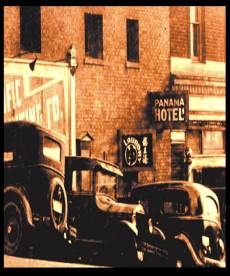

Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet is a historical fiction novel about a little love story between a Chinese boy and Japanese girl during the 1940’s Japanese internment of WWII based in Seattle, Washington. As you can imagine, it’s a popular choice for book clubs where I live because you can actually visit the places mentioned in the book, especially the Panama Hotel on 605½ Main Street, Seattle, WA. Yes, it really has a ½ in the address! Today, the Panama Hotel is a Bed and Breakfast, has a lovely tea house and has become a bit of a tourist attraction for those who have read the book. You can visit their website to see more: www.panamahotel.net

My post is not about this fiction book, but about a true story about the man who actually owned and ran the Panama Hotel from 1938 to 1986. Today, Mr. Takashi Hori, a 93 years old nisei, (nisei means a second generation Japanese American) is a spry man with a very sharp mind and amazing memory. He is my friend that I have come to know over the past few years through a club I belong to, the Hyakudo Kai, which originated in Hiroshima, Japan. The literal translation of this club is Work Until 100 Club, but it really means, Let’s Keep Active Until 100 Club! I am their youngest member in Seattle.

Growing up in the center of Japantown in Seattle, has given Mr. Hori a unique life experience. His stories of life before, during and after WWII deepened my understanding of the Japanese who emigrated to the U. S. during that time. Although I am Japanese-American, I was very ignorant about the internment camps of the Japanese Americans during WWII. Being from Honolulu, I have no family that was interned. Since moving to the Greater Seattle area ten years ago, I have learned much more on what the Japanese Americans went through during that period through those who were interned. There are many hidden sufferings and repercussions of how it influenced each and every person. No two stories are the same. And in my narrow knowledge are glimpses on how these experiences have silently translated into the next generations. Mr. Hori has opened my eyes to a world I knew nothing about. He captured my curiosity and attention and we have spent hours of enjoyable conversations over lunch and tea.

Through his life experiences, we can learn so much of the unspoken and unknown history that the older Japanese generations kept to themselves. They didn’t speak about it because the Japanese custom is that way; there are certain things we are not supposed to say in public. That’s just the way it was and to some extent, still is. I find Mr. Hori’s life so fascinating and I am grateful that he shared his life experiences with me, broadening my appreciation for the many generations of immigrants that took the courage to find a life away from home.

Mr. Takashi Hori and the Panama Hotel, a Nisei Story

Sanjiro Hori, Takashi’s father, born November 24, 1875 in Kumamoto Prefecture was the second born son. In Japan, traditionally, the first son inherits the family home, land, business and responsibilities. As the second son, he understood his position and had to find a way to earn enough money to buy land to build a home and start a family. Today, it may sound harsh and unfair to the other siblings, but that’s just the way it was, no questions were asked—it was just accepted as a part of life in Japan. Some families still practice these traditions. As an Asian, we understand, though we may not totally agree, because that’s just part of our tradition.

There is a word in Japanese, dekasegi, which means working away from home to earn a wage. Sanjiro Hori first left home for Hawaii, his first dekasegi trip, and managed to earn enough for a plot of land back home. For reasons unknown, he decided to leave home once again and headed for San Francisco for his next dekasegi trip. The year was 1906. The ship he set sail on suddenly had to change direction when a major earthquake struck San Francisco and he ended up in Seattle. Such is fate.

As a young single man, there were various labor jobs available to the Japanese in the area. They worked the lumber mills, the Alaska salmon canneries, can producing factories (he said they had to make the cans as not all of them were automated in those days), railroads, farms and other forms of labor intensive work.

Sanjiro worked in the saw mills for many years, managed to find a Japanese bride along the way and start a family. Because of an injury of a broken leg, he headed to Seattle’s Japantown with his family to recuperate.

Back in those days, there was a thriving Japantown that was just like Japan in many ways. There was no need to speak English because everyone and everything was Japanese. Their town was self-sufficient, with their own doctors, midwives, dentists, bath houses, restaurants, clothing shops, grocery shops, hardware stores, laundry shops and everything needed for their lives.

The architecture was simple board and batten wood and brick, most were rectangular in shape, similar to many small towns in America. The difference was mainly business signage, which was in both English and Japanese. By that era, the Japanese people residing there didn’t wear kimonos, they had western clothes; the men wore shirts and slacks, the women wore dresses. On the outside it was very westernized, but inside it was all Japan.

According to Mr. Hori, most young single men from Japan (he said 98%) wanted to make a buck and go home. America was just a place for opportunity to save enough money for a more comfortable life in Japan. That was their intention, but it didn’t always turn out that way. The biggest factor in their change of attitude was the children. These children, who were born in American and attended American schools had become American. This was home to them, as most of them had never been to Japan.

Life was transient in those days, as much of the work was seasonal. After collecting their earnings they would head back down to Japantown in Seattle and stay in the many small hotels. Today, these hotels are what we would consider a guest or boarding house. Their living quarters were simple rooms, with a wood floor, one window and a single bed. If you were lucky you had a closet and sink in your room, but with only a few possessions, this wasn’t much of a concern for these men. The slightly larger rooms were eventually occupied by families with children. Down the hall were the restrooms and showers but many preferred to bathe at the local public bath houses.

Some of these hotels did have kitchens. In fact, I saw an original room at the Wing Luke Museum in Chinatown whereby this hotel had a communal kitchen and dining room. But according Mr. Hori, in Japantown, most of them didn’t provide a kitchen. Since food is such a big part of Japanese culture, I wondered where these men ate all their meals.

In those days, social lives centered around the many local Japanese diners called meshiya. Mr. Hori told me that the clientele of each meshiya reflected on the home town of the meshiya’s owners. If the owner was from Hiroshima, the clientele were from Hiroshima or nearby areas. One major reason was the difference in dialect, as they had difficulty understanding each other! Another factor was food, as seasonings and flavors can vary with regions.

In general, the food was simple, home-style Japanese cooking that included the standard rice, miso soup and an entrée such as grilled fish, sashimi, sukiyaki or nizakana (stewed fish). The menu written on a blackboard, changed daily and the owner’s hired chefs who came from their home town. Because of the lifestyle, I am assuming these meshiya had to be open all day. And although alcohol was prohibited, he said many served sake, Japanese rice wine. Since he was a child at this time, he didn’t know where it came from but he said it was always available.

While Sanjiro was recuperating in Seattle, he heard that a Kumamoto meshiya was up for sale. He and a friend took this opportunity and bought it. So, that’s how the Hori family settled in the middle of Japantown with Sanjiro running a meshiya.

This article was originally published on the Asian Lifestyle Design website on September 5, 2011.

© 2011 Jenny Nakao Hones