They were early pioneers. And especially on farms it was very difficult for them."

--Kara Kondo

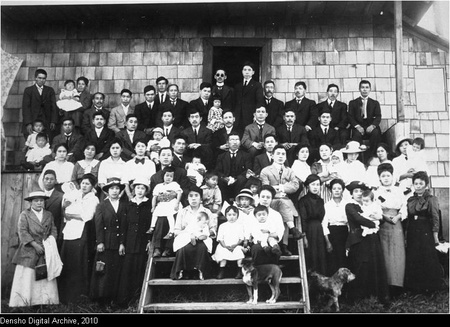

The stories Nisei interviewees tell about their parents form a pattern: Fathers left the villages and rice farms of Japan at the turn of the last century to earn money in Hawaii and mainland United States. Some still in their teens, they took grueling jobs at farms, lumber mills, railroad camps, and fishing canneries; others worked as houseboys. Once they earned enough money, the men returned to Japan to find a bride or sent for a picture bride. Babies arrived, and the Issei built churches and Japanese language schools to educate the next generation.

They formed business associations to support each other in an inhospitable country. They turned undesirable land into flourishing farms by working dawn to dusk, and even into the night. While many decided to make America their permanent home, others expected to return to Japan. As Ike Ikeda says, "I had a feeling that, like many immigrants, they were ready to make their mint. They thought they would really get rich in a hurry and go back. But that never happened." What happened to the Issei instead in the 1940s no one could have anticipated.

Because Densho began collecting oral histories after most of the Issei generation had passed on, the stories we have of them come secondhand through Nisei memories. Fortunately, the family stories shared by many Nisei are vivid--fond and respectful as well. Interviewees speak of how hard their parents worked, and how they instilled in their children the values of integrity, tradition, and family honor.

Kara Kondo describes life in Yakima Valley in Washington:

A lot of the Issei lives were the same in that we were a self-contained community. We were able to maintain our Japanese foods and customs, and on New Year's Day they had mochitsuki and the same kind of customs that they were used to. But it was a very difficult life, and I have a lot of memories about living out in the country and having wild horses come into our land and having to chase them out and having the sheep coming in to graze on the last bits of alfalfa in the fall. These are memories that you have. And very often we could hear the coyotes at night and often see them around the haystack...

Of course, and we realized that life was hard for all the Issei, or anybody, regardless of whether they were Caucasian, because they were pioneers in the Yakima valley. They were early pioneers. And especially on farms it was very difficult for them.

Among the obstacles and discrimination the Issei faced, alien land laws prevented Asian immigrants from owning land. Kara's parents and thousands of other Issei farmers had to combine diligence and resourcefulness to turn a profit. In her case, the family leased reservation land from the Yakama Indian Nation. Along with other Issei pioneer famers, they cleared the land and planted new types of crops in the valley.

It was very difficult just to clear a land out of sagebrush with just horses and manpower. That's one of the reasons why they had small parcels of land, which led them to farming, crops that would produce more income from small acreages. That's when they introduced such products as the row crops of tomatoes and corn, and peppers and cantaloupes and the melons. They introduced these small crops that grew very well in the climate and the soil conditions on the reservation…At that time they did not go into orchards or trees because that required some permanence, and the Japanese farmers depended on leases. They would move from one parcel of land to another depending on, I imagine, the lease agreements and the kind of soil that they were seeking. So, in many ways, they pioneered different crops for the lower valley.

While farming supported a majority of Japanese Americans, many Issei owned small businesses that served the Japantowns of the West Coast. Densho interviewees describe living upstairs from a small grocery store, barbershop, photo studio, or five-and-dime store. Katsumi Okamoto says his family ate well because they ran a grocery store (also leased), and he remembers delivering groceries to a dentist in return for dental care. His father did well even during the Depression but lost the business when World War II started: "He seemed to have done very well, but his problem was he let people charge, and I wonder, I heard that he never collected on a lot of the bills. And once the war started, that was it. He lost a lot of money, but he was a very gentle-hearted person that helped people out."

The years devoted to building up successful farms and businesses went up in smoke after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Within hours of the attack, FBI agents swooped down on Japanese American communities and arrested thousands of Issei men whose names had been compiled years earlier as potentially "dangerous" aliens. Fathers who happened to be business leaders, Buddhist priests, Japanese language teachers, or influential in some other way were separated from their wives and children. Suddenly they were treated like criminals. Many were held for years in Department of Justice internment camps while their families were confined in War Relocation Authority camps. Once-proud Issei men eventually rejoined their families, but robbed of their authority and self-respect.

