>> Page 3

Unlike Armendariz, who chiefly builds her account of El Paso’s early Nikkei community from local newspaper articles, Miyasato relies heavily upon oral history interviews to construct her community narrative. Because these life stories provide a window through which to apprehend the special character of the Japanese El Pasoans and the complex ways they became embedded in the history, culture, and society of the Interior West region, they merit careful attention. The following representative sample focuses on Mansaku Kurita, an Issei man, but it also captures his Issei wife Teru’s experiences.

Around 1910, Mansaku Kurita came to El Paso through Mexico. He once worked for the railroad company, [and] then he started farming in Colorado...In Colorado, he was in real good shape financially, but he got wiped out when his crops failed, so his friend Kuniji Tashiro called him in 1928 to come to New Mexico and farm there for a year. Then he came to El Paso. By the time he settled down in El Paso, he was financially secure. Mansaku married Teru, a woman from Shizuoka [Japan], who was about five years younger than he. When Mansaku called for Teru, she lived in Kansas. Teru had a college education and taught school in Japan. Later she worked as a midwife to many Mexicans in El Paso, and was known as the mother of El Paso.1

For Nikkei, life in Arizona pre-World War II and during the war was markedly different from that in Colorado in important respects. By 1910 Colorado had some 2,500 Japanese immigrants, while fewer than 400 people of Japanese ancestry resided in Arizona; by 1940 Colorado claimed close to 3,225 Nikkei and Arizona nearly 900. The prewar distribution of these two states’ Nikkei populations was also very different. Most Japanese Coloradans were scattered around their state in modest-sized farming communities; there was also a comparatively dense cluster in the area of Denver, where they were supported by the budding Japantown located within the city’s deteriorated core. In contrast, Japanese Arizonans—who were primarily agriculturalists—congregated in the Salt River Valley’s Maricopa County, in central Arizona, where they found rudimentary ethnic support systems in Phoenix, Glendale, Tempe, and Mesa.

Another distinguishing feature differentiating life for Japanese in Arizona and Colorado during this era is that Nikkei in Arizona had to contend with a greater degree of legal and extralegal prejudice, discrimination, and outright racism than those residing in Colorado. This is not to say that Colorado’s anti-Japanese climate was mild or sporadic—in fact, it was both severe and unremitting, as historian Kara Miyagishima has copiously documented. In the early twentieth century, because Colorado’s laboring class generally viewed “little yellow men” from the Far East to be “invading” their state and, as railroad, mining, and farm workers, they were felt to be posing unfair employment competition. To counter this perceived problem, labor groups excluded them by creating associations such as the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League founded by the Colorado State Federation of Labor in 1908. Even after the Issei bachelors progressively transformed the Nikkei population within Colorado from one dominated by mobile laborers with a bird-of-passage mentality to one characterized by stabilized family-based farm and commercial enterprises, nativist groups organized against the Nikkei to hinder their ascent of the social and economic ladder. “Like the Negroes of the South,” writes Miyagishima, “the Japanese were accepted without rancor only so long as they remained in their place.”2 In Denver, where by 1920 some 85 percent of the population was native-born, restrictive covenants and similar segregating mechanisms were imposed, leaving only the city’s Skid Row area open for residency by Nikkei and other people of color. With the onset of World War II, Colorado—and Denver, in particular— experienced a large infusion of Nikkei from the West Coast. Many arrived in Colorado during the period of “voluntary evacuation” and afterwards, with a large number settling there as a consequence of temporary work leaves and semipermanent resettlement from the WRA camps.

With an increase in Nikkei residents came a sharp increase in anti-Japanee sentiment and activity. The state’s major newspaper, the Denver Post ,3 became America’s most venomous journalistic purveyor of Nikkei race-baiting. It pervasively promoted the notion that Japanese Americans “were not genuine U.S. citizens, but unassimilable and untrustworthy,” unacceptable even to harvest the state’s direly endangered sugar beet crop, and altogether unwanted in Colorado without strict federal and military supervision and control. The Post also helped to provoke a rising wave of vigilante violence against Nikkei and championed the 1944 campaign mounted for a state constitutional amendment to restrict land ownership by alien Japanese residents (as well as East Indians, Malayans, and Filipinos).4

But the anti-Japanese movement in Colorado, from the early twentieth century through World War II, always had to contend with countervailing forces. Some came from within the Nikkei community, which possessed sufficient numbers to command the Japanese government’s attention and to capitalize upon its considerable international power and influence. Nikkei had also developed an institutional network that could resist—or at least deflect—oppressive measures and campaigns designed to inflict damage upon or destroy Japanese Colorado. Thus, in 1908, to protect the interests of Japanese against the Colorado State Federation of Labor’s Japanese and Korean Exclusion League and similar organizations, the state’s Issei established, in Denver, the Japanese Association of Colorado. Along with other Japanese Association branches that developed throughout Colorado, it concurrently forged political ties to the Japanese government and encouraged the assimilation of Japanese Coloradans. This situation no doubt was a key reason why Colorado, unlike most other Interior West states, did not institute an anti-Japanese alien land law.

