>> Read part 4

Nonformal Education: Instilling Patriotism

While Kurihara believed that he was getting an education of high quality at St. Ignatius School, he disliked having rocks thrown at him, being spat at, and kicked, and he had grown weary of being called “Jap.”1 In California and the West, the Japanese, like the Chinese before them, were rejected as outcasts at the same time that they were needed as laborers. Convinced that they would be better treated away from the Pacific Coast, he and a friend decided to move to Michigan. Kurihara had just completed his second year at St. Ignatius High, and he intended to continue his schooling in his new locale.

War, however, changed his plans. In April 1917, while Kurihara was still in San Francisco, Congress declared war on Germany, and on June 5th, the federal government held a national registration day. Kurihara was one of 10 million men who in a single day reported to their local registration boards in what John Chambers describes as an amazing response of “mass compliance” resulting from “propaganda, hoopla, and peer pressure.” James Montgomery Flagg’s famous Uncle Sam “I Want You” recruiting poster was symbolic of the federal government’s intensive publicity campaign to appeal to national patriotism.2

Like the other countries who participated in the war, the United States used propaganda to convince the public to support the war effort, attract men into the military, and procure money and resources. A primary medium used to reach these goals was the poster. Artists and illustrators volunteered to paint as many as 2,500 different, colorful, and eye-catching posters from which 20 million copies were made—more than the total produced by all the other nations engaged in the war.3

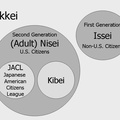

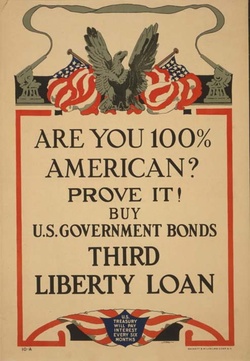

Figure 2. World War I poster, Are You 100% American? Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, WWI Posters, LC-USZC4-8075.

Posters urged men into service, called on the public to unite in the cause of liberty, to grow their own food, waste nothing, and contribute to special relief campaigns. Uncle Sam, Lady Liberty, Columbia, the American Flag, and the Statue of Liberty were frequent icons on these posters. A major theme was the need to buy liberty bonds and war savings stamps, and a large set told immigrants in particular to demonstrate their loyalty by purchasing “liberty loans.” This message to immigrants was part of a larger effort to Americanize them. By urging the purchase of liberty loans, Americanizers believed that they were encouraging thrift, the habit of saving, and the demonstration of an American identity (figure 2).4

Once in Michigan, Kurihara found a job as a bellhop at Mt. Clemens Mineral Springs. As he waited for the fall semester to begin, he became caught up in the wholesale push by the federal government to convince citizens and non-citizens alike to rally around the war effort. He later recalled that the “sound of the band, the beating of the drums” stirred in him powerful feelings of patriotism. He responded by purchasing five one-hundred-dollar Liberty Bonds (together valued at $8,000 in 2008 dollars), one for each of his five nieces and nephews. And instead of waiting to be drafted, he enlisted, becoming one of the 28 percent of draft-eligible men who volunteered.5

The U.S. entry into World War I arrived “on the heels of the Progressive Era, when middle-class reformers worked relentlessly to reorder the industrial society, socialize and morally uplift the working classes through new social welfare agencies, and restructure the urban environment with the use of scientific-management theories.” It was in this context that the War Department partnered with Progressive reformers and organizations—such as the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), the Salvation Army, the Playground Association of America, the American Social Hygiene Association, and the American Library Association—to socialize the men into wholesome activities away from the vices of drinking, gambling, and prostitution.6

Reformers saw military training as a way to bring moral and spiritual understanding to young men of different social, cultural, and economic backgrounds and create among them a common bond as Americans. The YMCA, which became a major part of camp life, built and administered clubhouses and recreation centers in the camps. The American Library Association provided books, magazines, and newspapers. The War Camp Community Service made contact with local communities to provide recreational resources for off-duty soldiers. Vaudeville acts, Bible readings, movies, and song fests were held in newly-built auditoriums. Sports and athletic events became part of the men’s spare-time activities, both in the camps and in the surrounding communities.7

