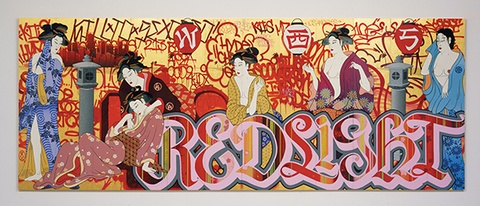

Five Japanese courtesans, their kimono sliding unashamedly off their shoulders in the heat, look on in alarm at their companion who has collapsed on the floor. Beside them are stone and paper lanterns and at the far left, the Downtown Los Angeles skyline looms amidst fiery red graffiti that almost entirely covers the lavish gold ground of the 12-panel screen. The fallen courtesan finds some support from a wall of Gothic letters forming the words “Red Light.”

This iconic painting Red Light District (2005) graphically merges the subcultures of two vibrant cities—the licensed pleasure quarters of pre-modern Tokyo (then called Edo) and contemporary Los Angeles—East LA to be more precise. These are the two cultural and artistic worlds of Gajin Fujita, a Japanese American artist who has gained international acclaim for his dramatic paintings that blend the graffiti and hip-hop style that he grew up with in East LA and Japanese artistic traditions such as ukiyo-e that form part of his family’s cultural legacy.

Red Light District (2005), Gold leaf, white gold leaf, paint markers, spray paint acrylic and Mean Streak on wood panels, 72 x 192 inches (12 panels), Private collection, Image Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA, copyright Gajin Fujita

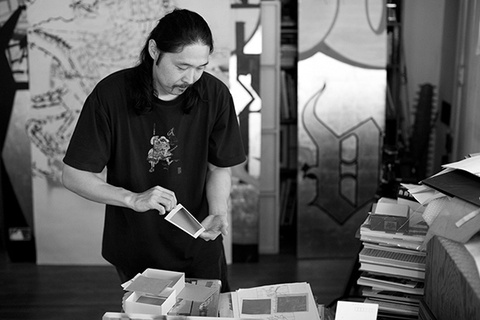

Fujita was born in Boyle Heights in 1972, the son of Japanese immigrant parents, his father an abstract landscape painter from Hokkaido and his mother a Japanese art conservator from Tokyo. At home, he spoke Japanese, ate Japanese food and eagerly absorbed the tales his father recounted of samurai heroes and fierce demons. Outside was a mostly Latino neighborhood, where he and his friends embraced West Coast hip-hop and formed the KIIS (Kill to Succeed) graffiti crew. Recognizing his artistic talent and hoping to broaden his horizons, his parents sent him across LA to Fairfax High School, a visual arts magnet. While on the bus, Fujita caught sight of spectacular graffiti and placas, or letter designs, adorning buildings across the city; he also met some of the graffiti crew members who created them and learned some of their styles and techniques. This encounter taught him that graffiti could be a true art form.

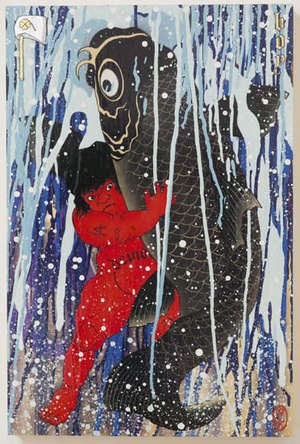

Golden Boy After Kuniyoshi (2011), Golf leaf, platinum leaf, silver leaf, spray paint and paint markers on wood panel, 24 x 16 inches, Collection of Jim Kenyon. Image courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA, copyright Gajin Fujita

After high school, he went on to East LA College and then Otis College of Art and Design. There, his professor, Scott Grieger, noticed his unusual attention to detail and strong artistic discipline and encouraged him to go to graduate school at University of Nevada, Las Vegas, where he studied Renaissance painting and was advised by art critic and professor, Dave Hickey. Hickey saw in him a “kind of classic impure style” and chose him as the youngest artist in the Santa Fe Biennial in 2001.

According to Fujita, Hickey taught him that “fine artists should always try to violate people’s expectations.” This idea sparked an epiphany for Fujita. He started with Japanese erotic prints called shunga, some of most graphically detailed erotica produced anywhere, and thought, “This would look really raw and gritty if I were to layer it with graffiti.” The result was the painting Motel (2001), his first work that juxtaposed bold imagery, styles and techniques from both his cultural backgrounds.

