Shigekata Murao is pacing around his room in the most expensive inn in Chiran, the town where he grew up. He has proudly returned home to take a bride. But matters are more complicated than expected.

His older sister has hidden the letters he wrote about his success in Seattle from his family. And while he is respected in the village for having forged his own way, the townspeople are not eager to send their daughters off to America.

* * *

How did a Japanese nisei from a traditional family end up at the epicenter of the San Francisco Beat scene? In a sense, Shigeyoshi (“Shig”) Murao was following in his father’s footsteps: if he carved an identity that went against everything he had been raised to be, so too had his father.

The Murao family owned land in Chiran, a village on the southern island of Kyushu. By the time Shig’s father, Shigekata, was born in 1888, there was no longer a place in the society for samurai warriors.

Yet tradition dictated that samurai have no trade; and as the family held to the tradition, they had been forced to sell off much of their land to survive even before Shigekata was born.

When he came of age, Shigekata made a bold move and went to business school. Then, over the family’s objections, he immigrated to Vancouver in 1910 and found work in restaurants as a dishwasher, busboy, and cook.

Shig’s father had not intended to stay abroad, but he learned to cut meat through his restaurant work. After a time, he moved to Seattle, where he opened a butcher shop called Annex Meats.

The family would not learn of Shigekata’s success for some time, because his older sister, embarrassed by his work handling meat—a task not considered proper for a samurai—hid his letters from his parents and the rest of the family.

In 1920, his business prospering, Shigekata returned to Chiran, took a room at the most expensive inn in the village, and announced his intention to take a bride. But the townspeople were not eager to send a daughter off to America and perhaps never see her again.

Shigekata found his bride through an arranged marriage to an orphan named Ume Sata, who was from a prominent samurai family. Ume was not considered good wife material by the locals because her aunt and uncle had not taught her how to run a proper Japanese household.

Running a household in Seattle did not prove to be a problem for the new bride. Shigekata and Ume had six children, including two sets of fraternal twins:

- Mitsuko, a daughter, born in 1923

- Shigesato and his twin sister, Masako (who died as an infant), born in 1924. (In keeping with the samurai tradition, Shigekata gave both of his sons names beginning with Shig.)

- Shigeyoshi and his twin sister, Shizuko, born on December 8, 1926

- Mutsuko, a daughter, born in 1928

Shigesato was a fixture at the Collins Playfield and was noted for his athletic ability. By contrast, “Little Shig” suffered from a range of ailments, including asthma, allergies, and skin problems, which often kept him off of the playfield and out of school.

Shig’s health problems meant that he spent more time with his mother than the other children and learned Japanese, which she spoke exclusively. He also grew up to the sounds of Western opera, which his father loved.

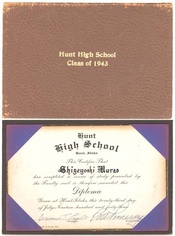

Shig’s high school diploma from Hunt High School in Hunt, Idaho, July 1943. He graduated while interned at the Minidoka Relocation Center.

Japan bombed Pearl Harbor the day before Shig’s fifteenth birthday. The family’s home and business were seized, and they were interned, first at the Puyallup Assembly Center south of Seattle, then at the Minidoka Relocation Center, north of Twin Falls, Idaho.

I was surprised to learn that the young Shig found Minidoka an adventure, almost a liberating experience. But Shig’s nephew, John, says many teens in the camps responded in a similar fashion.

Spared the chores that his father always had lined up for him at home, he began to read voraciously and spent a lot of time with Louis Untermeyer’s classic anthology, Modern American Poetry.

It was at this time that he discovered the poet who would become his favorite: Emily Dickinson. Shig knew many of Dickinson’s poems from memory and would recite them at opportune moments throughout his life.

The radio provided another enjoyable diversion at the camp, and Shig memorized many popular songs. Janet Richards writes of a shared car ride from Sacramento to San Francisco during which he sang one song after another in a “pleasing tenor voice.”

Shig would later refer to Pearl Harbor Day as “Yellow Power Day,” but while he was in the camp he delivered a speech to his fellow internees urging them to accept their lot. On April 27, 1944, Shig volunteered for the Military Intelligence Service and was released from the Minidoka camp.

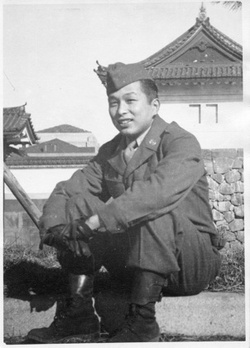

The army sent him to the Fort Snelling Military Intelligence School in Minnesota and subsequently assigned him to occupied Japan as an interpreter for the MIS. Shig liked to tell the story of sharing an elevator with General Douglas MacArthur when he was in Japan, but John says Shig would sometimes tell the story with a wink, so he was never sure whether it was true.

By the time Shig was released from the service, his family had regrouped in Chicago. He joined them there and enrolled in Roosevelt University.

Not long after he arrived in Chicago, Shigekata met a fellow issei who asked him if he needed a job. He took Shigekata to a restaurant and told him to tell the owner he knew how to work in restaurants. The owner gave him a knife and a side of beef, which Shigekata expertly butchered on the spot.

Shigekata ended up working for the Fred Harvey Restaurant in Chicago for ten years, until he and Ume realized their dream by moving back to Japan. Shigekata died of a stroke in 1963.

Shizuko went on to get an MA in child development and psychology at the University of Chicago and lives in Seattle at this writing.

Shigesato made his way from the camp to New York City with friends from the camp. To avoid harassment, they identified themselves as American Indians while traveling.

Shigesato would join the famed, all-Japanese 442nd Infantry in the European theater. After the war, he earned a degree at Springfield College in western Massachusetts and went on to become a teacher and principal in Chicago. He now lives in San Jose, California.

Mitsuko worked for the U.S Post Office for several years. Her husband died in the early seventies, and after Shigekata’s death in Japan, Ume moved back to Seattle and lived with Mitsuko until Ume died in 1984.

Mutsuko, the youngest of Shig’s siblings, found work as an editor for Harper & Row in New York City after the war and retired to Cincinnati, where she still lives at this writing.

Shig was more interested in reading and hanging out with literary and political types than in academic pursuits. Harold Washington, who would later become the first African-American mayor of Chicago, was a friend during this time.

Shig soon quit school and left Chicago without a word to anyone. A postcard from Miami let them know that he was okay, but the manner of his departure hurt and angered the family and set the stage for a simmering resentment that was only reinforced by his unorthodox lifestyle and subsequent arrest.

* This article is an excerpt from the online biography Shig Murao: The Enigmatic Soul of City Lights and the San Francisco Beat Scene.

© 2011 Richard Reynolds