There are many untold and, possibly, forgotten stories in one’s family history. In an earlier article in the 2011 Holiday Issue of Pacific Citizen, the official newspaper of the Japanese American Citizens League, I wrote about what little I knew and what I didn’t know about my father’s incarceration in Jerome during World War II.

Even before that article was published, I began to research the files of persons incarcerated in War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps that were available through the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). I requested and obtained over 200 pages of documents related to my father and two grandfathers. Eighty-eight of those pages belong to my father and include medical records, employment records, travel documents, and a transcript of an October 1943 interview in Jerome. I also obtained Census records and various other documents. From these records, I began to piece together a partial story of his life during World War II.

My father was Kibei, born in the United States, but educated in Japan. After his return to the United States in 1937, my father was a farm worker traveling across California. In 1940, my father was working in Nipomo, San Luis Obispo County and lived with a group of Japanese American and Filipino farm laborers who were working for George Aratani’s Guadalupe Produce Company. Among these men were Tokio Yonekawa and Susumu Watanabe. During the War, Mr. Yonekawa was incarcerated at Poston (Arizona) and, in 1944, joined the military to be stationed at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, home to the MIS. Mr. Watanabe would join the Army before the War started and later joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team at Fort Shelby, Mississippi. Unlike his two friends, my father was not called to serve because he was declared 4F when he registered for the draft.

After the “evacuation” order was issued, my father was sent to the Fresno Assembly Center in the Fresno County Fairgrounds with his father, sister, and her family. They stayed there from May through October 1942 before boarding a train bound for Jerome, Arkansas.

From what I can discern from the records, the early part of my father’s life in camp was relatively uneventful except that he had a number of work related accidents. That relative calm changed in early 1943, when the government distributed a set of forms to the Japanese Americans and Japanese in the camps.

The first was a rather innocuous looking form titled Statement of United States Citizen of Japanese Ancestry. My impression of the Statement was that it was designed with the intent of determining if the citizen would volunteer and be suitable for military service. The second was a short form of the Application for Leave Clearance.

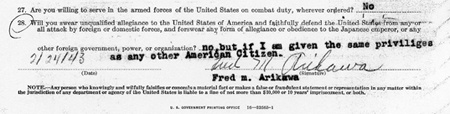

The Statement contained the infamous questions 27 and 28:

27. Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?

28. Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?

My father would have been upset with having to answer these questions.

First of all, he had registered for the draft, so he must have accepted military service as a duty of a citizen, if only grudgingly. Why ask him a second time? Probably more aggravating to him was that he had been declared 4F because he walked with a severe limp as a result of a childhood illness, so there would really have been no point to him volunteering.

From what I could gather from these documents, my father’s friends in camp were also upset. With their urging, my father answered “No” to question 27 and to question 28:

“[N]o, but if I am given the same privileges as any other American Citizen.”

This made him a No No Boy, among a group of Japanese Americans who refused to volunteer for military service and who refused to forswear an alleged allegiance to the Japanese Emperor because they and their families were stripped of their rights as American citizens. As I read these questions and my father’s responses to them, I was puzzled. This was not the father I knew.

On the Application for Leave Clearance, my father had listed his old friend, Susumu Watanabe, now with the 442nd in nearby Camp Shelby, Mississippi, as a reference. A short while later, the WRA sent a letter to Mr. Watanabe asking for his opinion of my father. In the carefully worded response written on March 3, Mr. Watanabe stated that he knew my father and didn’t think him a threat, but that they really needed to ask someone else for confirmation.

As the spring of 1943 wore on, my father began to worry about how his answers were being interpreted. The government had been sending other No No Boys to Tule Lake in California. He was worried that he was going to go, too. In late spring, he attempted to change his answers, but was either directed to the wrong office or misunderstood the instructions given to him by the camp administrators.

