Read Part 14 >>

In Moving Images: Photography and the Japanese American Incarceration (University of Illinois Press, 2009), Jasmine Alinder described how the U.S. military and government used photography as a tool of power and control over Japanese Americans during World War II:

The struggle over photography figured in nearly every aspect of the incarceration. The military criminalized Japanese Americans through identity photographs and prohibited cameras in the concentration camps. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI began conducting raids of Japanese American homes, and many Japanese Americans destroyed artifacts, including family photographs, that might have been construed as evidence of a link to Japan. The government hired photographers to make an extensive record of the forced removal and incarceration, and forbade Japanese Americans from documenting photographically the conditions of the camps or any aspect of their lives.

Under these circumstances, to photograph, especially covertly, with a camera made of smuggled and scavenged parts, was an act of subversion. How Miyatake managed to do this is one of the great stories of the World War II Japanese American concentration camps.

By coincidence, the WRA contract to supply hardware to the prison camp was awarded to a company that had been a client of Miyatake’s. Not only had Miyatake done work for this store, he had done his client a large favor in the mid-’20s by helping set up the store’s in-house photo department, even though it meant a loss of business for him. Miyatake was pleased to find that the same man he had helped many years before now paid a business call to Manzanar once a month. “I know it’s hard to believe that a thing like that could happen!” Archie told me still amazed by the coincidence.

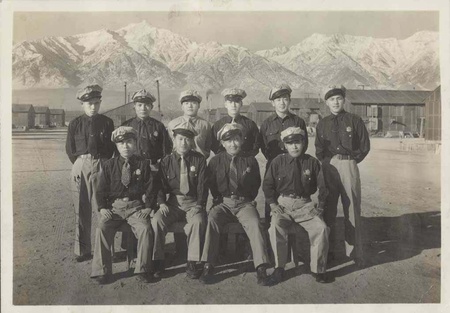

The two men set up a covert delivery system to provide Miyatake with photographic supplies he ordered from another old friend, a vendor to professional photographers. Any time the salesman came to Manzanar, he discreetly carried with him Miyatake’s order, recalled Archie. “If it was small enough, he’d leave it in his jacket pocket and tell my father, ‘My coat is hanging in the hallway of the administration building.’” Miyatake then would ask one of the concentration camp police officers he had befriended (in a surreal twist, all camp law enforcement officers except the chief were prisoners themselves) to retrieve the items. “Then there were items that were so big the salesman couldn’t put them in his jacket pocket: film developers, chemicals and papers,” Archie said. “He told my father the license number and color of his car, and he would leave the supplies in his trunk, with the trunk cover ajar.” Again, Miyatake would ask his police contact to pick up the goods. As a well-known and popular figure in the prison camp, getting help in these small subversions of authority was not difficult for Miyatake. “The policeman was more than happy to do it for my father,” said Archie. “He knew quite a few of them.”

The policemen/prisoners of Manzanar, some of whom helped Miyatake obtain the photographic equipment he needed. Photograph by Toyo Miyatake. (Gift of Hiroshi Sato, Japanese American National Museum [96.317.2])

For six months or so, Miyatake surreptitiously photographed early in the morning, or at mealtimes, when few people wandered the concentration camp, avoiding times when the MPs conducted jeep patrols. He had been following this routine for less than a year, however, when the need for an official prison camp photographer became apparent. Prisoners wanted photos to commemorate marriages and document sanctioned departures for work or school. Army volunteers wanted photos taken before they left for military service.

Manzanar project director Ralph Merritt was aware of this need when Miyatake approached him about serving as official camp photographer. Since no inmates were allowed cameras, the compromise the two reached was that Miyatake could set up the shot but could not trip the shutter. The final click would have to be the job of a white person. For a time, a young photography school graduate Merritt recruited from Los Angeles did the job. Every night this assistant removed the camera’s lens and took it home. Miyatake relied on his own wooden camera until the assistant, despite wartime shortages, foraged one from war-depleted Los Angeles. Miyatake made do by purchasing from his Los Angeles supplier the few film supplies his budget allowed.