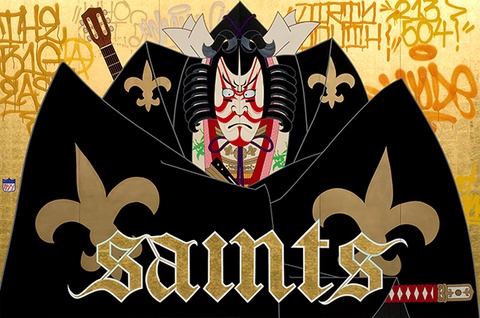

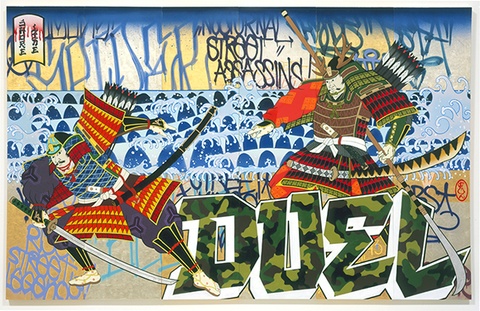

Since then, Fujita, has combined samurai, dragons, courtesans, Japanese textile patterns and gold leaf with cholo-style tagging, Old English lettering, Old Western hip-hop writing, American sports logos, spray paint and markers, often on a traditional Japanese multi-paneled screen format. Works such as Golden Boy After Kuniyoshi (2011), in which Kintaro, a boy with super powers from Japanese folk legends, sports an LA Dodgers tattoo on his arm, playfully draw together his two worlds in one bold image. Others works make bolder social connections. According to Fujita, in Red Light District (2005), mentioned above, the burning silhouette of Downtown LA and the heat suggested by the loose kimonos and fierce red graffiti refer to the fires of the 1992 LA riots. Similarly, Shore Line Duel (2004), in which two exquisitely detailed samurai warriors battling on a beach, presumably here in Southern California, with the words “Nocturnal Street Assassins” hanging over the horizon, connects two fighting traditions—the mighty warriors of old Japan with the street gangs of his childhood neighborhood.

Shore Line Duel (2004) Gold leaf, white gold leaf, acrylic, spray paint and Mean Streak on wood panels, 60 x 95 1/8 inches (6 panels), Collection of Vicki and Kent Logan, Image courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA, copyright Gajin Fujita

The spray paint, graffiti, and references to gang fighting are all aspects of a Los Angeles subculture, one generally considered defiant and dangerous. What may not be as immediately obvious to a Western audience is that many of the Japanese visual elements—the samurai, courtesans, demon figures—are borrowed from a similar Japanese urban subculture—the “floating world,” or pleasure quarters of pre-modern Tokyo (Edo). Although this zone was licensed by the government, it was still a place where the people could defy the country’s rigid social hierarchy, break many daytime rules and mock the shogun. Not surprisingly, the quarters swarmed with government spies.

It was in this nighttime world of theaters, tea houses and brothels that the artistic tradition of ukiyo-e (“pictures of the floating world”) evolved. Designed by top artists like Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1862), these pictures depicted (and often advertised) the inhabitants of this nocturnal realm—the courtesans, musicians, waitresses, prostitutes and kabuki actors—as well as legendary heroes, demons, battle scenes and landscapes. Woodblock prints were most popular format for these images, since they were mass-produced and sold for the price of a bowl of noodles, and, of course, the erotic prints, or shunga, were best sellers, as were the designs that cleverly mocked the regime. They had to be very subtle in this. Government censors regularly checked them for seditious content, and some artists were arrested for suspected political satire. These ukiyo-e prints, though often marvels of design and hugely popular in their time, were not considered art and were often thrown away, like today’s movie posters.

Fujita grew up aware of this floating world, and when, in 2001, when he first tapped into it, he claims that he felt like he’d “cracked something.” From then on, his intent has been to take various characters from that world and “relocate them throughout history and place them in a contemporary urban society like LA.” The result is something that could only have been created here and now. “I look at my paintings as American,” he explains, “because of the meshing of Japanese and Californian ideas. They are totally Los Angeles paintings.”

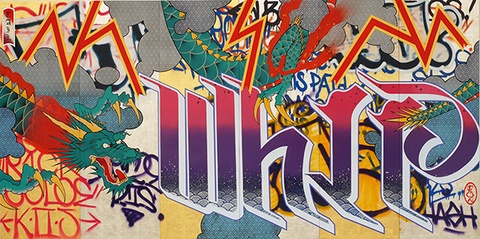

Tail Whip (2007), Gold leaf, silver leaf, acrylic, paint markers, spray pain and Mean Streak on wood panels, 48 x 96 inches (6 panels), Collection of James Yohe, Image courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA, copyright Gajin Fujita

Trance, 2002, spray paint, acrylic & white gold leaf on wood panels, 8 x 20 in. (20.3 x 50.8 cm) (diptych), Private collection, Los Angeles, CA, Image courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA, copyright Gajin Fujita

* This was an article in the “Japanese Accents” series showcasing Southern California artists whose works integrate elements of Japanese art and design, yet speak boldly about our contemporary SoCal lives. Some are Japanese American; others have no blood connection with Japan but have discovered something Japanese that resonates with their artistic vision. It was originally published on KCET Artbound on September 13, 2012.

© 2012 Meher McArthur / KCET