Chogi Higa basked in his backyard in Gardena, California. It was in full bloom with white orchids and the orange and cherry blossom trees he had brought from his birthplace: Okinawa, Japan. It is a weekly ritual for Higa, a 69-year-old radio DJ, to meditate on what he is going to talk about on his radio program, Haisai Okinawa. His weekly program focuses on news germane to the Japanese and Okinawan communities in Los Angeles.

“I get excited whenever I think about what I am going to talk about on the program this week,” said Higa.

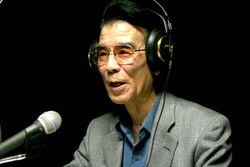

Once a week, Higa goes to a recording studio at Team J Station in Lomita, a city just next to Torrance. It is America’s only 24-hour radio station that broadcasts in Japanese. Before recording, he carefully goes over the text he has written on a yellow piece of paper with the important words highlighted in red pen. He checks his audio. “Check, check, check, one, two, three,” Higa says into the microphone. And then he’s ready to go.

“Cha-Ganju-,Yami She-Mi-.” Koichi Yamakawa, the co-host of the program, greets Higa in Uchinaguchi, Okinawa’s distinctive language, which is different from Japanese — the phrase means “How are you?” in English. Higa, in return, answers, “Cha-Ganji-, So-i Bi-n,” meaning “I am fine.”

The 30-minute program is aired on Saturday and rebroadcast on Sunday. In the first section of the program Higa reports on Japanese and Okinawan community news. In the second part, he gives a lecture about the ancient mythologies and history of the Ryukyu Kingdom, or Okinawa before it was annexed to Japan in 1879. Higa, a taciturn man, whose eyes are always serious under his brown glasses, gets animated and eloquent whenever he talks about Okinawa. Sometimes he gets so excited that he runs out of time to cover his complete script. Higa said he wants to share as much of his knowledge with his listeners as he can. “I want people to feel Okinawa by listening to my radio program, especially the younger generation,” said Higa.

The program started six years ago, when Yamakawa, the president of Team J Station, was planning to start a radio program designed to remind Japanese Americans of where they come from. When Yamaguchi met Higa, his gut feeling told him Higa was the one.

“Mr. Higa is an unusual man with great love for Okinawa and a vast knowledge of history. He is also one of the few people here who can speak Uchinaguchi. I even feel as though I were an Okinawan, learning so much from him,” said Yamaguchi, who is originally from Fukuoka, a prefecture of southern Japan.

As newspaper companies across the country are being forced to close, Japanese newspapers in the United States are barely surviving. Nichibei Times, a San Francisco-based Japanese newspaper, ended its 63-year history in August 2009, because of its financial struggles. Two months later, Hokubei Mainichi, another Japanese newspaper, followed suit.

However, Okinawan, or Uchinanchu journalism, spearheaded by native Uchinanchu like Higa, and others of Okinawan heritage, is thriving in Los Angeles and helping to pass Okinawan tradition and culture on to the younger generation.

Higa was born in 1940 in Nakagusuku, a village located in the middle of mainland Okinawa. It faces Nakagusuku Bay, which is a natural habitat for coral reefs. Back then, Okinawa was poor, and had become even more so by the time the Battle of Okinawa started in 1945. It was the biggest battle that took place on Japanese soil between Japan and the Allied forces. That clash took the lives of more than 90,000 Okinawan civilians. Higa grew up amid the despair of post-war Okinawa, while the island was under U.S. military administration from 1945 to 1972. “I was fascinated by affluence of America, and I longed for America,” Higa said.

In 1960, Higa moved to Burbank, California, to start college at Woodbury University, majoring in foreign trade. There, he was shocked by Japanese students who knew nothing about Okinawa. “American students, and even Japanese students, asked me where Okinawa is, and if it was part of Japan and, and if I ate American food or Japanese food,” said Higa.

Initially, his goal was to go back to Okinawa after college to teach social studies and history. But Higa, now the president of the Okinawa Association of America, said his experience made him determined to instead be a cultural ambassador, helping link Uchinanchu in Okinawa and Uchinanchu in America. He wanted to introduce Okinawa’s culture and traditions to Americans and Japanese. To accomplish his mission, he decided to stay in Los Angeles to earn money. He took a job with a trading company.

One of the concerns Higa has is the disappearance of Uchinaguchi, the Okinawan language. “The younger generations are Uchinanchu by birth because Okinawa-ness is in their blood, but language is essential to understanding of our culture,” said Higa, who grew up speaking Uchinaguchi and is one of the few people in Southern California who are fluent in it. Higa said younger Uchinanchu often learn Okinawan dance, but their understanding of the dance is superficial. Because all Okinawan songs are sung in Uchinaguchi, dancers cannot express the deeper emotion of the songs they are dancing along to unless they understand the language.

Uchinaguchi was once banned as a “barbaric language” by the Japanese government, which annexed Okinawa in 1879 after a military incursion. The Japanese government forced assimilation policies on the Uchinanchu, and mandated that residents speak Japanese in public places. In school, those who spoke Uchinaguchi had to hang placards from their necks that said “Dialect,” a punishment reminiscent of the “dunce caps” schoolchildren in the west were made to wear.

After the war, the U.S. military administration in Okinawa encouraged the revival of Okinawan culture as a means of winning support from the Uchinanchu. After Okinawa was returned to Japan in 1972, the Uchinanchu were never forced to speak Japanese again. Yet, in February 2009, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, or UNESCO, designated the language Yaeyamago, a dialect of Uchinaguchi, as one of the most endangered languages in the world.

In America, Uchinaguchi faces a much more dire situation because it is only spoken by first generation immigrants, and they are dying out. Their children and grandchildren are fully assimilated into American society and never had to learn the language.

Higa, who thinks language plays a critical role in preserving culture and understanding what it is means to be Uchinanchu, started a Uchinaguchi class in 2002 at the Okinawan Association of America. The class started with only 7 people but now he has more than 40 students.

Higa’s class helped James Gushiken Horine to learn about his heritage. Horine is the son of an American father and an Okinawan-American mother who came to the United States when she was 14. “I definitely felt different from other Americans. At the same time, I didn’t understand what my mother and grandmother were talking about in Uchinaguchi. They didn’t talk about Okinawa with me, either,” said the 24-year old Illinois native.

Horine said he was always curious about his identity, and that when he went to Okinawa, he felt the biggest barrier to really understanding the culture was the language. “Without knowing the language, I didn’t feel I was part of their culture,” said Horine. He is struggling to learn Uchinaguchi but said he is eager to help preserve Uchinaguchi so that he can protect his heritage.

Higa started his language class at about the same time he launched his radio show. “I thought the radio program was a great tool to reach out to more people. So I incorporate Uchinaguchi lessons,” said Higa.

* This article was originally published on Okinawa: Past, Present and Future.

© 2010 Ayako Mie