” They would be “in pursuit of something that [they would not] identify fully until the end of [their] search.”] Warren picked up on these ideas. In “The Wonderful Worlds of the Education of History,” he wrote, This meant looking for “certain qualities of experience,” staying “alert for phenomena that seem to reveal places [of learning],” and “[probing] for consequences, even buried ones” to “expose . . . varied instances of processes legitimately classified as educational.”1 Like other histories of education, this study uses the inductive approach to examine the impact of formal and non-formal education. It further uses this approach to reveal the undeniable power of informal education.

(END)

Notes:

1. Richard Storr, “The Education of History: Some Impressions,” Harvard Educational Review 31:2 (Spring 1961): 1, emphasis is mine; Donald Warren, “The Wonderful Worlds of the Education of History,” American Educational History Journal 32:1 (Spring 2005), 109; Bernard Bailyn, Education in the Forming of American Society (New York: Vintage Books, 1960); Lawrence A. Cremin, The Wonderful World of Ellwood Patterson Cubberley (New York: Teachers College Press, 1965). A full discussion of the inductive approach in educational history is in Donald Warren, “History of Education in a Future Tense,” forthcoming. For an insightful critique of Bailyn’s Education in the Forming of American Society, see Milton Gaither, American Educational History Revisited (New York: Teachers College Press, 2003), in particular, pp. 91-104, 138-164. Storr was part of two working groups of historians whose efforts eventually led to the conference in which Bailyn made his address, which was later published as Education in the Forming of American Society. See Gaither, American Educational History Revisited, 158.

* This essay was the History of Education Society Presidential Address delivered at the annual meeting in Philadelphia, October 2009 and published in History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 50, No.1 (January 2010).

** The definitive version is available at www.blackwell-synergy.com.

© 2010 The History of Education Society