>> Read part 7

Six months after it was transferred to the WRA, Manzanar experienced a revolt that ended in the death of two innocent young men and shook the confidence of the administration and inmates alike. At 8 PM on 5 December 1942, six masked men entered the apartment of a Nisei, Fred Tayama, and assaulted him with clubs. Tayama was widely despised as an aggressive opportunist. In the decade before the war, his chain of restaurants was known for their poor working conditions and low wages. He was also co-owner of a company that charged Issei exorbitant fees for services such as filing alien travel permits and transferring business licenses. His reputation followed him to Manzanar, where he had recently incensed the Nikkei by having claimed himself as their representative at a Salt Lake City meeting of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL)—an organization that was formed in 1929 to promote the American identity of the Nisei.1

Tayama named Harry Ueno as one of his assailants. Ueno, a popular man who was a chief cook of one of the mess halls and the head of the Kitchen Workers Union, was removed from the camp and jailed in the nearby town of Independence. It was his arrest that triggered the mass meeting described at the beginning of this essay.

Kurihara and the crowd protesting Ueno’s arrest believed that charges that Ueno had made earlier—that two administrators had stolen sugar and meat meant for the inmates—made him the target of camp authorities, and that they used the beatings as a way to remove him from the camp. Thinking that Ueno was wrongly imprisoned, Kurihara and other speakers that afternoon objected vociferously to his arrest and demanded his release.2

It was agreed that a Committee of Five composed of Kurihara and four other men would negotiate the release of Ueno. Because of his fearlessness in speaking his mind, Kurihara was selected as spokesperson of the committee.3

With the crowd marching behind them, the Committee proceeded to the administration building, where they met with the Manzanar Project Director Ralph Merritt and demanded the release of Ueno. After an hour of back-and-forth talk, interspersed with taunts and jeering from the crowd, Merritt realized that he needed to respond positively to what had become a volatile situation, especially since investigations into Tayama’s beating had brought no evidence that Ueno was among the assailants. Moreover, the Committee of Five had told him that it could not control the crowd, and urged him to concede before some tragedy occurred. After some discussion Merritt agreed to have Ueno transferred to the Manzanar jail.

That evening, as a growing mass of people formed near the jail and demanded Ueno’s release, the military police was called in to help. As the night wore on, the crowd’s temper became increasingly menacing: some in the crowd taunted and jeered the soldiers, some sang Japanese patriotic songs, and some threw stones, sand, bottles, and lighted cigarettes. After making several attempts to convince the crowd to break up, the Military Police Captain Martyn Hall decided that the only way to disperse the crowd was to have soldiers fire tear gas grenades. In the ensuing smoke, panic, and confusion, two soldiers shot into the crowd, killing two young Nikkei men.4

This tragedy ended the Manzanar revolt. Japanese Americans who had collaborated with camp administrators and whose names were on a death list created by angry protesters were whisked out of Manzanar and eventually relocated to Chicago and other cities, while Kurihara and his fellow committee members were jailed in Bishop, a town fifty miles north of Manzanar. Later they were taken to an isolation camp at Moab, Utah, created for so-called citizen troublemakers from all the camps, none of whom were formally charged (figure 5).

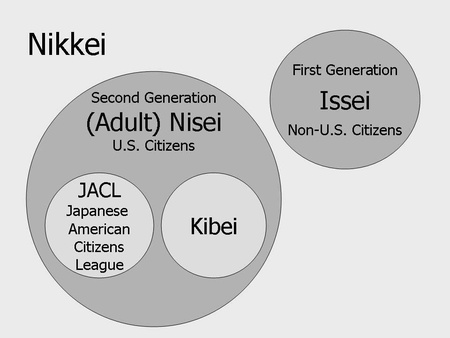

Figure 5. Among the Nikkei—ethnic Japanese—were the Issei, the first generation who were not U.S. citizens. In 1922 a U.S. Supreme Court decision denied them the right to become naturalized. Their children were the Nisei, born in the United States and therefore U.S. citizens. In the camps, many were minors. Among those who were adults were members of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), Nisei who cooperated and collaborated with camp administrators. Then there were the Kibei, those who were born in the United States and who were sent to Japan in their youth and subsequently returned to the United States. Most of the Nisei were not part of either of these two groups. Some Nisei sympathized with the JACLers, but in time, more and more Nisei sympathized with the views of the Issei and Kibei.

