When Bill Sueoka arrived at the dusty, desolate former Japanese internment camp in Granada, Colorado, where he and his family were imprisoned for nearly three years during World War II, he didn’t carry the typical mental burdens of a former inmate.

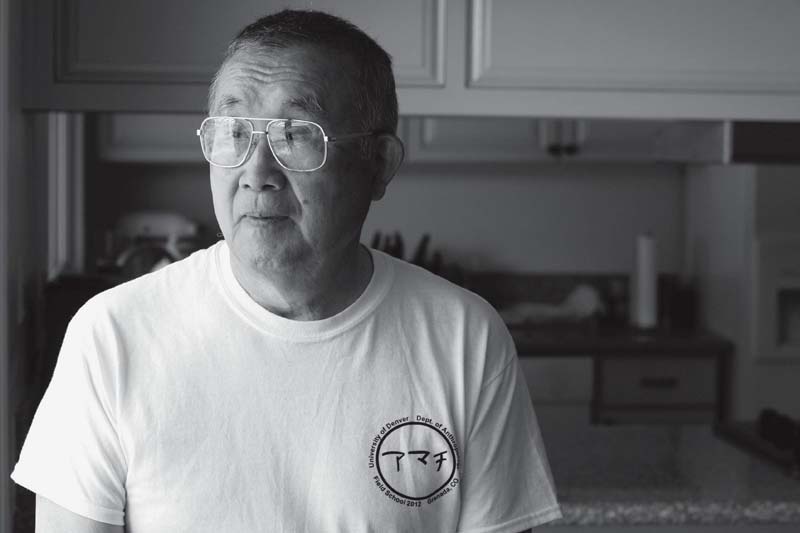

Sueoka, who takes archeology classes at Moorpark College, participated in an excavation of the site hosted by the University of Denver.

“I had a good time because I was really young. I didn’t know any better. My parents didn’t tell me it was a bad experience,” Sueoka, who traveled there with his son Michael, told the Acorn on the third day of his week-long dig that ended this week. “Our civil rights were trampled, but nobody taught me to be bitter.”

The Thousand Oaks resident, 74, was 4 years old when his parents were forced out of their home in Petaluma and took their two young children to the Amache camp, one of 10 relocation centers set up by the federal government after Japan bombed U.S. naval base Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on Dec. 7, 1941.

Two months later, on Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. The order forced about 120,000 people of Japanese descent in the United States into the camps because the government feared they would act as spies for Japan.

The majority of prisoners in the camps were U.S. citizens. Half of them were children.

In the fall of 1942, the Sueoka family brought only what they could carry to the prison where they lived for nearly three years. They left their rented home, their poultry farm and the personal possessions that didn’t fit in their arms.

Sueoka, a fourth-generation American, remembers little from that time. But old objects found beneath the dry earth at the National Historic Landmark triggered memories of happy days he spent playing with other children. The excavation group that included a Denver professor and college students were in the field by 6 a.m. When he found a marble, Sueoka got down on his hands and knees and rolled it across the dirt like he did when he was a child. When he saw coal residue on the ground, he recalled tossing the black lumps to entertain himself.

A rusty tin can sat for decades on the barren plain.

“I instantly recognized the Log Cabin syrup can. That memory came back to me in a flash,” Sueoka said.

Standing in the doorway of the barracks where he slept with about 7,000 other prisoners, he remembered how his parents sheltered him and his younger sister from worry and fear.

“It was a reflective moment but I didn’t have strong reactions to it,” Sueoka said of the visit.

What surprised him was the isolated desert where temperatures reach hot and cold extremes.

“Emotionally you realize it’s really a remote place,” he said.

From his late mother’s written recollections of the prison, “I found out how tough it was,” Sueoka said.

Michael, whose mother is Mexican, noted that his father’s report cards from the camp tracked his progress in becoming “Americanized.” An early report said, “Bill is still speaking Japanese.”

“I’m not angry,” Michael said about the injustice his family endured. “The point is that it doesn’t happen again to anyone.”

Sueoka said his parents embraced the Japanese saying “shikata ga nai,” meaning “it can’t be helped,” until the family returned to Petaluma and reopened their poultry business before the war ended in 1945. Years later, in 1968, Sueoka served as a pathologist in Vietnam during the war.

“In Japanese culture people proceed with life in the face of catastrophes,” he said. “You make the best of a situation and go on with life.”

It’s a legacy of tenacity and forgiveness that Sueoka, who has five children and four grandchildren, carries with him.

“From my point of view this is the best country. My family felt the same way,” he said. “I’ve lived a very good life because I live in the United States.”

* This article was originally published in the Acorn Newspaper, www.theacorn.com (July 19, 2012).

© 2012 Anna Bitong