On March 30, 1942, 257 Nikkei residents of Bainbridge Island, Washington, walked onto a cross-sound ferry to Seattle under military guard and boarded a train bound for the Manzanar Reception Center in California’s Owens Valley, 200 miles east of Los Angeles. This transport began the forced exile of 92,000 Japanese Americans directly from their homes in Washington, Oregon, California, and Arizona into so-called “assembly centers.” There they remained for approximately 100 days until their transfer to permanent “relocation centers” located in remote regions of the country.

Over the past forty years many books have been published on the relocation centers, and in the past decade significant light shed on the internment camps for Japanese nationals held as enemy aliens. To date, however, little has been written about the assembly center experience, and the first scholarly book on the subject will not be published until next year, sixty-seven years after the fact. Why is this?

First, the assembly center period lasted just seven months, brief compared to the overall incarceration experience. Second, until recently army archives have been more difficult to access than War Relocation Authority records. And third, for many assembly center survivors the trauma of their abrupt transition from freedom to captivity has blurred memories and, in some cases erased them, altogether.

Some here today may therefore know less about the assembly center experience than other aspects of the incarceration. Here, then, I would like to provide some highlights of this transitional period.

* * *

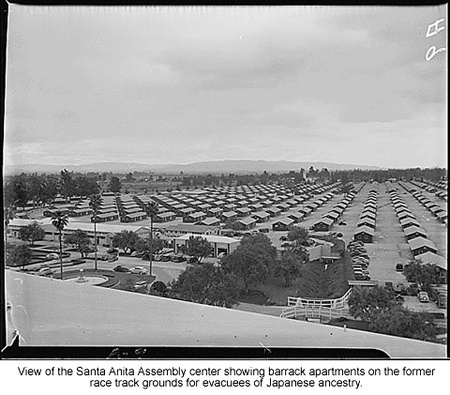

The US Army’s task of first evicting then sheltering 100,000 men, women, and children was daunting. In early March 1942 planners appropriated fifteen existing public facilities located near city limits with significant Nikkei populations, and built a sixteenth, Manzanar, from scratch. The assembly center sites included thirteen in California, and one each in Arizona, Oregon, and Washington.

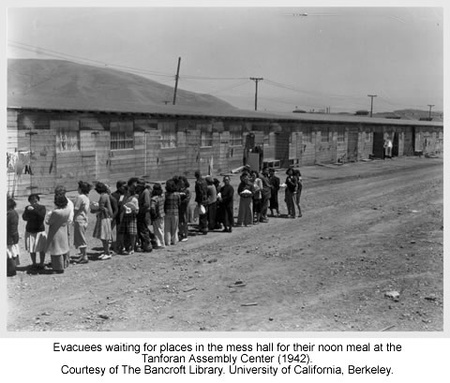

Fairgrounds, racetracks, and livestock pavilions provided acreage and infrastructure necessary to assemble the centers quickly. Built for temporary occupancy the centers offered few amenities and meager social services. Inmates ate in mess halls and slept in noisy barracks while enjoying little privacy. At several centers, notably the Santa Anita and Tanforan racetracks, many unlucky families occupied whitewashed animal stalls that reeked of manure. Poet James Mitsui provides a poignant detail from his family’s Tanforan experience:

Hay, horse hair & manure

are whitewashed to the boards.

In the corner

a white spider is suspended

in the shadow of a white spider web.

* * *

As the Army’s forced evacuation approached, Nikkei communities prepared for exile. Advertisements appeared in local newspapers, and readers soon learned there were bargains to be had:

- JAPANESE evacuation necessitates immediate sale 55-room brick hotel. Best linens, furnishings: steam heat, steady tenants.

- 1936 DESOTO sedan. Attached overdrive, gas-saver transmission; four new tires. Evacuation forces sale.

Problems for farm operators often proved complex. Long-term leases had to be transferred, expensive farm machinery disposed of or stored by sympathetic neighbors. Until the last minute the government pressured growers to plant for the 1942 season, equating continued production to a measure of national loyalty; soon crop neglect or damage elevated to an act of sabotage.

The eviction operation went smoothly in part because of civil control stations the Army set up in community halls, school gymnasiums, and other public places throughout Nikkei centers of population. There government personnel registered families, provided pre-induction medical examinations, and helped arrange for storage or sale of properties. Assigned five-digit identification numbers relegated family units to anonymity: the Itois of Seattle—family 10710; the Unos—10936.

On each appointed evacuation day families arrived at pre-arranged gathering points dragging their personal belongings. The gathering area at Eighth Avenue and Lane Street near the heart of Seattle’s Japantown was located in the city’s red-light district. Shosuke Sasaki remembered baggage lining both sides of the street and Nikkei standing in a chilling spring drizzle awaiting the order to board buses. Among them were his sister and her two infant children. The door of a brothel opened, and the madam invited the three into her parlor to wait out the rain, an act of kindness recalled with emotion a half century later.

New assembly center arrivals faced strangers in unaccustomed close quarters, sharing communal realities of mess halls, latrines, shower rooms, and the barracks, themselves. Late at night was no exception, for open spaces between apartments amplified sounds that ricocheted through the entire darkened barrack. Insomniacs endured snoring, coughing, whispering, arguing, crying, pacing, and sounds of lovemaking. As rain fell on the tarpaper roofs at Puyallup Assembly Center, water trickled down low angled slopes through cracks and onto blankets, clothes, and faces. Such misery informed the early experience of Nikkei from Washington to Arizona as they endured the shock of their sudden loss of freedom.