The Manzanar revolt was the culmination of months of humiliation, frustration, and conflict not only between inmates and camp officials, but also among the inmates themselves. At the core of the conflict were two fundamental “cultural themes” that governed the Nikkei community in the decades before the war. The first was the importance of social hierarchy based on age, generation, and sex. Based on this hierarchy, leadership roles and power in family and community life went to older men and Issei parents. The second cultural theme emphasized group solidarity over individual interests. These two themes were central to the world view of the Issei and the Kibei—those Nisei who, although born in the United States, spent part of their young lives in Japan and who received at least part of their education there. The non-Kibei Nisei, who had greater contact with the larger American society, shared this cultural perspective, but to a lesser extent.5

Among the Nisei were JACL leaders, who enthusiastically internalized what they believed were American attitudes and values. Thus they tended to distance themselves from notions of Japanese social hierarchy and ethnic group solidarity. So while the Issei and Kibei gravitated together in the face of harassments and discrimination, the JACLers “advertised their Americanism.”6

Although Kurihara had shared the JACL enthusiasm for being an American patriot during the decades before Pearl Harbor (he was a member of the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars), his reaction to the forced removal and incarceration of the Nikkei separated him from the JACL. While the JACLers accepted their incarceration as unavoidable, Kurihara vigorously protested their acquiescence and compliance. In contrast to the JACLers, Kurihara believed that Americanism meant standing up for one’s rights and resisting the abuses of those in power.7

In the months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Tayama and other JACL leaders sought to demonstrate their loyalty to the United States by reporting to the FBI suspicious activities among the Issei, provoking antipathy from the Nikkei population. “Issei, Kibei, and Nisei generally believed that [the JACL] was sacrificing the community’s welfare for its own aggrandizement.”8

Hostility toward the JACLers and differences in world views concerning social hierarchy and group solidarity underlay the emotional turmoil in Manzanar. This turmoil, in turn, lay at the heart of the education of Manzanar’s adult Nikkei.

In Exile Within, Thomas James provides a detailed analysis of schooling in the camps. WRA educational planners, with the guidance of Paul R. Hanna of Stanford University, envisioned a curriculum that integrated school and community life, and the schooling of youth who would learn about and practice democracy. The disjuncture of such a vision with reality was evident to many educators, particularly those who taught the students, both of whom saw plainly the guard towers and barbed wire fencing outside their classroom windows.9

Notes:

1. For an excellent analysis of the revolt, see Hansen and Hacker, “The Manzanar Riot: An Ethnic Perspective.” The authors argue persuasively that “revolt” is a more appropriate word than “riot” to describe what happened. For detailed information on the revolt, see Unrau, The Evacuation and Relocation, 477-523; and Manzanar-Incident Material, Box 69, Entry 4b, RG 210, Records of the War Relocation Authority, National Archives, Washington, DC. A detailed portrait of Tayama is in Togo Tanaka, “A Report on the Manzanar Riot of Sunday December 6, 1942,” [7 January 1943], pp 1-13, O10.12, 67/14c, JAERR.

2. Koichi Tsuji, “A Private Report on the Incident of Dec. 6, 1942, Part I,” [6 December 1942], S1.20c, 67/14c, JAERR.

3. Unrau, The Evacuation and Relocation, 480.

4. The two soldiers later testified that they believed that their lives were in danger, and the military Board of Officers who heard their case concluded that there was no wrongdoing. However, at later hearings of a subcommittee of the Senate Committee of Military Affairs, Captain Hall admitted that two rounds of tear gas thrown into the crowd broke it up before the shots were fired, questioning the claim that the soldiers were in physical danger. See Unrau, The Evacuation and Relocation, 519-21.

5. For an analysis of the central role of these two cultural themes in the Manzanar revolt, see Hansen and Hacker, “The Manzanar Riot,” 121.

6. Hansen and Hacker, “The Manzanar Riot,” 124. Much has been written about the JACL. See, for example, Roger Daniels, “The Japanese,” in John Higham, ed., Ethnic Leadership in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978), 36-63; Paul R. Spickard, “The Nisei Assume Power: The Japanese (American) Citizens League, 1941-42,” Pacific Historical Review 52 (1983), 147-74; Yuji Ichioka, Before Internment, 46-47.

7. For Kurihara’s membership in the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, see FBI report, Kurihara et al., Internal Security-Sedition-Public Law 503, 13 September 1942, pp. 25-26, Assistant Secretary of War 020, Civil Affairs Division, Box 9, Entry 47, RG 107, Office of the Secretary of War, National Archives, Washington, DC.

8. Hansen and Hacker, “The Manzanar Riot,” 124-25.

9. Thomas James, Exile Within: The Schooling of Japanese Americans 1942-1945 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987), 37-40, 52-54. For a striking contrast between the planned curriculum for the schools and the reality of camp life, see Thomas James, “The Education of Japanese Americans at Tule Lake,” Pacific Historical Review 56:1 (Feb. 1987): 25-58.

* This essay was the History of Education Society Presidential Address delivered at the annual meeting in Philadelphia, October 2009 and published in History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 50, No.1 (January 2010).

** The definitive version is available at www.blackwell-synergy.com.

© 2010 The History of Education Society