Read Part 1 >>

The Silence of the Nisei

After the war, the newly freed Japanese busied themselves with building new lives, often far from the inhospitable West Coast of the U.S., where anti-Japanese sentiment lingered.

For as long as I can remember, my father, who died in 1997, never spoke of his experience of entering Manzanar at age 13 or the imprisonment that followed. This was not unusual among Nisei, who made up two-thirds of those in the prison camp. He and his family relocated to Chicago with the $25 they were each given upon being released. With such a meager amount to start with, the Issei and Nisei had little time for reflection. They worked ferociously, internalizing the shame and humiliation of their wartime experience.

Author Mary Matsuda Gruenewald repressed her emotions and tears related to her concentration camp experience until she was 74.

The writer Mary Matsuda Gruenewald has observed that for some Nisei it has taken decades before they were able to talk about their experiences openly; for others, the concentration camp experience is still a taboo subject. Gruenewald did not start processing hers until she was 74, when she was invited to participate in a writing class. In her 2005 memoir Looking Like the Enemy: My Story of Imprisonment in Japanese-American Internment Camps, Gruenewald wrote, “The dam broke loose when emotions and tears I had repressed for decades burst through, at times seemingly uncontrollable. At last, I was telling my story—a Nisei no longer willing to be silent.”

Although I never witnessed such a cathartic unleashing of emotion about the camps, my Issei maternal grandmother did talk about the humiliation of sleeping at Santa Anita race track in a barely converted horse stable that reeked of urine and manure; that was only the prelude to the even harsher setting of Heart Mountain, Wyoming. Defiance took a typically subtle and, to outsiders’ eyes, invisible form. In April 1945, as official services at Manzanar mourned the death of President Franklin Roosevelt, the man who had authorized what the government called “evacuation and internment,” my grandmother and other women in camp quietly prepared o-sekihan, the sweet rice and azuki bean dish that traditionally marks celebratory occasions.

Arcadia, California. Military police on watch-tower duty at the Santa Anita assembly center. From here my mother and her family were transferred to Heart Mountain concentration camp. (Source: Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority U.S. National Archives)

Most of the stories my relatives told about the mass evacuation, though—the largest forced migration in American history—were nostalgic tales of friendships made and pranks played. Hearing my grandmother’s account of “camp*,” I was incredulous that my grandmother credited the family’s three-year imprisonment at Heart Mountain with saving her husband’s health. (*The concentration camp experience was referred to by inmates simply as “camp*,” and the euphemisms “internment and evacuation” were so widely adopted by the Nisei that I did not realize how thoroughly they had infiltrated my vocabulary, despite being aware of what loaded and thoroughly debunked terms they had become. It was UCLA Asian American studies professor Lane Ryo Hirabayashi who printed out my excessive use of these terms in this essay, and reminded me of the scholarship on this topic done by Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga in “Words Can Lie or Clarify: Terminology of the World War II Incarcertation of Japanese Americans.”)

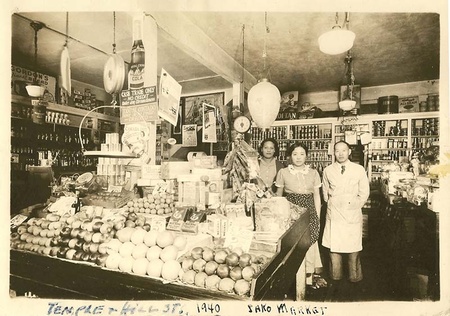

Before the war, my maternal grandparents operated a general store in downtown Los Angeles. As immigrants operating a small business during the Great Depression and then fighting increasing anti-Japanese sentiment during the buildup to the war, they worked ceaselessly. My grandfather put in 16-hour work days seven days a week, helped out by my grandmother and their teen-aged son, while my great-grandmother tended to my mother, still a baby. “I think his health would have broken down if he had kept up that pace,” my grandmother said of her husband. For many first-generation immigrants, living a sequestered life among their own people, even under coercion and behind barbed wire was easier than fighting to eke out a living in a racist environment.

My grandparents, Tomiko and Gennosuke Matsumoto at their market at Temple and Hill Streets in Los Angeles, 1940. When the orders to evacuate came, they were forced to sell the store and its contents for $600, a fraction of its value.

Although I didn’t know much about the concentration camps, I knew enough to be somewhat shocked and appalled at her attitude. It seemed too obedient, too accepting, a way of rationalizing a shattering injustice. It helped a little to learn that my grandparents were not the only ones who felt this way: The poet and editor Lawson Fusao Inada wrote of the prison camps in Only What We Could Carry: The Japanese American Internment Experience, “For some Issei, who spent years of zealous struggle to build a life in a new country, there came an ironic escape from the drudgery of their former lives.”

© 2011 Nancy Matsumoto