One evening, Archie recalled, Miyatake’s last assignment of the day was photographing a large outdoor group of 200 people, whom Miyatake had painstakingly lined up. In his haste to head home, Miyatake’s assistant removed the lens from the camera before the film had been extracted, ruining the exposures. Miyatake was livid. Shortly thereafter, the assistant quit. Merritt, aware of the absurdity of the situation, came up with a new plan. He hired another non-Japanese, the wife of a prison camp employee, to simply sit with Miyatake in the studio. The photographer was now allowed to trip the shutter, and gained better control of his work, albeit still under the watch of a Caucasian. A series of four or five women briefly held the job but none could stand the excruciating boredom.

“Mr. Merritt was getting pretty tired of finding new people,” said Archie, “and by that time he and my father had become pretty good friends. He told my father, “‘Well, you know, Toyo, I can’t see anything going on the left side of me.’ My father caught on right away. Everything that happened from then on happened on the left side of Ralph Merritt so he couldn’t see what was going on.”

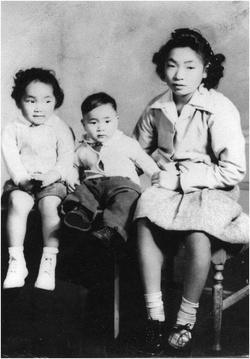

My Uncle Jim, one of the more than 500 babies born in Manzanar, seated between my Aunts Grace (left) and Mae (right), in a portrait taken by Toyo Miyatake at Manzanar. (Source: family collection.)

Now supplied with an ID card as the official concentration camp photographer, Miyatake sent for all the photographic equipment he had stored in Los Angeles. By 1943, eight months after his inauspicious arrival at Manzanar, Miyatake could at last freely take pictures on his own without supervision. His studio was considered part of the internee-run Manzanar Consumer Cooperative, which set up and owned all community businesses, including a canteen and department store, with all profits distributed among resident members. Among the portraits he shot were several of my family members. My uncle Jim was among the 541 babies born at Manzanar, and in my possession is a photograph Miyatake took of Uncle Jim and his two older sisters, my Aunts Grace and Mae.

Because of the shortage of film and other photographic supplies, Archie remembered that Miyatake had to limit photographic sessions to about two customers per residential “block” every day. The prison comprised 36 blocks, each block consisting of 15 barracks and a mess hall. Toyo also learned to take the minimum number of shots required to satisfy his customers. Instead of making up to a dozen exposures in order to get one good picture, he took only about two shots per person. For this work, Miyatake earned $19 a month, the highest possible wage for a prisoner. As his apprentice, Archie earned $12 a month.

The respect that Merritt and Miyatake developed for each other, may have been facilitated by the fact that the concentration camp director’s friends, Edward Weston and Ansel Adams, spoke favorably of Miyatake. Merritt, who was 59 when he assumed his Manzanar post, had amassed a distinguished record in public service and was liked by the Japanese immigrant community. He served as California administrator for Herbert Hoover’s federal food administration program during World War I, as president and managing director of Sun Maid Raisin Growers, and was dubbed the “czar of the rice industry” for his role in solving agricultural problems. He visited Japan to represent the agriculture industry, and, said Archie, “knew a lot of Japanese people and understood the Japanese people.”

Yet despite winning the respect of many inmates, there was never any question that Merritt was their overseer. In Moving Images, Alinder notes that in an editorial in the ironically named Manzanar Free Press, the concentration camp’s newspaper, Merritt scolded his charges for indirectly causing their imprisonment by “crowding into the seven southern counties of California.” The prison director warned the soon-to-be-released inmates not to “create another Japanese problem” by trying to return there during a housing shortage. In no uncertain terms, he made it clear that the Japanese would not be welcomed to their previous towns. That Merritt is most often remembered by the Japanese inmates as a benevolent figure and as their champion suggests how much prejudice the prisoners had internalized.

© 2011 Nancy Matsumoto