Parents and children slowly began to gather in the upstairs foyer of the Japanese American National Museum on Saturday, June 12 to await the arrival of Maya Soetoro-Ng, scheduled to read from her upcoming children’s book, Ladder to the Moon .

Guests streamed in and out of the museum all day for a program full of events sponsored by the Target Family Free Saturday program in conjunction with the Mixed Roots Film Festival. Other events included a demonstration on how to work with naturally curly hair and an urban dance performance by L.A. dance group Culture Shock. Related organizations like Multiracial Americans of Southern California (MASC) held informational booths downstairs, selling t-shirts to eager passersby.

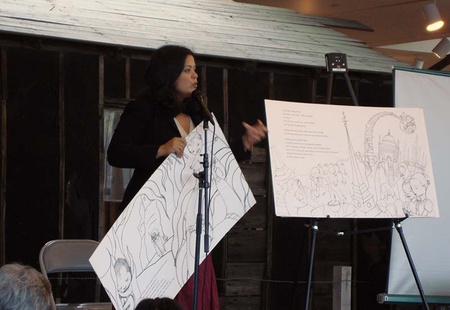

Anchoring the program were Soetoro-Ng’s reading; Kip Fulbeck’s photography exhibit, “Mixed,” made up of a series of photos of multiracial children; and a panel discussion between Soetoro-Ng and Fulbeck, moderated by actress Amy Hill.

As the hour approached for Soetoro-Ng’s reading, families made their way upstairs, their arms full of swag and craft projects. From the outset, the scene appeared to be just another ordinary family event: sure, museum-goers and staff alike felt a little dizzy knowing they’d soon be sitting just a few yards from Soetoro-Ng, author and educator known best by the public for her (in her own words) “prominent” brother, President Barack Obama. But star stricken or not, the gathering crowd continued its business as usual. Frazzled parents with overloaded tote bags and new purchases from the museum’s gift shop herded their kids toward empty seats as brothers in matching Lakers gear kicked each other absently in the shins to pass the time.

Beneath the quotidian rhythm of the crowd, however, stirred something remarkable.

To my right, a dark-haired woman maneuvered a stroller through the crowd, a pale, straw-blonde baby in her arms. Nearby, a middle-aged couple sat side-by-side smiling proudly, she with a flower in her hair, the words “100% Hapa” printed across her shirt.

Across the aisle in a hot pink shirt, a girl with a dark complexion and curly yellow hair turned toward a friend. “I could really go for some ramen,” she hinted, sliding toward the front of her seat in hungry protest.

In her lap lay a piece of paper bearing the title “My Special Family” and featuring smiling, gingerbread-shaped, construction paper people in shades of brown and beige.

It’s 2010 in downtown Los Angeles; for us, diversity is a part of everyday life, and though we may still do the occasional double-take when we see someone whose ethnicity we can’t place, mixed families are hardly cause for shock.

In the Years since Loving

The Census Bureau estimates that between 2006 and 2008, reported multiracial individuals made up more than 3% of the population of L.A. County (equivalent to more than one third the size of the county’s black population), and in 2009 this group became the fastest growing demographic in the country. Still others of mixed parentage are not included in this percentage, choosing to indicate only one race on the Census instead of two or more, whether due to personal preference or to a “one-drop” consciousness left over from the segregation era.

Important developments in the past decade, like the decision to allow individuals to identify with more than one race on the Census and, of course, the election of our first minority president, have led Americans to throw phrases like “colorblind” and “post racial” into the melting pot of our country’s racial mythology. In this climate, it’s easy to forget that less than half a century ago, anti-miscegenation laws still existed in this country, declared unconstitutional in the 1967 Supreme Court case, Loving v. Virginia.

In the years since, the June 12 anniversary of the Loving decision has become something of a holiday for multiracial families and supporters of all races to celebrate love and the freedom to share it across racial boundaries; whether or not they knew about the holiday, more than one thousand people spent this year’s Loving Day at the Japanese American National Museum.

While kids at the museum scanned their Amy Hodgepodge books, following the adventures of its cool multiracial protagonist, many of the older visitors were of an age group that could vividly remember the stigma attached to being minorities, let alone mixed, when they were children.

Circumstances have changed dramatically for people of mixed heritage in the United States over the past four decades, each successive generation able to grow up in a world that is a little more accepting and receptive than it was for the last. Still, parents hope to ensure that their children will be able to grow up feeling comfortable in their own skin with the knowledge that they are no less deserving of happiness and equal treatment than anyone else.

“Growing up,” jokes Fulbeck during the Conversations portion of the evening, “my only role model was Spock: half human, half Vulcan. I watched [him on Star Trek] and I was like, ‘Yeah, I get it.’” As the parent of a multiracial child, he expressed hope that his son Jack would be able to have more multiracial people around to identify with than he did.

Children, the next generation, seemed to be the theme of Saturday’s gathering: adults both young and old attempting to instill in them strength, confidence, and most of all, a strong sense of self. Nobody articulated this sentiment quite like Maya Soetoro-Ng.

