The Steveston Japanese Fishermen’s Hospital came into being unexpectedly and, in reviewing its history, the reader will realize that its birth, though understandable, was anything but planned. It is now seen as a symbol of honour for a much maligned minority.

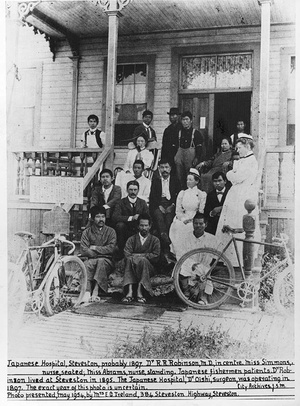

When a dentist, Dr. Umejiro Yamashita, and a surgeon, Dr. Seinosuke Oishi—both from Japan—came from Portland, Oregon and urged the building of a church in Steveston, BC for Japanese fishermen in 1895, their intention was not to create a medical facility for sick fishermen. These volunteers from the Pacific Coast Japanese Christian network were concerned about saving the men from debauchery and drunkenness. To these devout Christians, these sins were the disturbing signs that offended them in the new frontier town of Steveston which had sprung up around the fish processing industry, accompanied by bars, brothels, and gambling dens—a common occurrence in such mostly-male communities.

The doctors strongly urged the local Christian leaders to build a church to rescue the men from sin by leading them to take up wholesome and practical pursuits like the study of English and the Bible. In support of such aims, the Phoenix cannery provided the land on which a two-story church was built in 1895—the first floor to provide rooms for gatherings and teaching; the second floor to serve as the manse.

Typhoid was in those days a most dangerous illness, with a high death rate if left untreated. There were also other infectious diseases such as yellow fever and scarlet fever. The Japanese were the most susceptible to these diseases. Japan was blessed with abundant potable water from short, clean streams which encouraged the custom of drinking untreated water. They also ate raw fish which could harbour dangerous bacteria.

In stark comparison were the Chinese, who made up the bulk of cannery workers and came from a country with long, polluted rivers. They customarily boiled their water before drinking it as tea. At that time, the Fraser River was the most common source of drinking water. It was free whereas it cost money to obtain water transported from New Westminster and Marpole. Unfortunately, upstream and local fish canneries dumped fish waste, and many toilets emptied their refuse into the river, so water-borne diseases took their toll for some years. Eventually, local authorities replaced the Fraser River water with piped Capilano Lake reservoir water from north of Vancouver, and put in a proper sewage system.

In 1897 as many as 26 local Japanese and 12 aboriginals died of typhoid (Ross). Among the Chinese, their habit of drinking only boiled water saved them—not one died of typhoid in Steveston that year. When an outbreak struck that summer during the fishing season, the church was quickly converted to meet the emergency, and it became a temporary hospital and its members served as hospital staff.

In recognition of this conversion, it became known locally as the Chapel Hospital and was in operation during the July to November fishing season for several years, reverting to its role as a chapel from December to June, and then back, until 1900 when the Japanese Fishermen’s Benevolent Association built its own hospital.

The Japanese Fishermen’s Benevolent Association (known to the Japanese as the Dantai) accepted responsibility for the hospital as a service vital to its members because of their high susceptibility to such diseases. The local Japanese Christians had very generously assumed responsibility in time of need but could not be expected to continue indefinitely.

The 1897 Constitution of the newly established Dantai had only 11 Articles. Article 1 was a comprehensive statement advocating the “advancement of the fishermen in all things.” Three other articles directly mention the hospital and its upkeep as a major responsibility of the Association. This shows how serious a threat such diseases were at that time to Japanese fishermen and their families. The association had no choice but to include the hospital in their operations. The nearest other hospital was in New Westminster and the fishermen’s lack of English, especially in the early years, made it so much easier for them to talk to medical staff in their own language.

Non-Japanese residents of Steveston also received medical care at the Fishermen’s Hospital from the beginning. According to Harold Steves Jr., currently the longest-serving Richmond City Councillor, his father, Harold Sr. was not only born in the hospital in 1899 but also spent months there some years later being treated for typhoid fever. The younger Harold says that his father’s hair turned white from the disease and because they had so often fed him junket at the hospital as something his stomach could tolerate. He developed a life-long dislike for that dessert (personal communication, June 2012). Steveston is named for their ancestor Manoah Steves who first settled in that corner of Lulu Island in 1877.

