By day Yoshitake Kamiya worked in the fields of Okinawa, Japan's southernmost prefecture. By night he performed traditional Okinawan dances and acted in plays with Taishin Za, a famous local theater group. For twenty years, between 1968 and 1988, he also traveled the world as an official member of Kumi Odori (Okinawan-style opera with elements of singing, dancing, and acting), introducing Okinawan culture to North Africa, the former Soviet Union, Europe, and even New York.

Kamiya also introduced the art form, distinctly different from that of mainland Japan, to his niece, Junko Fisher (nee Nagahama), who began dance lessons when she was five years old. Fisher grew up watching her uncle Yoshitake's performances in Okinawa and was inspired by the beauty and pageantry of the shows. The costumes, choreography, and the sense of history impressed her so much that she made it her goal to follow in her uncle's footsteps. She soaked up as much knowledge about all aspects of Okinawan dance as she could and studied at the same school as her uncle. Today, Fisher is a performer and teacher of traditional Okinawan dance right here in New York.

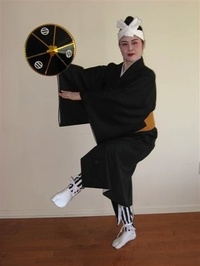

In addition to offering private instruction, Fisher performs at several festivals each year, including the Long Island Cherry Blossom Festival and the White Plains Cherry Blossom Festival. She also conducts workshops in the area. During the workshop, Fisher will perform classical and folk dances, demonstrate the sanshin (a three-stringed instrument associated with almost all of Okinawan dance), and explain the meanings of the costumes and hand gestures.

Discussing Okinawan dance with Fisher is like receiving a history lesson. To understand Okinawan dance, it's important to start at the very beginning. "Every time we explain a style of dance," Fisher says, "we have to explain how it developed, and – this is very important – which station the Ryukyu Kingdom was at the time."

Perhaps best known for its unfortunate role during World War II and for the military bases that have been present ever since, Okinawa was once a nation called the Ryukyu Kingdom. The group of islands had long had a trade relationship with China, with China as the lord and the Ryukyu Kingdom as its subject. After the death of a Ryukyuan king, the Chinese Emperor appointed a new king and sent envoys known as Kansen (Crown Ships) to Okinawa for coronation ceremonies. These were elaborate affairs that involved the funeral of the late king, the induction of the new king, and banquets to entertain the envoys.

Because of these banquets, the royal government of the Ryukyu Kingdom established the position of Odori Bugyo, a magistrate who organized musical, dancing, and dramatic performances. This was the birth of Ryukyuan performing arts. The dances performed at the coronation ceremonies were called Kansen Odori, or Crown Ship Dances. Nowadays they are referred to as Classical Dance or, more commonly, Court Dance. There are four types of classical dances: Old Men's, Young Men's, Boys', and Women's (known as the "flower of Okinawan dance").

In 1872 the Meiji government of Japan dismantled the Ryukyu Kingdom and created Okinawa Prefecture seven years later. The Ryukyuan-Chinese trade relationship was absorbed into the Japanese system, effectively ending the ceremonial trips by Chinese envoys. Doing this meant the dancers and musicians who performed at these ceremonies were out of work. As a result, they went to the local theaters and created entertainment for the common people. These dances are known as Zo Odori, or Popular Dances.

After the devastation of the Battle of Okinawa during World War II, the Okinawans needed to re-establish their performing arts. Performers started their own schools, including Nozo Miyagi, Grand Master of the Miyagi Ryu Nosho Kai Ryukyu Dance and Music School, where both Fisher and her uncle studied.

"Performing arts is a record of the history of Okinawa," says Fisher. "Dance is Okinawan history . . . Performing arts is [Okinawans'] power." As the political climate changed in Okinawa, so did the style of performances.

In her own performances and workshops, Fisher brings together all of these styles. Fisher meticulously researches each dance, making sure the makeup, costumes, and props are exactly as they were hundreds of years ago. She is passionate about her Okinawan heritage and proud that she is from Yomitan village, the first Ryukyuan village to send a trade ship to China in 1378. Fisher is equally proud that Kumi Odori, of which her uncle Yoshitake was a member, was designated an Important Intangible Cultural Asset by the Japanese government in 1972. Last year, Okinawan Classical and Zo Dances were also given that distinction.

After studying traditional Japanese dance in Tokyo during college, Fisher returned to her Okinawan roots to promote and preserve these important cultural assets and to teach the dances of the Miyagi Ryu school. It is Fisher's goal to teach people that there is so much more to Okinawa than military bases. "It bothers me, actually," Fisher says with a laugh, but she is serious when it comes to Okinawan dance.

"My purpose to do this is because Okinawan performing arts is so versatile, but a lot of people don't know about it," she says. "A lot of people know about the bases, but I'd rather introduce rich culture, history, and not the war."

*This article was originally published in exarminer.com on June 14, 2010.

© 2010 Susan Hamaker