“They came here to be American.”

—Earl Hanson

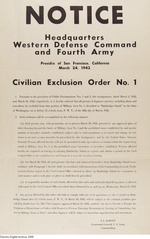

As we trace the calendar of Japanese American history through the images and words preserved in Densho’s Digital Archive, we come upon dismaying news photos dated March 30, 1942. On that day, the first Japanese American families were taken from their homes by armed soldiers under the authority granted by President Roosevelt to Western Command General John L. DeWitt.The general had won the cabinet-level argument in favor of removing every man, woman, and child of Japanese descent from declared military zones of the West Coast. Up and down the coast, stunned Japanese American communities were paralyzed by curfews, frozen bank accounts, and the arrest of their community leaders. Then on March 24, General DeWitt’s Civilian Exclusion Order No. 1 appeared on public walls and telephone poles of a small island in the Pacific Northwest.

Bainbridge Island, Washington, is situated a short ferry ride from Seattle, near naval bases and shipyards considered vulnerable to Japanese attack. Bainbridge was also home to over 200 Japanese immigrants and their children. The Issei had built successful farms, nurseries, markets, and shops. Civilian Exclusion Order No. 1, like the 98 that followed, gave Japanese Americans six days to sell or entrust to others everything they had earned in a lifetime of work.

The exclusion order applies the benign euphemism “evacuation” to the forced removal, as if the island’s Japanese Americans were being rescued from a natural disaster. On March 30, “all persons of Japanese ancestry, including aliens and non-aliens” (in other words, citizens) were ordered to report “for evacuation in such manner and to such place or places as shall then be prescribed.” Destination unknown, return date unspecified.

The more accurate term “exclusion” of the order’s title evoked the Japanese Exclusion League (formerly Asiatic Exclusion League), formed in California by labor and farm groups in 1905. The California league, and its chapters in other West Coast states, had the stated aim of eliminating economic competition and social contamination from Asian “brown men.” The anti-Japanese forces successfully pressed for alien land laws and an end to immigration from Japan. A typical anti-Japanese article published by the San Francisco Chronicle in 1905 warns of a “peaceful invasion…worse than war,” saying, “the Japanese in America considers himself as engaged in an economic war, and his ethics are those of the battlefield.” In the name of national security, but rooted in racism, DeWitt’s Exclusion Orders completed the banishment that the Exclusion League had sought nearly a half-century earlier.

While the other West Coast states followed California’s lead in passing anti-Asian laws, the small Northwest community of Bainbridge Island escaped the most virulent racism. In his interview for Densho, Earl Hanson, the son of Norwegian immigrants, recalls growing up with Japanese American families. As a boy, he picked strawberries for the Sakumas and Okazakis. When asked if he thought his neighbors planned to go back to Japan, Hanson replied, “No, they came to be American, Americans. And they all stayed.” He fondly describes the “good, good guys” at Bainbridge High School: Jerry Nakata and Mitsu “Lefty” Katayama were basketball stars; Harry “Bear” Koba played tackle; and Sada Omoto became class president. Kay Nakao was a “cutie.” Then came Pearl Harbor and the military order that took them all away.

March 30th, okay, yeah. But in between there, life went on as usual. And then when they announced that they were gonna take ‘em away, I think the, they gave ‘em ten days to pack up their stuff, one suitcase per person was all they could take. And those poor people had to get rid of—a lot of the people had to get rid of all their stuff. I know, I think it was Sam Nakao, was talkin’ about, they had just bought a new refrigerator and a new stove. What are you gonna do with it? Give it away, penny on a dollar? Or give it away? …

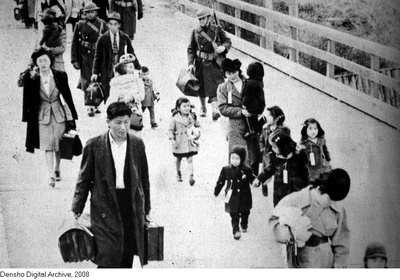

Hanson remembers soldiers putting his friends on a special ferry for Seattle. From there trains would take them deep into California to the Manzanar “assembly center.”

Well, you know, it kind of came as a shock to all of us. And when they announced that, the soldiers moved on the Island, and they were patrolling all over, and I remember that one of the arterial stops, the army truck was parked there and I talked to this guy. And I, and one of the questions I asked him was what he felt about taking our guys away. He says, “I can’t say anything because I’m in the service.” So we told him, I says, “You’re taking away our, some of our best friends.” And then when I was, went down to the Eagledale dock to see ‘em off, “Park, get up there. Up there.” And Frank Kitamoto has a picture showing, and there’s soldiers up in, up in the field up there, holding us people back up there. …Why, everybody was crying, you know. Hey, that was a shock.

In addition to the shame and stigma of being incarcerated by their own government for no crime they committed, and without due process of law, the Nisei have had to deal with a question frequently posed by outsiders, and by their own children. Kitamoto gives his opinion:

It’s interesting because people always say, why didn’t you protest, why didn’t you say you wouldn’t go and that kind of stuff. And the times were a little different in those days. I think in a lot of ways, if they protested, it might have been worse because it wasn’t, the awareness isn’t like it (is) now. You didn’t have television that would beam us across the world, or even to the rest of the nation, as far as what was going on. And it was really easy for things to happen to you and for people not to be aware of it. In fact, I think a lot of people back east never knew this even happened.

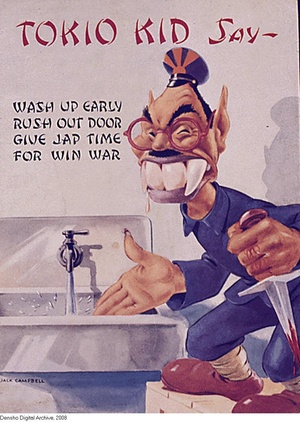

Kitamoto correctly points out the country’s ignorance. Those on the East Coast and elsewhere who, unlike Earl Hanson, never met a Japanese American person learned all they knew about the “Jap” enemy from wartime propaganda. Even some on Bainbridge Island, who did have contact with Japanese Americans, were in favor of the incarceration. Long after the war, they resented the reparations won in 1988. Remembering how his “good good” boyhood friends and their parents suffered, Hanson is quick to set them straight:

Penny on a dollar. Put it that way, ‘cause it was, lot of ‘em lost a lot of money. And, you know, in later years, when they got the $20,000, you know, after they had—well, this was just a few years ago that they got that. I heard some rebuttal on that, and I told ‘em, I says, “Did you ever grow up with ‘em? Did you ever know any of ‘em?” “No.” I says, “Don’t make statements like that.” Like I says, “If you had to leave your home and everything in it, or get rid of it right now, what would you do?” I says, “That was the situation that a lot of them were in.”

* This article was originally published on Denshō: The Japanese American Legacy Project.

© 2008 Densho