Although an attempt was made to do precisely that during World War II—at a point when mainstream negative feeling toward the Nikkei was at its zenith—via a state constitutional amendment, what transpired showed that the Japanese American community could count on countervailing support on its behalf outside the boundaries of its ethnic subculture. In seeking to counteract the drive for the amendment, which was spearheaded by the American League of Colorado in conjunction with such other supporters like the Colorado Veterans of Foreign Wars and citizens of Brighton and Adams counties (most of whom were truck drivers of Italian descent), the Nikkei were aided by a diverse array of backers. Organizations who sided with the Japanese in opposition to the amendment included a Citizens Emergency Committee formed by ministers and educators (with a statewide executive committee made up of prominent citizens), which disseminated its message via public meetings, newspapers, and radio; the Denver Council of Churches; the Denver YWCA; the Colorado State League of Women Voters; the Denver-headquartered National Civic League; the Cosmopolitan Club, a student organization at the University of Colorado; the Rocky Mountain Farmer’s Union; and mainstream newspapers like the Rocky Mountain News and the Pueblo Star Journal and Chieftain , as well as vernacular newspapers such as the Intermountain Jewish News and the Colorado Statesman and the Denver Star (both of which were African American publications). As a result of this diverse support, the amendment was defeated.5

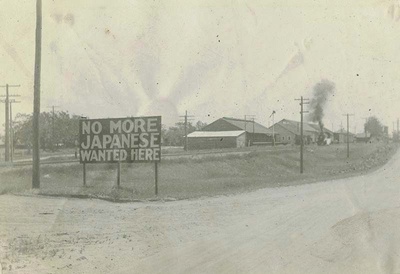

Anti-Japanese sign in Livingston, California, ca. 1920-1930. Gift of the Yamamoto Family, Japanese American National Museum

The smaller number of Issei in pre-World War II Arizona—as well as the state’s proximity to California, where anti-Japanese emerged earliest and most intensely—made Japanese Arizonans more vulnerable than Japanese Coloradans to racist mainstream attacks. Thus, as Eric Walz has documented, beginning in 1913, the state’s Nikkei farmers had to contend with the alien land law that Arizona (following California’s lead) passed that year; this law forbade members of racial groups ineligible for U.S. citizenship, which included the Japanese, from purchasing land but did permit them to enter into leasing arrangements.6 An attempt was made in 1921 to legally close this loophole, although Issei circumvented the new law by leasing land in their children’s names or through non-Japanese landlords and neighbors. Still, the Issei were swimming against the tide of public opinion, for “non-Japanese farmers in Maricopa County,” to quote Walz, “resented competition from Japanese immigrants . . . and accused the Japanese of using unfair labor practices (Japanese wives and children worked in the fields), of paying too much in rent, and of taking up the best farmland in the [Salt River] valley.”7

In late 1923, the Maricopa County Farm Bureau’s president forwarded Arizona’s governor a Farm Bureau resolution opposing creation of a Japanese population with the potential to “expand in time and prove to be undesirable residents” and requesting “a strict enforcement of the Arizona Statute which forbids the selling to [Japanese] or leasing of farming lands in this state.”8 In reply, the governor promised to urge the state attorney general and the county attorneys to strictly enforce the laws. Notwithstanding this official resolve to see that the alien land law’s spirit as well as its letter were respected, the Issei community was “cohesive enough to defend itself”: while Japanese immigration was slowed, “the number of Japanese farm operators in Arizona increased from sixty-nine in 1920 to 121 in 1930.”9

By the early 1930s, with the Depression in full swing, this situation was reversed. In that dire economic climate, the market value of agricultural products was slashed, and a series of circumstances led to Japanese farmers essentially monopolizing cantaloupe production. They also enjoyed a bumper crop that, confronted by very little competition, brought windfall profits even as Maricopa County’s non-Japanese farmers, who had reduced their sideline cantaloupe acreage, were hit by dismal returns for their principal cotton and alfalfa crops. As a consequence, strong anti-Japanese sentiments—including enforcement of the alien land laws—came to the fore once again. The capstone to this escalating racist climate was the explosive situation that Eric Walz has so graphically depicted:

On August 16, 1934, 600 Caucasian farmers met in Glendale to decide how to rid the [Salt River] valley of their Japanese competitors. At a rally the following day, more than 150 cars paraded through town. One carried a banner that read:

WE DON’T NEED ASIATICS

JAP MOVING DAY AUGUST 25TH , WE MEAN IT

MOVE OUT BY SATURDAY NOON AUGUST 25TH

OR BE MOVEDOver the next few weeks nativists and their minions flooded Japanese farms, bombed Japanese homes, pushed pick-ups owned by Japanese farmers into irrigation canals, and fired shots at Japanese farmers who tried to protect their growing crops.10

