Read Part 1 >>

It was in USC Law School that some friendships developed which were to change the course of many lives. Marion Wright became acquainted with two Japanese students, both aliens, who were studying law in the United States. One of these, Motohiko Miyasaki, returned to Japan soon after graduation. The other man, Sei Fujii, became a close friend. Fuji later became the founder and editor of the Japanese newspaper, Kashu Mainichi, and an ally on the long road toward civil rights for Japanese people in the United States.

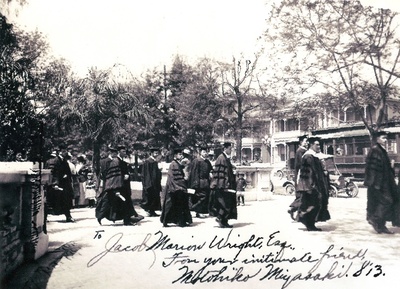

USC Law School graduates processing after commencement through Pershing Square in 1913. Wright is third from the right and his friend, Motohito Miyasaki, is fifth from the right.

It was rather unusual to find Japanese nationals studying for the professions, as most of those who came to America at that time were farmers. These newcomers made it a practice to lease land, to improve it, and then to work diligently to raise fine vegetables, fruit, and flowers. Justice Jesse W. Carter of the Supreme Court of California wrote:

The Japanese farmers possessed a remarkable knowledge of soils and how to treat soils for the production of certain crops; an expert knowledge of fertilizer and of fertilizing methods; a great skill in land reclamation, irrigation and drainage; and a willingness to put in the enormous amount of labor required in intensive farming operations. They reclaimed vast areas of the west including cut over timber lands and delta lands of the northwest. The most striking feature of Japanese farming in California has been the development of successful orchards, vineyards, or gardens on land that was either completely out of use or was employed for far less profitable enterprises.1

Many people who were uninformed about farming observed the fine gardens and orchards that the Japanese succeeded in reclaiming and concluded that all the best land in California was being taken by foreigners. Prejudice began to grow. It was not only people interested in agriculture who resented the Japanese. Prejudice was a continuation of the ill feeling toward all Asians which began to flourish in the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s. In the 1850s many men from China came to work in the mines, while in the 1860s and 1870s thousands of Chinese men were brought to California to work as laborers building the railroads. The general population was suspicious of the unfamiliar appearance and customs of the immigrants. Hate and fear began to rise and through the years many violent and fatal incidents involving Chinese took place.

The California legislature passed discriminatory laws, some of which were declared unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court. Anti-Chinese fervor was so great that in 1882 the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed by the Congress of the United States and signed by President Chester A. Arthur. From this time on Chinese nationals could not enter this country. The law was renewed in 1892, and in 1902 was extended indefinitely. As the Chinese population dwindled, the Japanese who came to California during and after this period, inherited the prejudice which had previously been directed toward the Chinese. Numerous bills were introduced into the legislature limiting the rights of Japanese. In the 1913 session of the State Senate and Assembly, thirteen such bills were considered. Speeches in the Capitol were filled with hatred for the Japanese. The San Francisco School Board voted segregation for children of Japanese ancestry in the year 1906.2 In Los Angeles, anti-Japanese sentiments was less blatant. “The racial attitude was tolerant as long as the tolerated, mainly those of Mexican descent, but also American blacks and those of Japanese descent, were willing to work in the fields and orchards and then disappear.”3 The Japanese with their energy and talents were not willing to disappear. Many cases were tried in both the lower and appellate courts, and even in the United States Supreme Court in an effort to establish their right to lease certain lands, to remain in the United States, to have the right of guardianship over their minor children who were citizens, and above all to own land. In most of these cases the decisions were against the Japanese, so great was the prejudice against them.4

Because of the prevailing sentiment, few befriended these Asian aliens. Marion Wright’s early poverty and Christian values, as well as his legal training, prompted him to appreciate and to help those against whom the majority of the citizenry directed derision and denial of rights. The contrast in appearance between friends was great. The small, polite Japanese gentlemen and the tall, raw-boned westerner found common ground in the respect and trust which they had for each other. Wright had the gift of gentle, well-directed humor, which evoked a relaxed response when serious or tense situations arose.

In 1920 he won a case for Japanese clients before the California Supreme Court involving the quality of spinach which was delivered to a cannery.5 The amount in question was $2,283.66 for 10,965 pounds of spinach. Later in the District Court of Appeals he defended Japanese farmers accused of spraying mustard greens in a harmful way.6 In both cases the appeals were decided in favor of Wright’s clients. The fact that these rather small cases involving modest amount of money went to a higher court, demonstrated that Wright had tenacity and a deep commitment to justice. He did not give up with an adverse judgment against his clients.

Although Marion’s basic personality was characterized by kindly wit and humor, his courtroom manner was dignified and forceful. His arguments to juries were memorable for their passion as well as for their logical reasoning, and he was relentless in obtaining the truth from a witness whom he felt was hiding the facts. His future son-in-law, George La Moree, who heard him for the first time in court, was astonished at the fervor and intensity with which his amiable father-in-law-to-be uncovered hidden truths.

J. Marion had a fine reputation among members of the Los Angeles County Bar and on a number of occasions was selected by the Presiding Judge of the Superior Court to sit as Judge Pro Tem on cases where lawyers for both sides agreed to this arrangement. He had the unique ability to analyze legal issues and to express legal conclusions in a powerful manner which really sounded like “the law.”7

Notes:

1. Sei Fujii v. State of California 38 Cal 2d 718,242 P 2d 617 (concuring opinion of Carter, J., p. 738 1952).

2. Frank F. Chuman, The Bamboo People (Del Mar: Publishers Inc., 1976), pp. 23–24.

3. Kenneth D. Rose, “Dry Los Angeles and Its Liquor Problems in 1924,” Southern California Quarterly, LXIX (Spring 1987): 51.

4. Porterfield vs. Webb 263 US 225 Nov. 12, 1023; Frick vs. Webb 263 US 326 Nov. 19, 1923.

5. Ramsaur v. Cal. Veg. Packing Co, Superior Court of Los Angeles County #LA21449 1920. Trial Transcropt in possession of author.

6. Binion v. Sasaki 5 Cal App 2d 15 41 P2d 585 1935.

7. Owen E. Kupfer, Oral history 1988, San Gabriel, California.

* “J. Marion Wright: Los Angeles’ Patient Crusader, 1890–1970” by Janice Marion Wright La Moree was first published in Volume 62, no. 1 (Spring 1990) of the Southern California Quarterly, then reprinted separately in a limited edition that same year.

**All photographs are courtesy of the author

© 1990 Janice Marion Wright La Moree