Naotaro Ito was born in 1886 as a second son to a rice farming family in Kitsuneji, a tiny rural hamlet in Aiichi Prefecture, near Nagoya, Japan. He received a basic elementary education then was sent to a bicycle shop merchant to serve as an apprentice in his early teens since only the eldest son was slated to inherit the farm, according to long standing custom (primogeniture).

At the age of eighteen, circa 1904, he decided to immigrate to America and landed in Seattle, Washington. While it’s not known exactly why he came to the United States it is probable that he had heard of the opportunities here. His first employment was as a railroad laborer but found that the work was too strenuous for his slight body and became a dishwasher. Working in the kitchen, he learned to cook and became a cook, which was a relatively high paying occupation for a recent immigrant. Throughout this period and later on he sent part of his earnings regularly to his parents in Japan.

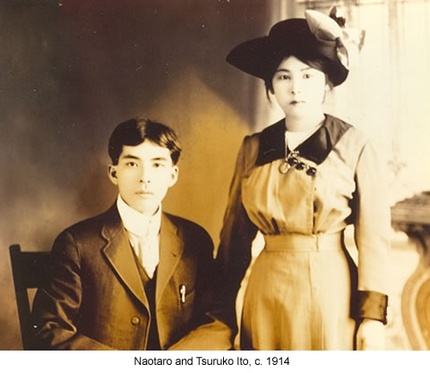

In 1911 he had saved enough to buy a hotel, which prospered enough to support his younger brother Tokujiro, a student at the University of Washington. It also enabled him to think about marriage. An older woman named Mrs. Kawaguchi who worked at the hotel as a housekeeper told Naotaro about a young woman who lived in her home village and whom she personally knew from childhood that would be a very good marriage prospect for him. After viewing a picture of the young woman, Tsuruko Yoshioka, and corresponding with her and her family, Naotaro decided to go to her village in Ehime Prefecture, Japan to marry her.

Tsuruko Yoshioka was born in 1896, one of several children in her family. Her father, Gentaro was a fish distributor dealing with markets in Osaka and Kobe. They lived in Mitsukue, a thriving fishing village on the southern-most tip of the island of Shikoku. Unfortunately he passed away when Tsuruko was in her early teens, leaving her mother a struggling widow. This may have been one reason that the family accepted Naotaro’s marriage proposal since he was thought of as a prosperous hotel owner from America. So in 1914, Naotaro arranged to go to Japan for the first time since his arrival to America in 1904.

Since Naotaro was going to Japan for an extended stay, he left Tokujiro in charge of his hotel during his absence trusting him with power attorney. Naotaro went to Mitsukue dressed in a white suit and shoes and a Panama hat. His arrival was long anticipated by the entire village— so much so that the arrival was a very festive event for the villagers. As his ferryboat approached the village with him on deck, the villagers cheered him as a visiting celebrity as the boat docked. After their marriage in Mitsukue, the couple went to Kitsuneji to see Naotaro’s family. Naotaro recalled this visit as particularly joyful to his father who introduced him to his friends, especially his drinking companions as his very successful hotel owner son from America (his father was a devout Buddhist but also an indolent alcoholic with many drinking companions). As a probable reaction to his father’s alcoholic lifestyle, Naotaro and all of his siblings were lifetime teetotalers. Another fond memory of this trip home of which he spoke often to his children, was that his mother would check each night to see whether he was covered with blankets once she thought he was asleep. This was clear evidence to him that mothers would care for their children no matter how old or independent they became.

After his triumphant trip home, upon his return to Seattle, Naotaro found that Tokujiro had lost his hotel and all his financial assets in a foolish business venture during his absence. He soon learned that most of the people that he considered his friends abandoned him and that he had nothing with which to start over. Considering his disastrous circumstances, he asked Tsuruko to return home to Japan until he could work and save enough to start a new business to support her. Tsuruko being a very proud woman strongly opposed this. She said that returning to Mitsukue under the circumstances was haji (shameful) and would be humiliating to her and her family. She wanted to stay with Naotaro and work along with him to save enough to start over. The very thought of her returning home and facing the villagers was unthinkable to her.

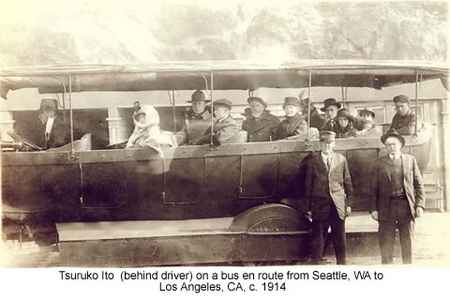

Naotaro heard that work was available in California, so he and Tsuruko decided to leave Seattle for a new beginning in Southern California. After a short stop in Los Angeles they went to Riverside to work in a packinghouse for oranges. Living quarters there were very primitive and intended for bachelors only and Tsuruko was the only woman present. To add to their difficulties, Tsuruko was pregnant and gave birth to a daughter, Yoneko. Bathing was a particular nightmare for Tsuruko. Everyone had to share a single Japanese bath, which meant that some twenty men would have been in the bathwater before Tsuruko and Yoneko could use it. (According to Japanese custom men came first in turn before women and children.)

After the orange crop season was over for the year, Naotaro and Tsuruko found more permanent work in the fish canneries on Terminal Island in San Pedro. Having found a neighborhood woman to care for Yoneko, both Naotaro and Tsuruko worked. Tsuruko was very adept at cutting and dressing fish since she grew up in a fishing village where fish was abundant. She often teased Naotaro that she made more money than him during this period because of her skills in dressing fish.

After a year had passed, Tsuruko became pregnant again. Both Naotaro and Tsuruko realized that they could not reach their goal of financial success at the rate they were going. Naotaro convinced Tsuruko that he would have a better opportunity to save enough to start a business if Tsuruko returned to Japan with Yoneko and have the new child in Japan. The plan was for her to go to his parent’s house, give birth to the new child and remain in the care of his family until he called her to rejoin him after he got back on his feet.

Once she got to Naotaro’s family home, she found family relations intolerable. Worst was Naotaro’s older brother’s arrogant wife and her son who committed constant acts of cruelty to defenseless Yoneko who was still a young toddler. Although Naotaro’s mother was sympathetic, she was unable to correct the situation and sadly accepted Tsuruko’ s decision to return to her mother’s house in Mitsukue.

Tsuruko stayed with her mother and gave birth to another daughter, Hideko. As the months passed, she became more and more impatient to return to America. Although Naotaro sent her money regularly, he seldom wrote of his progress, and she suspected there were other women on the scene. When Hideko was eighteen months old but not yet weaned, Tsuruko decided she could wait no longer and asked her mother if she could leave the children under her care to which her mother consented. The night of her departure was the most difficult experience in her life. She put Yoneko and Hideko to sleep and quietly left the house, but after walking a few hundred yards she deeply regretted leaving and hurried home intending to stay. When she opened the door, her mother firmly motioned to go and told her to not worry about the children and that she should do what she had to do.

On her journey to America, her breasts constantly congested with milk and became very painful because Hideko had not been weaned before her departure. During the long trip she was constantly in tears. When the ship finally arrived in San Pedro Harbor, there was no one to greet her because word hadn’t reached Naotaro of his wife’s coming. Tsuruko boarded a bus to Los Angeles not knowing exactly where to go. The bus driver left her off at stop nearest to Japantown and pointed the direction she should go. Finally she reached the hotel where Naotaro was living and knocked at the door. Needless to say, Naotaro was completely surprised since he was not expecting her at all.

© 2008 Roy T. Ito