It is difficult for young Asians growing up in British Columbia today to believe that, until about 1950, Canada’s western-most province was inhospitable to Asian immigrants. The biggest threat to their welfare then was the Asian exclusion campaign waged by the white labour unions (including fishermen’s union) and the politicians who used Asian-baiting as an easy means to garner votes from the majority white voters who saw Asians as a direct threat to their economic well-being.

In 1895 British Columbia passed a provincial law denying the vote to Asians, whether born in Canada or naturalized citizens, and to aboriginals. Tomekichi Homma, the first president of the Japanese Fishermen’s Association, a naturalized Canadian citizen like all licensed Japanese fishermen, was chosen to take the case for franchise all the way to the Privy Council in London in 1902. They fought the 1895 law on the grounds that a naturalized citizen is a citizen. Unfortunately and unexpectedly, the case was lost there after having been won at the provincial higher court and the Supreme Court of Canada. The hostility of the majority white race to their presence was constantly in their faces in this period and reached its first peak in the Anti-Asian Riot in Vancouver in 1907. The Anti-Asian movement had succeeded in obtaining the levying of a “head tax” on Chinese immigrants, beginning in 1885 at $50 and rising to $100 in 1900 and to $500 in 1903. They tried to have these measures extended to the Japanese but the Japanese had a greater leverage in Ottawa than the Chinese due to the Anglo-Japanese military alliance. The Japanese saw that, in order to change their own social and legal status, they would have to convince the white majority that they were an honorable people with a strong sense of public responsibility.

At the end of the first year of operations, the hospital had incurred a debt and a meeting was held including others of the BC Japanese community to deal with this issue. The Japanese Consul in Vancouver, Tetsugoro Nosse spoke at this meeting and told them about having begun a personal campaign to combat the anti-Japanese propaganda in Canada. He had seized upon the Steveston Japanese Fishermen’s Hospital as the most suitable symbol of the community-mindedness and responsible citizenship of the Japanese immigrants, as well as the churches and schools which they had built in spite of the few years they had been in Canada. He visited Ottawa, to call upon government ministers, members of parliament, and newspaper editors, to hand out a pamphlet he had printed with the story of these symbols of good citizenship.

At the end of his rousing speech, the Consul called upon the Fishermen to uphold the honour of the Japanese in Canada by maintaining the hospital and, with community support, to find the solutions to their inevitable financial difficulties because the reputation of all Japanese in Canada was in their hands at this critical time.

The general acknowledgment in the community that the hospital was an important part of the public image of all Japanese allowed them to accept the $200 gift that Prince Arisugawa had left to the immigrant community in BC. They used it toward the $400 debt incurred in the first year of operation. In so doing, they also inherited an obligation to maintain the hospital—an onerous burden in difficult times.

The Fishermen’s Association maintained the Japanese Fishermen’s Hospital until 1942, when the Japanese were banished from the Pacific coast and the hospital was taken over and renamed The Steveston Hospital (Ross p.163).

The importance of socialized medical services to Canadians was confirmed by the CBC’s national public poll of 2004 when Tommy Douglas was voted the greatest Canadian of all time as the founder of Medicare in 1962 in Saskatchewan. Douglas had launched an earlier version as a hospital insurance plan in 1947.

As Bill McNulty observes in his recent book on Steveston, the Japanese Fishermen’s Hospital was the first of its kind in Canada in providing a health care program based on a modest annual membership fee ($8 a year). In 1897, it was fifty years ahead of the Saskatchewan medical plan. Unfortunately, in the first half of the 1900s, anti-Japanese sentiment in B.C. was too high to allow the Japanese to be judged dispassionately and Consul Nosse’s hope that they would be found praiseworthy for their hospital was in vain in that period.

The hospital has only belatedly come to be seen as a symbol of the community-mindedness of the Japanese immigrants, and only after Japanese Canadians have come to be seen as worthy citizens and positive contributors to Canadian society. In that same CBC poll, David Suzuki, the most well-known Japanese Canadian, placed 5th—and shares a spot on that roster of greatest Canadians with only one other obviously non-white Canadian—Tecumseh, 37th—to crack the top 50.

References:

Teiji Kobayashi, 35 Year History of the Steveston Fishermen’s Benevolent Association (in Japanese), 1935 Tokyo.

Bill McNulty, Steveston: A Community History, 1859-2011, 2011.

Leslie J. Ross, Richmond, Child of the Fraser, 1979.

Mitsuo Yesaki, Sutebusuton: A Japanese Village on the British Columbia Coast, 2003.

*This article was originally published in Nikkei Images (Summer 2012 Vol. 17, No. 2), a publication of the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre.

© 2013 Stan Fukawa