“You can go anywhere as long as you’re respectful.”

Soetoro-Ng’s children’s book, Ladder to the Moon , came about as the author’s way of introducing her six-year-old daughter Suhaila to her deceased grandmother (Soetoro-Ng and President Barack Obama’s mother). Suhaila is the heroine of the story, which opens on a scene in which her mother (Soetoro-Ng in illustrated form) tells her that she has her grandmother’s hands. I wonder what else I got from her , Suhaila wonders. Just then, she sees a ladder extending to the moon, with her grandmother at the bottom, and so a magical adventure begins…

Soetoro-Ng’s mother passed away in 1995, almost a full decade before Suhalia’s birth. This fact still saddens the author, who would have loved for her mother to meet Suhaila and her younger sister Savita and, she says, “teach them their own power.” This is exactly what her mother did for Soetoro-Ng as she was growing up, half white and half Indonesian, all over the world, forming her own identity under the influence of mainland, Hawaiian, and Indonesian cultures.

Throughout her life, her mother served as a “tether,” a safe space in which she could always have a home. “She told me… that I had been given a gift of belonging to more than one world, that I had a flexibility that she never had, an ability to shape-shift and move through doors or fences that for her were obstructions,” writes Soetoro-Ng in her foreword to Fulbeck’s book, Mixed .

As a result, Soetoro-Ng has grown into a woman who radiates strength. Her voice is deep and soothing, and she speaks to her audience in poetic language that penetrates like mint tea or the touch of a mother’s hand on the forehead. For a multiracial person, she says, exploring different parts of one’s heritage is important simply because it “could lead to finding something you love… whether it’s a corner the size of your elbow or the size of your calf.”

For her, this took the form of seeping in not only the America of her mother and the Indonesia of her father, but the other cultures that “claimed” her along the way. Because of the ethnic ambiguity of her features, she says, “people are always telling me I look like their niece, or their friend’s niece.” There’s a sense of implied trust that comes with such a statement. “If you look like someone’s niece,” she continues, “you can let them know from early on that you’re friend, not foe... You can go anywhere if you are respectful.”

During her college years at Barnard in New York, her dark hair and eyes led her to be often confused for Puerto Rican. Maybe because of this initial mistake, she began to explore Latin American literature, dance, and music, falling in love with that world and coming to identify in a way with its people. And years later, married to a Malaysian Chinese Canadian man, she began to find another home in him and their children, and in their “Asianness.”

Despite the tendency of many to want to classify others in terms of discrete, additive categories that leave little room for individuality (“an Asian American woman,” “a black man,” etc.), Soetoro-Ng maintains that race, and identity in general, is organic and flexible. Problems between people occur not because of diversity, but because of narrow-mindedness and a lack of empathy. The more parents can help to cuitivate flexibility and understanding into their young children, multiracial or otherwise, the more equipped they will be to affect positive change in the world.

Ladder to the Moon is one example of Soetoro-Ng’s own legacy of stories that she has begun passing down to her daughters. “Umbilical stories,” stories that connect an individual to their family history and to the world, are irreplaceable in the development of a sense of self. With that in mind, “I say Indonesian prayers to [my daughters] at night,” she says. As a mother, she can only offer this foundation to her children as well as her unconditional love, knowing that they will make their own decisions as they mature and hoping they realize they will have her support whatever their choices may be.

Soetoro-Ng talks little about her brother throughout the day’s programs, but toward the end of Conversations, she tells the story of her family’s colorful gathering on the night of the inauguration, people of all races coming together simply as a family. As the multiracial part of the population grows, more and more families will come to resemble hers, she says with a smile.

As she tells this story, I can’t help but think of the crowd of families at the museum on that day. And then I think of my own family at my Nisei great aunt’s Wakayama Kenjin-kai (prefectural club) gatherings. Though the reunions are mainly for the elderly, their Japanese faces shielded by practical baseball caps or visors and corrective lenses, every year the families of this original group grow in both size and diversity. Take just my immediate family. There’s my mom, the daughter of a distant cousin in Japan; my dad, the tall white guy with the curly hair who speaks some Japanese and a bit more French; and my two brothers and I with fair complexions, whose features look vaguely Asian in certain lighting. Curry and shepherd’s pie are our soul foods; Momotaro and the legend of Bigfoot some of our umbilical stories.

With Obama in the White House and artists like Kip Fulbeck in galleries, families like ours are becoming more common—but more than that, they’re becoming better represented through community initiatives, stories, the Census (albeit problematically), and even graphic t-shirts.

What’s more, through technology, we’re all more connected to different worlds than ever before: as Soetoro-Ng cites a quote she once heard, “by virtue of our interactions, none of us is pure.” Though fear and othering still exist, exposure to new ways of life may lead to what Soetoro-Ng hopes will be a bright future for her daughters and others of their generation, marked by “a move toward cohesion and collaboration… toward empathy rather than tolerance.”

© 2010 Mia Nakaji Monnier