On a cool, crisp winter afternoon in a California desert, at the foot of the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, a crowd of more than two thousand people gathered. Some were curious; more were angry. Before all of them, standing on an oil tank with a microphone and loudspeaker, forty-seven-year-old Joseph Y. Kurihara shouted angry words of defiance. Referring to the generally despised Fred Tayama who was assaulted the night before, Kurihara bellowed, “Why permit that sneak to pollute the air we breathe? . . . Let’s kill him and feed him to the roving coyotes! . . . If the Administration refuses to listen to our demand, let us proceed with him and exterminate all other informers in this camp.”1

It was December 6, 1942, a year after the United States had declared war on Japan. The place was Manzanar, one of ten camps of the War Relocation Authority in which Nikkei2—ethnic Japanese—were forced to live during the war. The events that followed the mass meeting escalated into expressions of angry defiance: rock throwing, singing of Japanese songs, and shouts of contempt. At 9 PM that night, soldiers threw tear gas grenades into a massive crowd of protestors, and two soldiers who had been confronting the protestors for some time, fired into the crowd without orders to do so, killing two young men and injuring ten others.

This essay uses the speaker on that December afternoon as the avenue through which it examines the nature and role of education. The essay explores the educational thrust in three of its manifestations. The first is formal: This was Kurihara’s Catholic schooling. The second is the non-formal3 yet organized and purposeful transmission of ideas and values: This was the U.S. government’s push during the First World War to instill patriotism into its citizens and to Americanize enlisted men who were immigrants and children of immigrants. The third is informal yet meaningful: This was the education of adult Nikkei who were confined against their will in Manzanar. What they learned emerged from the intersection of policy directives, events, and discussions that took place in the camp. While this third form of education—occurring spontaneously and unsystematically—can be overlooked all too easily, it has been a powerful dimension in the educative process.

Kurihara, who has been an oft-mentioned (but unstudied) figure in the literature on the incarceration of Japanese Americans, is an appropriate vehicle for my project because he came to represent a significant viewpoint of the adult Nikkei population at Manzanar, wrote about his youth and adult experiences, and expressed his thoughts and emotions frequently and openly. Moreover, in illuminating the intersection of education, race, religion, and nationality, his story provides insights into education and its consequences.4

The ideas and values that Kurihara acquired and nurtured as a Catholic school student and as a civilian and soldier during World War I dominated his outlook and collided with the reality of the mass removal and incarceration of Pacific Coast Nikkei during World War II. In Manzanar he participated in meetings and discussions that challenged inmates’ views and perspectives. The particulars of the three educational experiences—formal, non-formal, and informal—demonstrate how institutions convey powerful value messages, intentionally and unintentionally, sometimes with positive results, other times with disappointing and even tragic consequences.

As the foregoing indicates, this essay pursues two related lines of inquiry. One explores the role of value messages in education; the other considers the significance of informal education vis-à-vis that of formal and non-formal education.

NOTES:

1. Joseph Y. Kurihara, “Murder in Camp Manzanar,” 16 April 1943, unpublished typescript, in author’s possession, pp. 2-3. Another copy with a different font is in the Japanese American Evacuation and Relocation Records (hereafter JAERR), O8.10, 67/14c, The Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley. Weather and climate conditions are given in Karl Lillquist, Imprisoned in the Desert: The Geography of World War II-Era, Japanese American Relocation Centers in the Western United States, A Research Project Funded by the Washington State OSPI, September 2007, p. 337, www.cwu.edu/~geograph/faculty/lillquist/ja_relocation_cover.html (accessed 10 June 2008).

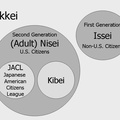

2. Nikkei: “Ni” refers to Nippon (Japan) and “kei” refers to genetic lineage. Nikkei refers to anyone of Japanese ancestry who lives outside Japan. Issei: “I” means first; “sei” means generation. Issei refers to the immigrant generation. Nisei: “Ni” means second. Nisei refers to the immigrants’ children, who were born in the United States and were therefore U.S. citizens. Kibei: “Ki” means return; “bei” means America (Beikoku). Kibei refers to those Nisei who spent part of their young lives in Japan and who later returned to the United States.

3. Lawrence A. Cremin, Public Education (New York: Basic Books), 21, 22, 27, discusses forms of non-formal education.

4. Although Kurihara’s name often appears in the literature on the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, I have not seen any in-depth study—other than my own—of his life and of his role in Manzanar.

*Author's Note:

This essay was the History of Education Society Presidential Address delivered at the annual meeting in Philadelphia, October 2009 and published in History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 50, No.1 (January 2010). I would like to thank the following people for their helpful comments and encouragement on drafts of this essay: Donald Warren, Patricia Alvarez, Roger Daniels, Karen Graves, Arthur Hansen, Dwight Hoover, Father Michael Kotlanger, Idus Newby, Warren Nishimoto, Anne Marie Ryan, and colleagues at the College of Education, University of Hawaii: Baoyan Chun, Ernestine Enomoto, David Ericson, Marsha Ninomiya, Gay Reed, and Hannah Tavares. Wayne Urban’s, ‘‘History of Education: A Southern Exposure,’’ History of Education Quarterly 21, 2 (1981): 135–45, is an essay that remains with me decades after reading it. In it, Urban not only sought to stimulate educational research outside the Northeast, but also encouraged a study of education beyond schooling.

*The definitive version is available at www.blackwell-synergy.com.

© 2010 The History of Education Society