If there’s one thing I’ve learned after 30 years of writing, it’s this: Words matter.

Words, and how they are used, have the power to uplift, soar through the sky and change the world, and the people in it.

“I have a dream,” said Dr. Martin Luther King.

Who can ever forget those words?

But words, used in other ways, also have enormous power to hurt, kill and send people to the depths of despair.

Adolph Hitler knew the power of his words.

It matters how we use them.

As Japanese Americans, key words were used against us before and during World War II that changed our lives forever. Some of them are painful. Here are just a few:

“Yellow Peril.” “Good for nothing.” “Jap Hunting License. No limit.”

Then, the forced removal of our community happened, and creative words were used like “Non-Alien” (referring to American citizens, the Nisei), and “Assembly Center” (temporary camp) and “Relocation Center” (permanent camp).

And then, in early 1943, our war-time leaders came up with more words, this time in the form of two confusing and ill-worded questions: The infamous “loyalty oath” questions #27 and #28:

Question 27

Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty wherever ordered?

Question 28

Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any and all attacks by foreign or domestic forces and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese Emperor or any other foreign government, power, or organization?

These were the words that were used to force Japanese Americans, age 17 and above, to answer either “Yes-Yes,” or “No-No.” But it’s safe to say that these words, in the context of where they were, had a devastating effect on our community that is still felt to this day. Friendships ended. Lovers split. Families were torn apart. A community was fractured.

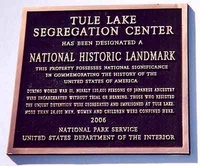

In 2006, the Tule Lake Segregation Center was designated as a National Historic Landmark by the National Park Service. This plaque was on display during the dedication ceremony for the Tule Lake National Monument.

A “Yes-Yes” answer meant that you were “loyal” to the United States. Anything other than that was considered “No-No,” and that individual was branded “disloyal” and sent along with over 12,000 others to what became the Tule Lake Segregation Center for disloyal Japanese Americans.

Tule Lake. Two words, when mentioned in our community, conjure up all kinds of emotions, usually negative.

“Oh, that was the trouble-maker camp.”

“You’re one of those disloyals.”

In other words, Tule Lake equals: The “bad” Japanese Americans.

“Trouble-maker,” “disloyal,” “bad people”—these are the words that have haunted those who were incarcerated and segregated at Tule Lake back then, and have followed them for 63 years since they left.

I have just returned from the 17th Tule Lake Pilgrimage held over the Fourth of July weekend at the actual Tule Lake camp site, and I listened to the words and stories of people who were there, including my mother, father and aunt.

Dedication Ceremony: Held on Friday, July 3, 2009, over 500 people gathered in front of the Tule Lake jail to celebrate Tule Lake being named a National Monument by the National Parks Service.

Citing the U.S. Constitution, several of the “No-No Boys,” now in their 80’s and 90’s, said they were deeply insulted by the questions. Angered and betrayed by the country they loved, they responded by saying “No-No,” qualified their answers, or flat-out refused to sign.

“I was fighting for our civil rights,” more than one said. “This was not right, and we were protesting what the U.S. government was doing to us.”

“I would have served, if they had released us from camp,” said another.

Clearly, this was not a “black and white” issue. For some, it had absolutely nothing to do with loyalty or disloyalty, and everything to do with family.

“My mother insisted that our family stay together,” said one. “That’s why we said “No-No, so our family could stay together.”

Here are some other things I learned at the pilgrimage: After segregation, Tule Lake became a camp full of 18,000 inmates. Because of the chaotic and lawless environment that the camp had become—due to WRA employees stealing food to sell on the black market, military police conducting dragnets throughout the camp and a culture of mistrust from insider “spies” on the WRA payroll—the government put Tule Lake under martial law, 1,200 soldiers were brought in with tanks, machine guns and tear gas, and a stockade was built that included a jail, within what was already a jail.

Without being charged, protest leaders were thrown into the stockade or jail. Some were beaten, others were tortured, according to Tokio Yamane, who was imprisoned in the stockade with two other men; Yamane described the torture of fellow inmate Tom Kobayashi who was beaten with a baseball bat that broke into two from the force of the blow to his head. (At the pilgrimage we saw a DVD interview with Yamane, from his home in Japan. This interview is corroborated by FBI reports of the incident.)

Under duress, over 5,000 individuals renounced their U.S. citizenship, and thanks to a special Federal law passed with them in mind, many of the 5,000+ were legally shipped off to Japan, a country they did not know.

After digesting all of this, my thoughts return to the words, “disloyal,” “trouble maker,” and the “bad people” of Tule Lake, the ones who supposedly brought shame to our community for saying “No-No” when they should have said “Yes-Yes.”

Nisei poet and playwright Hiroshi Kashiwagi, who was imprisoned at Tule Lake from age 20 to 24, stands near what used to be the Tule Lake jail. Castle Rock is in the background.

But after hearing the words from those who were there, I have to wonder: Was it “disloyal” to cite one’s civil rights and protections under the U.S Constitution as their reason for protest? Does protesting an injustice make someone a “trouble maker” and a “bad person?” Wasn’t the Boston Tea Party a form of protest? Isn’t fighting for freedom and democracy the American way?

The saddest part about these words is that for many in our community, they have become the reality, the accepted words to use when describing the people at Tule Lake. Because of this, the “No-No’s” and Renunciants have largely been shamed into silence, their stories ignored in our history, and they, as people, have been placed in the margins of Japanese American society.

The tragedy of it all is that so many—thousands—have gone to their graves with this terrible burden and shame on their shoulders. And for those still living, the pain remains, unresolved, not only for themselves, but for their descendants as well.

On the bus ride home from the pilgrimage I asked a young National Park Ranger serving at Manzanar if he saw any differences between Manzanar and Tule Lake. He thought a moment and said, “At Tule Lake, and among the people I met, I felt a lot more pain.”

And it’s all because of words, these words that have caused so much pain and damage to members of our community, splitting us apart and turning us against each other. We have received redress and reparations, and an official apology from the President. Where now are the words that can begin the healing from within our community?

A former Tule Lake inmate holds some shells she picked up from the Tule Lake grounds. During camp, shells like these were strung up and used for various decorations.

I, for one, will never use the words “trouble-maker” and “disloyal” again to describe the people of Tule Lake. Instead, I will use words to celebrate the fact that despite extremely difficult circumstances, we have MANY courageous stories to tell our future generations: The heroic and amazing story of the soldiers of the 100th/442nd/MIS and 522nd Field Artillery Battalion; the independent spirit and dedication of Nisei women who served in the Cadet Nurse Corps and the Women Army Corps (WAC); the strength and perseverance of the Heart Mountain Resisters of Conscience, the devotion and hard work of the military protesters known as the 1800th Engineer General Service Battalion and last, but not least, the endurance and fighting spirit of the Rebels of Tule Lake.

These are the words I have used to describe our greatest generation: Courageous, heroic, amazing, independent, dedication, strength, perseverance, devotion, hard-work, endurance, fighting spirit, Rebels. To the Sansei, Yonsei, Gosei, Hapa Nation and beyond, this is how they responded—with enormous dignity and Americanism—to the words and actions of a government that had betrayed them.

Embrace them all, choose your own, but know that they existed back then—these stories and our people. And for all that they did, and for all that they suffered, I cannot help but say to them, with deepest respect, gratitude and appreciation: “Thank you. Mahalo. Arigatou.”

And hopefully, now and in the future, they can all be accepted, recognized and acknowledged as the National Treasures that they are.

© 2009 Soji Kashiwagi