Meet Tatsuo Tomeoka, whose website (http://mingei-wasabidou.com/), is most attractive for those interested in the Arts of the People. Tatsuo is a young Nisei born from immigrant Japanese parents in Seattle, in 1961…far away from the time when being of Japanese descent was a capital sin in our country.

Without the internment experience in my background, he says, I was never sure if I was a ‘Japanese-American;’ an ‘American of Japanese descent’ or just ‘Japanese’ or ‘American.’

Tats grew up in Seattle, but spent quite a number of summers in Japan, at times training in kendo and wrestling at the conservative Kokushikan University in Tokyo. After wrestling stints at both UCLA and San Francisco State University, he did not graduate. However, at 35, and after several return trips to Asia, he experienced his own epiphany, and returned to school to complete his degree in Japanese Studies, at the University of Washington’s Jackson School of International Studies.

Mashiko chawan (tea cup) & Dobin (tea pot); Mingawa Hiro, Mashiko, 1999. (Photo courtesy of Tatsuo Tomeoka)

“My focus at that time was Mingei Biron, the Folk Craft Theory of Yanagi Soetsu….I didn’t really start ‘collecting’ Mingei on my own until I was about 30,” he says. Like many of us he had at home various items, mainly omiyage—kites, wooden toys, furoshiki, and other souvenirs that helped him appreciate the beauty of handcrafts.

“Also, at home there were kokeshi, received from my mother’s side of the family who hail from Miyagi Prefecture. I don’t think I appreciated their true Mingei nature until I was much older (and man enough to admit to ‘collecting dolls.’)”

What is this Mingei which triggered our friend Tatsuo’s epiphany?

As Japan entered the turbulent age of industrialization, Dr. Sōetsu-Muneyoshi1-Yanagi (柳宗悦), (1889–1961) felt saddened as he saw how cheap, machine-produced items were quickly displacing getemono, the traditional household effects, which anonymous artisans crafted from clay, paper, bamboo, wood, stone, lacquer, straw, and fibers. For centuries, unknown craftsmen unbound by Fine Arts’ dogmas had fashioned versatile, functional, simple and durable pieces loaded with splendid finery, which enriched the lives of their daily users. As results of his enlightenment, Dr. Yanagi embarked on an ambitious project to salvage those items from oblivion; and began collecting them earnestly.

“I will continue to collect at my best with what little resources I have, he wrote, for there is where I find meaning in life—my reason for being born.”

Miharu Hariko Tora (paper-mache tiger from Miharu Village, Fukushima Prefecture,) 2010. (Photo courtesy of Tatsuo Tomeoka)

With his passion for collecting, and his deep insight on the creative process Yanagi could have become a successful owner of a great gallery. Instead, he chose to carve a niche in the Philosophy of Art2 for local or regional Japanese and Asian getemono and their creators. To accomplish his goal, he crafted the concept Mingei synthesis of minshu-teki-kogei, the People’s Art.

In 1919, Yanagi was appointed Professor of Religious Studies at Toyo University. In that same year, Asakawa Noritaka, a schoolteacher in Korea brought to him some glazed ceramics from the Korean Joseon Dynasty, (1392–1910). As he admired them, Yanagi said:

I had never dreamed of discovering in cold pottery such warm, dignified and majestic feelings. As far as I know, the people with the most developed awareness of form must be the ancient Korean people.

Yanagi saw Korean artistic expressions as the result of that nation’s turbulent past. Initially a series of independent kingdoms—often at war with each other3—Korea was invaded in 1238 by the Mongol, who remained there for 30 years. Taiko Hideyoshi came next, in 1592 and 1598. The Manchu followed in 1627 and 1636. Then, after 27 previous years of messing up Korea’s political affairs, Japan came again in 1897; and finally annexed it in 1910. Yanagi believed that, as result of so much turbulence, the Korean artisans had developed an innate, original beauty minzoku no koyū no bi, which he saw reflected in the sad and lonely lines of their pottery.4 He became so fond of Korean culture that, in 1924, he established the Chôsen Minzoku Bijutsukan, National Folk Museum of Korea5 in Seoul.

National Folk Museum of Korea located in Gyeongbokgung Palace, Seoul, Korea (Photo by Isageum. From wikipedia.com)

Some Korean writers have called Yanagi’s concept hiai no bi, the beauty of sadness, the aesthetic of colonialism. However, other distinguished scholars such as Art Historian Hong-jun Yu, and Yong-ho Choe, Professor Emeritus of Korean History at the University of Hawaii, fondly recall Yanagi’s intense love for Korean Art, and his courageous stand against Japanese destructive colonial policies. For his criticism of Japan’s colonialism, Yanagi became a suspect to the Japanese police who constantly shadowed him and monitored his activities.

