Read Part 5 >>

Ansel Adams: Gifted Pianist Turned Master Photographer

By the time he arrived at Manzanar in October 1943 for the first of four working visits, Adams was a successful and famous photographer. He had helped launch the short-lived but important organization of West Coast photographers Group f/64, had exhibited in New York, had published a book (Making a Photograph), and had befriended a gallery of visionary artists, curators and writers, including Paul Strand, Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keefe, Edward Weston and curators and writers Beaumont and Nancy Newhall. He was hardly a political activist, although Adams scholar Anne Hammond says that as a young man in the 1930s, “Adams was (like many young people of that era) very sympathetic to the left, arguing on behalf of unions with his father, and eventually amassing an FBI file on him eight pages long.

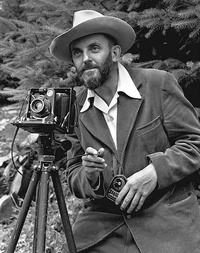

Photographic portrait of Ansel Adams, which first appeared in the 1950 Yosemite Field School yearbook. Photo by J. Malcolm Greany. (Source: wikipedia.com)

As a boy, Adams was hyperactive and ill-suited for school. His father recognized Adams’s musical talent and intellect and hired tutors and a piano teacher. He also gave his 13-year-old son a yearlong pass to the enormous 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition that spread over and transformed what is today San Francisco’s Marina district. The fairgrounds became the restless boy’s school for a year. A gifted musician, he contemplated becoming a concert pianist but eventually decided to concentrate on his other great love: photography. Adams’s love for both photography and nature – especially the Sierra Nevada mountain range, with which he would become inextricably identified—seemed to develop almost in tandem. The catalyst was a gift from his parents of a Kodak Brownie box camera during his first trip to Yosemite when he was 14.

In 1930 he met the influential socialist photographer Strand, and was powerfully affected by Strand’s formal, abstract images and somber portraits (“perfect, uncluttered edges and beautifully distributed shapes…simple yet of great power,” Adams wrote). Strand’s work revealed to the fledging photographer Adams the expressive possibilities of the medium and gave him the conviction to choose photography over the piano. The two photographers remained friends without sharing political views. In the 1940s, Adams joined the Photo League, a progressive cooperative of amateur and professional photographers that Strand co-founded with Berenice Abbot. In 1947, the U.S. Justice Department targeted the group as a “subversive organization” because of its ties to socialist and communist groups. Strand, a committed Stalinist who was considered the Photo League’s patron saint, spoke eloquently in defense of members’ civil rights. Adams—who opposed both the extremes of fascism and communism—wrote in his biography that he beseeched the Photo League to renounce all political involvement of any sort. When it did not, he resigned from the group. Aside from his youthful sympathy for leftwing politics, Adams’s political activities were confined to issues of nature conservation.

Adams and the Making of Born Free and Equal

Adams’s work at Manzanar arose, according to his 1985 autobiography, out of frustration at not being able to serve his country during World War II. He was too old to fight, and the handful of civilian assignments he landed did not satisfy him. When he expressed this feeling to his old Sierra Club friend Ralph Merritt, project director at Manzanar, Merritt suggested that he document the camp. In Ansel Adams: An Autobiography, Adams acknowledged that Lange’s earlier photographs of the camp “reveal the despair, bewilderment, and misery of the thousands of American citizens as they were apprehended and isolated almost as prisoners of war.” Yet he added reassuringly, “While the first months at the camps were bleak and severe, there was none of the neglect and brutality we associate with European and Asiatic concentration and POW camps.”

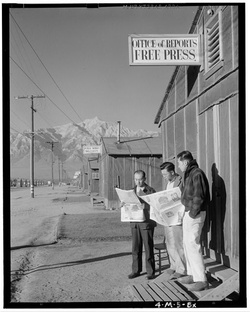

Editor Roy Takeno (left), Nobuo Samamura and Yuichi Hirata peruse a copy of "The Los Angeles Times" in front of the ironically titled Manzanar Free Press office, from "Born Free and Equal" (Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

The Manzanar Adams encountered in 1943 had, thanks to inmate labor, been transformed from barren wasteland into a tidy but still desolate compound. The industrious work of incarcerated Manzanar residents had created a functioning community, complete with hospital, self-run consumer cooperative, farms and gardens, newspaper, school and clubs. With the aid of irrigation, which the prisoners had engineered, they had coaxed bumper crops of fruits and vegetables out of the once arid soil, enough to both feed the inmates at Manzanar and sell to buyers outside the camp. Fresh fish was available, courtesy of connections maintained by prisoners who had worked as fishermen. Residents created plays, paper flower displays, sports leagues and clubs for every interest and activity. Adams described Manzanar at this point as “a little city, well-governed and alive, mirroring in small scale an average American metropolis.” The truth was somewhat different: Manzanar was a concentration camp, with inferior hospital equipment and supplies and makeshift educational and athletic facilities. Some inmates slid into depression or alcoholism, some died from lack of adequate care.

Adams shared the view of many liberal-minded Americans that the hard work and obedience of inmates had proved their loyalty; the question was how to integrate them back into society. To illustrate his vision of Manzanar as a government-sponsored job-training center and benign microcosm of American life, Adams filled Born Free and Equal with portraits of workers, often identifying them not by name, only by occupation — “a welder,” “a tractor farmer” or “a rubber chemist.” The picture of the well-coiffed young seamstresses in training bears the caption, “The young people receive extensive vocational training.” Pictures of choir practice, baseball games, a group of nurses playing cards during a break all reinforce the image of a Japanese Mayberry.

Adams's caption for his picture of nurse Aiko Hamaguchi and other members of the Manzanar Hospital nursing staff read, "Relaxing in the nurses quarters." (Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

As befitted Adams’s assimilationist aspirations for the Japanese, he published no pictures of unhappy, sullen or angry-looking people. Nor did he publish images of internees practicing traditional Japanese arts and crafts such as Japanese dance, flower arranging or New Year’s mochi (rice cake) pounding, or martial arts such as judo and kendo, all kept alive in camp and documented by Miyatake.

Adding a sense of spiritual uplift to Adams’s utopian vision of Manzanar was the natural splendor of the valley, what he called “a mood of sunlight and the grandeur of space.” (See Part 10 for descriptions of two photographs that captured these qualities, Winter Sunrise, The Sierra Nevada, from Lone Pine California 1944 and Mount Williamson, Sierra Nevada, from Manzanar, California.) To Adams, Manzanar was “only a rocky wartime detour on the road of American citizenship…a symbol of the whole pattern of relocation—a vast expression of a government working to find suitable haven for its war-dislocated minorities.” As a package, Adams intended these disparate elements of Born Free and Equal to add up to a ringing endorsement of the Japanese people. Yet as we will see, this last phrase, in particular, provoked a different sort of reaction.

© 2011 Nancy Matsumoto