A bloody catastrophe was prevented by timely intervention by the general community’s educational and religious leaders, Arizona Japanese Association lobbying efforts, and the local Japanese community’s appeals to the Japanese consulate. However, in the long run persecution was halted by economic pragmatism: the Mitsubishi Company, a large Southwest cotton purchaser, warned that the price of persisting violence against Japanese farmers would be the loss of cotton contracts; the U.S. government also made it clear that federal water projects for Arizona would be put at risk should the maltreatment of Japanese farmers continue. But the damage had already been done. While few Japanese farmers actually left the valley as a direct result of violence,” concludes Walz, “discrimination and depression reduced their numbers in Arizona from 121 in 1930 to 52 by 1940.”11

In prewar Arizona’s towns and cities there also existed racist feelings toward Nikkei (as well as other people of color) which had hardened into customs and institutional practices. Susie Sato, an Arizona native reared in Lehi, a small Mormon community in the central part of the state, has testified that while the kindness of Mormon neighbors mitigated prejudice against her Nikkei family, she encountered discrimination at movie theaters and swimming pools in the municipalities surrounding her hometown. Nikkei, along with other Asian Americans, Mexican Americans, African Americans, and Native Americans, “were not permitted to swim in the Tempe public pool, and throughout the [towns of the] Phoenix area, movie theaters practiced a strict policy of segregation.”12

Notes:

1. Miyasato, “The Japanese in the El Paso Region,” p. 21. Although the names in this mini-biography were rendered in the Japanese mode—family names preceding given names—they have been reversed to reflect the American naming style.

Miyasato’s study of the Japanese in El Paso does not end with World War II, an event that “fragmented psychologically the small number of Japanese living in the region.” Instead, she reveals how a new El Paso Nikkei community was formed in the post-World War II years by an amalgam of Japanese Americans, Japanese-Mexicans, and Japanese war brides who, during World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, came in substantial numbers from Japan (where they met and married American soldiers—including, increasingly, African Americans—stationed there) to live in the El Paso area with their husbands at the nearby Ft. Bliss military base. See ibid., pp. 38 and 38-92 passim, especially 38-53.

2. Kara Mariko Miyagishima, “Colorado’s Nikkei Pioneers: Japanese Americans in Twentieth Century Colorado” (master’s thesis, University of Colorado, Denver), p. 124

Miyagishima’s study and another recent work by the late Bill Hosokawa—Colorado’s Japanese Americans from 1886 to the Present (Boulder, Colo.: University Press of Colorado, 2005)—cover the same general historical territory. However, Hosokawa does so in an episodic, anecdotal, and engagingly colorful and palpable way without benefit of footnotes, while Miyagishima fashions a narrative featuring lineal chronological development, exacting factual detail, contextual amplification, extensive documentation, and clear writing. Accordingly, these two texts very nicely complement one another in style as well as content.

3. For an assessment of the Denver Post ’s anti-Nikkei campaigns, see Kumiko Takahara, Off the Fat of the Land:The Denver Post’s Story of the Japanese American Internment during World War II (Powell, Wyo.: Western History Publications, 2003).

4. See Miyagishima, “Colorado’s Nikkei Pioneers,” pp. 57-178 passim, but especially pp. 57-60, 122-26, and 175-78.

5. Ibid., 177-8. It should be noted, however, that the legislative vote on the measure (the Senate’s narrow victory margin of 15 to 12 and the House’s overwhelming repudiation of 48 to 15) highlighted the prevalence of anti-Japanese sentiment in Colorado.

6. Eric Walz, “The Issei Community in Maricopa County: Development and Persistence in the Valley of the Sun, 1900-1940,” Journal of Arizona History 38 (Spring 1997): 1-22.

7. Ibid., pp. 8-9.

8. Ibid., pp. 9-10.

9. See Vicki S. Ruiz, “Tapestries of Resistance: Episodes of School Segregation in the Western United States,” in Peter F. Lau, From the Grassroots to the Supreme Court: Brown v. Board of Education and American Democracy (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2004), p. 55. See also the following sources: Susie Sato, “Before Pearl Harbor: Early Japanese Settlers in Arizona,” Journal of Arizona History 14 (Winter 1973): 317-34; Mesa Historical Museum, “Mesa Leadership Talk with Angy Booker, Celia Burns, and Susie Sato,” audio recording, November 1, 2003 at the Mesa Historical Museum in Mesa, Arizona; and Valerie Matsumoto, “’Shigata Ga Nai ’: Japanese American Women in Central Arizona, 1910-1978” (senior honors thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, 1978); and Valerie J. Matsumoto, “Using Oral History to Unearth Japanese American History,” presentation at Japanese Americans in Arizona Oral History Project Workshop, Arizona State University, Tempe, November 8, 2003.

© 2009 Arthur A. Hansen