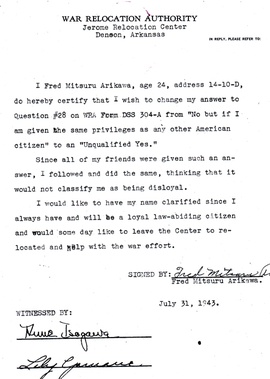

On July 31, he signed a letter formally changing his answer to question 28. It was witnessed by Anne Isogawa and Lily Yamane. In it he offered an explanation:

“Since all of my friends were given such an answer, I followed and did the same, thinking that it would not classify me as being disloyal.”

He continued to explain that he was changing his answer to yes because he wanted his name cleared and to show that he was a loyal, law-abiding citizen so that one day he could leave Jerome.

A few months later in a September 20 teletype, the acting director of the WRA, E. M. Rowalt, directed the Jerome Project Director, Paul Taylor, not to issue leave to my father and 39 other incarcerees because “[t]heir cases are still being considered by the Washington office.”

On October 20, Runo E. Arne, chief of community management, conducted the Leave Clearance Hearing interview of my father. Arne asked about my father’s political and religious affiliations as well as his sports preferences. From what I can gather from the transcripts of other interviews I have read, the government had a suspicion that prisoners who were Buddhists, participated in Judo, Kendo, or read Japanese language publications, were particular security risks.

Asked why he answered no to question 27, my father said:

“If I volunteered it is no use. My body is no good.”

When asked for his draft card by Mr. Arne, my father produced it showing that he had been declared 4F.

As for his answer to question 28, my father said,

“That is how my friend told me. I think it over, that is no good so I changed it.”

Later in the interview in response to further questioning about why he changed his answer, he said,

“All my friends, they went to Tule.”

He had made new friends in a strange land and now they were taken away.

Mr. Arne ended the interview with a statement: “If you could secure any letters from any Caucasian who knows you it might be helpful. We could attach such letters to material to Washington.”

On the same day as the interview, Dr. Kikuo Taira, one of the camp doctors from Fresno and who became our family doctor after the War, wrote a letter to support my father’s early release from Jerome.

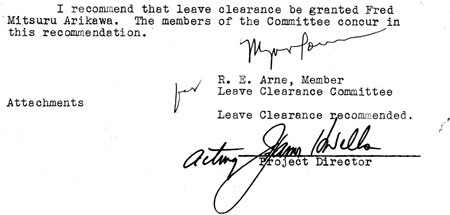

A couple of weeks later, Mr. Arne and the full Leave Clearance Committee recommended that my father receive leave clearance.

In the final Leave Clearance memorandum, it was noted that my father “claim[ed] to be physically handicapped” without mention of his draft registration and designation as 4F. Dated November 9, that final memorandum was signed by the acting project director, James H. Wells, and sent to Washington.

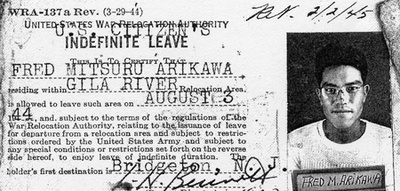

It was several months later in January 1944 before he was officially granted leave clearance by the WRA in Washington because he had no “indication of Japanese sympathies” and wanted “to live in the United States because he prefers the freedom possible” here.

More months passed and at the end of July 1944, he finally was offered employment with Seabrook Farms in Bridgeton, New Jersey for a trial period of seven months to begin on August 3. By this time, Jerome had closed and my father, grandfather, aunt, and her family had transferred to Gila River in Arizona. That trip to New Jersey was the beginning of travels that would take him to the East Coast, back to Gila River, and to Albuquerque, New Mexico before eventually returning to Fresno.

There will always be much that I don’t know about my father’s life. But these documents allowed me to paint a picture of a young Fred, citizen of a strange land, confused, and maybe more than a little bit afraid of what the future might hold.

If you want to do your own research of the WWII incarceration and internment of Americans of Japanese descent, the National Archives provides an introduction into the available records at: www.archives.gov/research/japanese-americans.

@ 2013 Ben Arikawa