Nevertheless, inmates built a semblance of community. Many went to work, most to the mess halls, with others employing specialized skills as clerks, organizers, and medical aides. Nisei teachers and volunteers guided young charges through “vacation school.” The payroll ranged from $8 per month for unskilled labor to $16 for professional workers. In 2008 dollars, over-worked physicians earned a meager $212 per month.

Other workers organized recreational activities to help stave off boredom and boost morale: boxing, kendo, sumo, basketball, horseshoe pitching. Softball leagues provoked instant intra-camp rivalries. Women formed knitting, sewing, and crochet groups, while older men set up go and shogi tournaments. Dance-crazy young people headed for the recreation halls to swing to the recorded sounds of Glenn Miller.

Yet for most people, absent distractions provided by employment and volunteerism time passed slowly. Tamako Inouye remembered the summer boredom she and friends experienced at the Puyallup Assembly Center:

There was this space between the barracks. When it was really hot everybody would go to one side of this lane, lean against the building, and just sit there. And later on in the day when the sun changed its course we’d go to the other side.

* * *

Although physically isolated from their former communities inmates accessed news and world events through AM radio and mail subscriptions to English language newspapers, including the Pacific Citizen. In addition, each assembly center published a mimeographed newsletter with Nikkei editorial and production staffs. Some had evocative names: Walerga Wasp; Pinedale Logger; Tanforan Totalizer; Fresno Grapevine; all issues were distributed free. Through them center managers communicated regulations and directives, while editors reported center-wide happenings, such as births and deaths, ball scores, and Sunday church schedules. Content was censored, leaving the editor of the Manzanar Free Press to note privately, the only thing free about his publication was the subscription fee.

With no access to telephone or freedom to move about, letter writing provided the sole means of communication with the outside world. Although the newsletters were censored, first-class mail passed freely.

* * *

Early incompetence by Army planners led to occupancy of assembly centers before installation of refrigeration and other safe food storage equipment. For a brief time inmates ate army rations designed for troops in the field. While food on mess hall tables soon became more palatable, healthful sanitary conditions evolved more slowly, resulting in public health threats everywhere.

Outbreaks of diarrhea plagued most assembly centers because of inexperienced workers and improper oversight. In early May, spoiled Vienna sausages caused a severe flare up among inmates at Puyallup. Symptoms emerged after curfew and the commotion led to near panic by sentries in the guard towers. Flashlights helping light the way, with all public stalls occupied pinpoints of light moved erratically in the darkness. Fearing an insurrection, sentries manned the spotlights and called for reinforcements. But with order soon restored tragedy was averted, and the epidemic passed quickly. Given the crowded and unsanitary conditions at most assembly centers, it is surprising more frequent, if not serious, outbreaks of gastroenteritis did not take place.

Most health care was provided by Nikkei doctors, nurses, dentists, and pharmacists, themselves inmates. The centers’ temporary status relegated medical facilities to infirmaries or emergency hospitals. Even so, Army statisticians recorded a total of 5,981 births, 271 operating room surgeries and, in the month of August alone, 30,000 outpatient visits.

* * *

With the nation’s farm labor crisis deepening as many draft-age workers entered military service or took on higher paying jobs in the war industry, while sugar processors turned to the assembly centers as an untapped labor source. Recruitment at the Portland and Puyallup Assembly Centers began in mid-May, and by the time the assembly center period ended nearly 1,600 strong-backed volunteers from half a dozen centers worked the sugar beet fields of the American west. By November Nikkei farm hands harvested 25 percent of Idaho’s sugar beet crop, with the state’s farmers expressing gratitude.

Nisei college students, their educations on West Coast campuses abruptly suspended, had slimmer opportunities to leave the assembly centers. While the next three years would see over 4,000 students entering inland colleges and universities, the student relocation program began modestly in the assembly centers with 360 transfers. The Army opposed student relocation on national security grounds and imposed sufficient restrictions permitting only a few colleges and universities to participate. Students had to document their financial resources and undergo cumbersome FBI intelligence checks. As a result, most Nisei prepared their college applications while in the relocation centers.

* * *

Transfer to the relocation centers began in June and continued through October. Wartime demands to move troops on the nation’s rail lines forced the Army to use re-commissioned passenger cars, hulks that generated universal complaints from Nikkei passengers and officials and added to the humiliation of incarceration. Dirty, with inadequate water pressure, faltering air conditioning, and sealed windows preventing air circulation, only the passing landscape provided temporary diversion from the misery.

On November 1, 1942, six days after the final transfer of inmates from Santa Anita Assembly Center to the Manzanar Relocation Center, the Army under prior agreement with the War Relocation Authority turned over jurisdiction of 111,000 Japanese Americans. The assembly center period then came to a close.

* * *

One silver lining to the difficult assembly center period may be that life in these holding pens prepared inmates for the several years of incarceration that lay ahead. I will leave you with Sharon Tanagi’s insight from her own experience:

I think that was the best adjustment really the Army could give us, to herd us all together to get us used to queuing up in lines and being a bit more patient and learning to get along because we were in such tight quarters. I think without them knowing, it was the greatest thing to do. When we went to Minidoka the trauma wasn’t there.

* Louis Fiset was one of the panelists in a presentation titled "An Overview of Nikkei Incarceration: World War II Assembly, Relocation, Isolation, Segregation, and Internment Camps" at the Enduring Communities National Conference on July 3-6. 2008 in Denver, CO. Enduring Communities is a project of the Japanese American National Museum.

© 2008 Louis Fiset