More fortunate Issei men arrested after Pearl Harbor escaped the separate confinement. Sisters Ayako and Masako Murakami, who ran the Higo Variety Store in Seattle, explain that their father always said, "America is my father, and Japan is my mother. They had to be on good terms." When he was taken to the immigration station for questioning, their father answered cleverly:

He was stuck at immigration for a while, but they released him. They questioned him, and Papa was telling us the kind of questions they asked. They came right out and said, "Who do you want to win the war, Japan or America?" And most of the Japanese gentlemen said America, but my dad says, "Neither." I said, oh you said that? He said, "Neither." He says couples fight like husband and wife, and says, "I don't want either one to win, or lose." And so they released him. I said, "Papa, you're really smart." I never thought of it that way, you know.

Some Nisei interviewees report that their parents believed Japan would win the war, and even at the very end believed that Japan would never surrender. Yet they encouraged their Nisei children to be loyal to their country of birth and citizenship. Other Issei had become more attached to America as the years went by, even though they were not permitted to become U.S. citizens. Paul Bannai recalls, "I remember when the war started, they emphasized the fact that they had been here for many years. I was born and raised here. I should think in terms of being a good American and serving this country, because there's no other country that I owe any allegiance to. "

In addition to depriving the Issei of their farms and businesses, the forced removal and incarceration permanently damaged their status as heads of households and communities. Camp administrators favored the English-speaking Nisei, placed them in positions of authority, and forbade the Issei from voting or holding office in what passed for self-government in the camps. Overnight, generational roles changed.

May Sasaki remembers the idle old men at Minidoka, Idaho, incarceration camp:

They were the heads of families, and then they found themselves not the heads of families anymore. I think that was very difficult for them to accept. So there were times when there was tension and they were fighting--all the things that occur when the leadership is being challenged in one's family. That's too bad because the self-confidence, the feeling of pride in being the head of a family, when that is taken away from you, we found some Isseis that weren't ever able to get back that same feeling of what it is to be the head of one's family. I felt sorry about that. You'd see some of the older gentlemen kind of sitting there. They would pick up and do things like play go or hana or whittle or make things...

I know people like to joke and say, "Well, I had more free time on my hands so I like that," and everything. But I really think if they were to be given a choice as to whether to go to camp and get that forced retirement or stay out of camp and have their freedom and have their leadership and their sense of pride and self-confidence, I'm sure they would never have said that. But I think it's a matter of... what is it? It's a denial which then lets you survive a situation and just laugh it off and say, hmmm. It's like when you get hit doing something foolish, you say, "Oh, it didn't hurt me anyway." Well, it did hurt, and you could see it in some of the ways they were not able to ever regain a sense of who they were. And that was kind of a sad situation.

The Issei women also lost their hopes for prosperity and self-determination. Sue Embrey, incarcerated at Manzanar, California, recalls her widowed mother's time at the camp. After a lifetime of endless work, some Issei could enjoy the enforced leisure, but Sue's mother had her sorrows too:

I think she got arthritis, because her whole left side, she was unable to move her arms, and we ordered dresses from the catalogs, Montgomery Ward and Sears, that had buttons all the way down the front so we could get her dressed. But she used to walk a lot around camp, and she took part in what they called utae, which is a capella singing, telling a story. She loved to sing, so she got involved with that. And later on she went to Red Cross classes where they rolled bandages for the army. I think for her it was probably a good time, but she never talked about the fact that we lost our grocery store that she had bought after my father died. She always said it was better to be in business for yourself. And so here she was, left a widow with eight kids, and so she cashed in her insurance policy, and bought this little grocery store outside of Little Tokyo, and she really enjoyed being a businesswoman. Then when we lost that, it was a little over a year, year and a half maybe, after she bought it that she lost it, she never mentioned it. But I think it really kind of killed her dream of becoming an independent woman. And we sold it to a young Mexican American couple, and they took care of it for a while. But she never really was able to get back into doing anything like that. I think that she probably was very disappointed about that, but she never, like I said, never mentioned it.

A frequent refrain of the Nisei is to lament that the Issei generation had been the most harmed by the incarceration, and yet so few lived to see redress arrive. So many had died before they could receive the much-deserved presidential apology for their wrongful imprisonment. After money was appropriated to fulfill the promised $20,000 to each survivor of the incarceration camps, the checks went to the oldest first. Photos from 1990 of checks being handed to Issei elders drive home how much time had passed since the camps closed before the injustice was acknowledged.

The Nisei take consolation in knowing that their parents' Japanese culture helped them cope with the indignities of racism and the losses of incarceration. It may be hard for younger generations raised in the post-Civil Rights era to understand, but the common memory is of Issei parents saying shikata ga nai, "it can't be helped, it must be endured"--a passive expression, but spoken by a generation that was anything but weak.

* This article was originally published on Denshō: The Japanese American Legacy Project.

© 2010 Densho