When asked about their memories of Terminal Island, many Japanese Americans who spent their childhood there think “furusato,” home sweet home. In the early 1900s, many Japanese immigrants from Wakayama Prefecture settled there, making a living as fishermen. The community thrived and grew into a place where families knew one another, a place with little or no crime, a place of no worries. Having cherished childhood memories may not seem unusual, but given the devastating history of this area, now known as San Pedro, the fond memories held by Japanese Americans who grew up on Terminal Island is nothing short of remarkable.

In 1941, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, a number of Japanese American men residing on Terminal Island were arrested, without warning, by FBI agents. Families were not told where the men were being taken or when they would return. On February 25th, 1942, all residents of Terminal Island were ordered to evacuate within 48 hours and were later incarcerated in camps. Because many Issei had already been arrested, young Nisei were often put in charge of their family’s evacuation. Eventually, the entire village of Fish Harbor at Terminal Island had been razed. No one was allowed to return there to live.

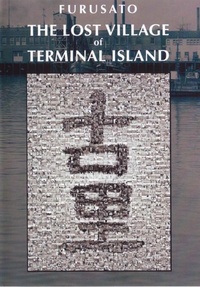

Now there is a film to document this chapter in Terminal Island’s history. David Metzler, the director of Furusato: The Lost Village of Terminal Island, was interviewed by the Japanese American National Museum and commented on the film and his experiences in making it.

David Metzler’s interest in the history of Terminal Island began when he was part of a UCLA program called Discover LA. Through the program, he visited the Great Wall of Los Angeles mural in the San Fernando Valley which depicts the history of California. According to Metzler, “Besides being impressive in size and scope, the mural told California’s history from a unique perspective—the perspective of people who were displaced—Native Americans; the community of Chavez Ravine prior to Dodger Stadium; the internment. That mural really inspired my interest in Los Angeles history and eventually it led me to Rick Perkins, who had done a dissertation on the Japanese community on Terminal Island. When I found out the original residents still met regularly, I wanted to find out what inspired this lifelong bond.”

With the assistance of Allyson Nakamoto, who found a number of the writings from the Terminal Islanders in the resource center at the Japanese American National Museum, Metzler was able to connect with many of the Japanese Americans of Terminal Island through regular picnics, a New Year’s party, and even golf outings organized by the group. However, although the initial contact was fairly easy, David Metzler still faced a number of obstacles. “We had some challenges convincing people to sit down and speak with us—many thought their life was not ‘interesting’ enough to be filmed, but by enlisting the help of many friends and family (to help convince them), we were able to conduct many hours of oral histories. Our first interview was with Tommy Okimoto, who was one of the last people to see the homes on Terminal Island. He was helping many families move off the island after they were given 48 hours notice to vacate, so he drove what was probably the last truck off the island. A few weeks after our interview, he passed away. We realized time was not on our side and that we were very lucky his daughter and wife were able to convince him to do the oral history; otherwise, that piece of history could have been lost forever.”

As one would expect, the experience of making the film strengthened the director’s connection to the Japanese American community; it also deepened his appreciation and admiration for the Nisei who persevered through World War II. Metzler commented, “I find it incredible that the same generation which suffered such a great injustice and loss of civil liberties came back to rebuild their lives and community, raise a new generation, and take care of their parents. I’m very proud to have known the Terminal Islanders, and I’m honored that they have invited me to their events and into their homes. I hope that shows through in The Lost Village of Terminal Island and that people from any ethnic background can appreciate and admire this community.”

Not surprisingly, the film has had a significant impact on its viewers. When the film was featured in the L.A. Harbor International Film Festival in April of 2007, the film was, to say the least, enlightening. Despite the magnitude of the evacuation of Terminal Island, some residents of the area were not aware of the island’s history; others even had to be convinced that the events actually took place. Some simply found answers to long-held questions answered in the film. Although difficult to describe, Metzler found the experience of screening the film at the L.A. Harbor International Film Festival to be “at once entertaining and poignant.”

After the screening, hundreds of San Pedro residents remained for a question and answer period moderated by the film’s narrator, Rob Fukuzaki. Metzler recalled, “I heard one woman had a tear in her eye because the last time she had seen the Japanese was in school when she was a young girl—and she never really knew or understood what happened to her friends. Now, 65 years later, she was sitting in the same room with many of them, in the same Warner Grand Theatre that they used to attend...and now she knew.”

The last fishing cannery on Terminal Island closed in 2001, but the spirit of the Japanese Americans who were instrumental in the fishing industry that began there remains. On July 6th of 2002, a memorial was dedicated to the many Japanese Americans who still refer to Terminal Island as “furusato,” their home sweet home. Through The Lost Village of Terminal Island, David Metzler has also established a lasting memorial to the strength and undying optimism of these Japanese Americans, ensuring that their incredible personal stories and life histories will not be forgotten.

* This article was originally published on the Japanese American National Museum Store Online.

© 2007 Japanese American National Museum