Yanagi also discerned great dignity, majesty and originality in the works of the Japanese common artisan, often-innocent victim of protracted internal wars, an opprobrious and monolithic caste system, and the rigid isolationism of Tokugawa’s sakoku, chained country.6 In 1926, he founded the Nihon Mingei Kyokai, Japan Folk Crafts Association, with potters Shôji Hamada, (more on him later) Kenkichi Tomimoto, Kanjirô Kawai, and British Bernard Leach. The group’s purpose was to curate objects it considered irreplaceable treasures; to share such treasures with the public at large; and to secure recognition and economic support for the equally irreplaceable and dwindling group of craftsmen that made them. In the 1930’s, Yanagi became also interested in the crafts of the peoples of the Ryukus, the Hokkaido Ainu; and on those of Taiwan and Manchuria, then Japanese colonies. Between 1927 and 1935 the group conducted a series of crafts exhibits; then in 1936, in the Meguro section of Tokyo, it opened the Nihon Mingeikan, Japan Folk Crafts Museum.

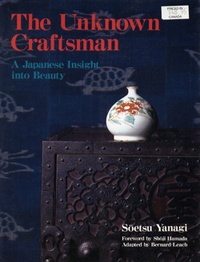

Yanagi wrote extensively, in Japanese,7 on Mingei objects and Mingei theory. A selection of his writings was translated into English by Bernard Leach, to create the memorable book The Unknown Craftsman,8 which clearly explains Yanagi’s concepts; evinces their strong ties to spirituality; and details the genesis of the museum. Leach took ten years to translate the original text, which he enriched with his own insights.

Before the Pacific War, Yanagi was invited by Harvard, to lecture for a year; and after the war, he also lectured all over Europe and the United States. With time, he found enthusiastic supporters in many parts of the world, and of course, such success triggered criticism. In 2004, Dr. Yuko Kikuchi, Senior Research Fellow at London’s Chelsea College of Art and Design wrote a book with the sesquipedalian title: Japanese Modernisation and Mingei Theory: Cultural Nationalism and Oriental Orientalism. From what sounds like a Eurocentric viewpoint, Kikuchi fully sassed Yanagi and his theories as one more lump in Japan’s era of militarism.9 Brian Moeran, Director of the Centre for Creative Industries at the Copenhagen (Denmark) Business School, also criticized Yanagi, though less severely.10

Yanagi’s theories and work have triggered an overdue awareness about the artistic value of objects produced by unpretentious common artisans for the benefit of all of us.

In his essay Folk Crafts in Japan he wrote:

...when beauty is an integral part of the life of the people…the Kingdom of Beauty may be realized on earth.11

Notes:

1. Sōetsu and Muneyoshi are alternative readings of the same kanji.

2. As results from his deep studies on mysticism, and especially his close association with Buddhist scholar Daisetz Suzuki, Yanagi enriched the Mingei philosophy with a strong dose of spirituality and Buddhist aesthetics. For his work, Yanagi was honored as a Living National Treasure by Japan.

3. In several instances, starting in the fourth century, Japan became a military ally of one or another of the Three Korean Kingdoms, in some of their internecine campaigns.

4. Yanagi, Sōetsu. Korea and its Art. Tokyo: 改造 Kaizō-September 1924.

5. During the American Occupation of Japan, the name was changed, on November 8, 1945, to National Folk Museum of Korea.

6. Yanagi. The Collection of the Japan Folk Crafts Museum. Nippon Mingeikan EXPO’70 Catalogue. Tokyo. 3.15~9.13

7. Yanagi Sōetsu Zenshu, (Collected Works of Yanagi Sōetsu). Tokyo: Shikuma Shobō. 1981.

8. Tokyo, New York: Kodansha International, 1989. See also:

Munsterberg, Hugo. The Folk Arts of Japan. Rutland, Vermont and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle. 1958

9. RoutledgeCurzon, 2004. Kikuchi depicted Yanagi as a narcissistic, jingoistic, upper class copy-cat who Japanized the ideas and techniques of William Morris, John Ruskin, Tolstoy, and the Nordiska Museum in Stockholm.

10. Moeran, Brian. “Bernard Leach and the Japanese Folk Craft Movement: The Formative Years.” Journal of Design History, Vol. 2, No.2/3, (1989): 139-44

11. Tokyo: Kokusai Bunka Shinkokai. 1956.

© 2010 Edward Moreno