Thanksgiving is the quintessential American holiday, but, as a young Sansei, I didn’t believe there was any connection between my Japanese family and the Mayflower pilgrims who colonized New England.

I grew up in the West in the 1960s and ’70s, often in towns without much diversity, where I didn’t feel very pilgrim-like or “American,” that is, Caucasian. I secretly longed to wear the pilgrim’s black dress and white apron with ringlets under my bonnet. Instead, looking more like Squanto and Pocahontas, I was cast as the noble “Indian” in school pageants—wearing my long hair in two braids, with a stereotypical feathered headband, moccasins and a brown fringed dress sewn by my mother. Yet, as different as I often felt at school, I found comfort at my family’s multi-ethnic Thanksgiving table. I didn’t know it then, but my journey toward understanding my own pilgrim heritage would begin here.

As a youngster, I never thought much about which dishes were American and which were Japanese. Our holiday celebration included turkey, mashed potatoes, marshmallow yams, lime jello, gohan, cranberries, wontons, tsukemono with shoyu, pumpkin pie and, my favorite, stuffing. My mother called the dish “Grandpa Tanaka’s Stuffing,” so I thought it was from an old recipe her father brought from Japan. Grandpa passed away before I was born so he was a mystery to me.

I was introduced to Grandpa’s Stuffing in Colorado where I lived until I was eight years old. The evening before Thanksgiving, my mother and her visiting family would gather in the kitchen to cook. Mom chopped onions while her sisters, Auntie Yoshiye and Auntie Trudy, diced celery and grated carrots. My little brother Davey and I sat at the kitchen table with Grandma Tanaka and day-old Wonder Bread, tearing slices into bite-size pieces. Davey inevitably stuffed his cheeks with bread and Grandma predictably giggled.

Soon we’d hear the sizzle of bacon in the cast iron skillet. Mom stirred in the vegetables and I seasoned with salt, pepper and sage. Davey added bread bit by bit. The aroma of Thanksgiving filled the kitchen as Mom emptied batches into the speckled black roasting pan, giving me a chawan of stuffing to taste with my pink hashi.

At dinner, the turkey and stuffing emerged—our ingredients transformed into a toasty delight. As we joined hands, we lifted a prayer of thanks and remembered those who were no longer with us.

***

As I grew older and learned about traditional pilgrim dishes, I realized that stuffing wasn’t Japanese fare. So, how did Grandpa learn to make stuffing? My mother said an American family taught him. That satisfied me for many years but, after my mother’s passing, I began to wonder again. Auntie Yoshiye opened my eyes.

Grandpa—Chojiro Tanaka—left Yokohama, Japan in 1897, at age 13 when his widowed mother passed away. An orphan, he headed for America on a steamer to join his 18-year old brother, who paid his passage. With nothing in his pockets except the name of his brother, he survived the three-month voyage with leftovers and care from the ship’s galley crew.

Chojiro docked in Vancouver, British Columbia and found his way to Idaho Falls, Idaho where his brother worked as a cook’s assistant on the railroad. Too young to live in railroad housing and with nowhere to go, Chojiro was taken in by an American family as a houseboy. The family nicknamed him “Charley” and arranged for him to go to school. He started the first grade at 13 and completed 6th grade, learning how to read, write, and speak English, invaluable skills for an immigrant. He helped in the family’s grocery and dry goods store on weekends, hoping to own his own shop one day. This family taught Charley about Thanksgiving and giving thanks to God—and how to make stuffing.

As a young man, Charley moved to Utah and managed a pool hall and cafe with his brother. He returned to Yokohama in his 30s. It was arranged for him to meet and marry a 21-year old seamstress named Rikiko Kodama, who wished to come to America to be near her brother. The couple arrived in 1919, settling in Kemmerer, a small coal mining town in southwest Wyoming. My mother, Chiyoko, was the youngest of their five children.

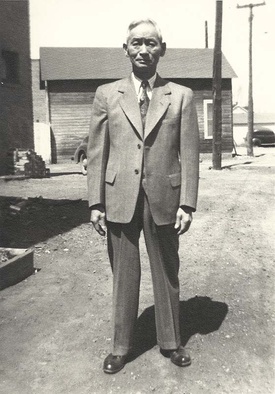

Chojiro “Charley” Tanaka in Kemmerer, WY, wearing one of his made-to-measure suits (1940’s family photo)

As my mother used to say, her family “barely eked out a living” during the Depression and War years. She often went to bed hungry. Charley first supported his family as a traveling salesman, riding the Union Pacific from town to town in Idaho and Wyoming peddling suits, yard goods, and sewing notions. He realized his dream when the Tanaka Tailor Shop opened in the 1920s, near the first J.C. Penney store. Charley sold western wear and made-to-measure suits. Rikiko sewed, babysat, gave shamisen music lessons, and taught townsfolk how to make paper flowers to brighten the bleak Wyoming winters.

The family ate from their garden and shared meager dinners of gohan and okazu, stretching three pork chops to feed seven people, with occasional sage chicken, rabbit, deer, and trout from the nearby hills and streams.

But Thanksgiving was a time to feast. Every Thanksgiving and Christmas, the Tanakas received a turkey—precious to this modest family—as a gift from the town doctor, who had delivered the five Tanaka children in their home. The turkeys always arrived, even during World War II when other Japanese Americans were imprisoned a few hundred miles away in Heart Mountain, Wyoming.

In their spare living quarters behind the storefront, Charley prepared the turkey with his houseboy stuffing. Before the meal, Rikiko placed a small offering of rice and stuffing at the Japanese altar. Then, with the family gathered at the table, Charley stood, lifted his chawan in both hands to his face, bowed his head in silence, and whispered, “Arigato.”

***

My mother carried on the tradition of Grandpa’s Stuffing, teaching me when I cooked my first Thanksgiving dinner in my college apartment. Today, I live in Los Angeles, blessed with a comfortable suburban life with my Irish-American husband and our two daughters, immigrants who came to America from China through adoption.

On Thanksgiving eve, as my family cooks Grandpa’s Stuffing and volunteers at church to prepare dinners for needy families, I reflect with gratitude on my humble but solid roots. Although my grandparents traveled by ship across the Pacific and not the Atlantic, and landed in the Rocky Mountains not Plymouth Rock, they too journeyed to this new land with courage and hope, planting roots in the frontier, where they were greeted with God’s grace and the blessings of hospitality when they needed it the most.

My children also arrived in America with our hopeful promise. In the 21st Century, my Chinese daughters had the option to choose which multi-ethnic Americans to be in their school productions, as it should be. At our Thanksgiving table, we recognize that the dish that best reflects our family heritage is not gohan, gyoza or jiaozi dumplings, it’s Grandpa Tanaka’s Stuffing. Together, we join hands, bow and give thanks for our pilgrim heritage and our very American family. Arigato ojiisan.

© 2012 Jeri Okamoto Floyd