Underlying all of these activities was the belief in the power of education. Basketball, volleyball, football, and other forms of organized sports would teach cooperation and team play. Bible classes would encourage moral uplift and spirituality. Debate, drama, and mass singing would develop clear thinking, good taste, and collaboration. With interest high among the enlisted men, camps also offered general education courses at the high school level, and workshops and lectures. Permeating these organized instructional efforts was the theme of citizenship training: “history became a disguise for patriotic discourse, geography an object lesson in German aggression.” Patriotism was “highlighted, trumpeted, and underlined in every conceived activity.”8

Such was the case at Camp Custer where Kurihara was sent for training. Situated three-and-a-half miles west of the little town of Battle Creek, Michigan, Camp Custer was one of 36 cantonments that were built hurriedly to meet the demands of war. The camp for the newly-created 85th Division would eventually include two thousand buildings on four miles of hills that overlooked the Kalamazoo River, and house as many as 36,000 men from Michigan and Wisconsin. Among the buildings were those of the YMCA, the Knights of Columbus, and the American Library Association, offering books, motion picture viewing, game rooms, and reading rooms. A “Liberty Theater” seated an audience of five thousand, and a large gymnasium was built from funds donated by residents of Michigan and Wisconsin.9

Notes:

1. Kurihara, Autobiography, 3.

2. Kurihara, “World War I Draft Registration Card.” A year later, with the dire situation in France demanding a much larger American presence, a second national registration day was held on 12 September 1918. With the age eligibility extended to include those 18 to 20 and 31 to 45, 13 million more men were registered. John Whiteclay Chambers, To Raise an Army: The Draft Comes to Modern America (New York: Free Press, 1987), 179-189; quotes are from page 184.

3. Walton Rawls, Wake Up, America! World War I and the American Poster (New York: Abbeville Press, 1988), 12.

4. Liberty bonds were certificates guaranteeing that the government would repay the loan with a 4 percent interest each year. A War Savings Stamp was a promissory note that a person could buy at a sum less than the amount it would be redeemed for later. For example, one could purchase a five dollar War Savings Stamp for $4.12 in January, with one cent added to the cost each month until December. The Stamp could be redeemed five years after it was issued. Rawls, Wake Up, America! 203, 221. On liberty loans and immigrants, see Thomas A. Britten, American Indians in World War I: At Home and At War (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1997), 133.

5. Kurihara, Autobiography, 5; Chambers, To Raise an Army, 200. The Detroit Free Press, 13 January 1918, printed a photo of Kurihara’s five nieces and nephews with this caption: Joseph Y. Kurihara . . . is the sort of patriot who believes that actions speak louder than words. . . . Kurihara is now at Camp Custer training with others of the selective army. Almost the last thing he did before donning a uniform was to purchase a Liberty bond for each of five little nieces and nephews. . . .” My thanks go to Henry Fujita, Kurihara’s grandnephew, for giving me a copy of the newspaper clipping. Five hundred dollars in October 1917 was equivalent in April 2008 to $7,963. See Tom V. Savage and David G. Armstrong, “Were Things Really So Cheap in the ‘Good Old Days’? Using Index Numbers to Determine the Meaning of Historical Prices,” The Social Studies (July/Aug. 1992): 155-59; and InflationData.com, “Historical Consumer Price Index.”

6. Nancy Gentile Ford, Americans All! Foreign-born Soldiers in World War I (College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2001), 9-12, 88-111, quote is from p. 137. Half a million immigrants and thousands of sons of immigrants were drafted into the U.S. Army.

7. Penn Borden, Civilian Indoctrination of the Military: World War I and Future Implications for the Military-Industrial Complex (New York: Greenwood Press, 1989), 97-99, 120-27.

8. Borden, Civilian Indoctrination of the Military, 129-31.

9. The War Department created the 85th Division soon after the United States entered the war. Camp Custer: A University of Democracy (Battle Creek, Michigan: Atkins and Jones, 1918), 1-4; Edward M. Barry, ed., Doings of Battery B: Humorous Happenings and Striking Situations and Experiences of Its Members (Grand Rapids, MI: Dean-Hicks, 1920), 12; “Splendid Gymnasium for Custer Which Gifts of Michigan and Wisconsin Citizens Made Possible,” Detroit News, 11 November 1917.

* This essay was the History of Education Society Presidential Address delivered at the annual meeting in Philadelphia, October 2009 and published in History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 50, No.1 (January 2010).

** The definitive version is available at www.blackwell-synergy.com.

© 2010 The History of Education Society