In cultural creations ranging from outdoor gardens to works of art, music and literature, the question of authenticity often captures the attention of scholars, critics and laypeople alike. As a nation long known as the land of opportunity, the United States symbolizes a place where one can reinvent his or her life and start anew. Neither bound nor bolstered by thousands of years of national tradition, it is not surprising that Americans reinvent not only themselves, but numerous cultural creations brought over from other nations by immigrants and tourists alike.

In the case of Japanese-style gardens in the United States, the imitative process operates on both literal and representational levels. The most telling part of this process is that it is regarded by patrons and visitors as imitation with the aim of cultural authenticity, but ends up being a translation from one cultural language to another that is entirely different. In the words of historian Virginia Scott Jenkins, “A new landscape aesthetic is a new cultural creation,” and the Japanese inspired garden in America is just that.1 We often think of American innovation and experimentation in the domain of business and technology, but this spirit also manifests itself in our relationship with the natural world. In Japanese-style gardens in America, imitation becomes a reinvention of nature – rather than a corruption of it—and accordingly, the reinvented garden becomes part of American culture.

Established in 1894 as part of the city’s Mid-Winter Fair, the Japanese Tea Garden in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park has experienced as much change over time as the city itself. In 1910, just four years after a devastating earthquake and fire ravaged most of the city, San Francisco renewed its campaign to host the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915. According to the promoters of the exposition, “There is a magic in the very name California. In every hamlet on the continent are people who look forward to visiting California. They have heard of its scenic wonders, its balmy climate, and abounding industries. They know it is as the land of plenty.”2 Many of these legendary qualities led Japanese immigrants to settle in the Golden State in the 1880s. The exposition itself was a great public success, and structural elements from the popular Japanese Pavilion, including the torii gate, pagoda, and temple gate (all adjacent to the main pond), found a permanent home in the Golden Gate Park.3

During the early decades of the twentieth century, first-generation Japanese immigrants, the Issei, had a great impact upon California’s agriculture and the greening of the state. Through their extensive work in farming, maintenance gardening and, to a lesser degree, garden design, they established a niche for themselves in matters pertaining to the soil. Much like the residents of San Francisco who rallied successfully to host the 1915 exposition, they were “imbued with the Western spirit of success.”4 Roughly one hundred years later, very few Japanese Americans till the soil of their grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ farms. The profession of gardening, once synonymous with the Japanese American community in California, now employs steadily decreasing numbers of gardeners with each passing year as the aging Nisei retire.

These significant shifts prompt one to question what remains of this history so intimately tied to the soil. Where might one look to find the legacy of these early immigrants and their Nisei children? The most enduring public (and not coincidentally, the most popular) legacy of the early Japanese American community is the Japanese-style garden. Throughout the nation and around the world, people from all walks of life continue to enjoy, contemplate, and create such gardens. In America, this popularity has sometimes waned but never disappeared entirely. Given the longstanding fascination and history that European Americans have with all things Japanese, it is unlikely that it ever will.

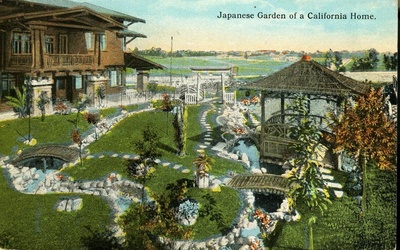

Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century World’s Fairs and expositions introduced millions of Americans to Japanese-style gardens. These much-heralded gardens also included tea houses, pagodas, pavilions and arched bridges to showcase not only the architectural beauty of Japan, but to educate Americans about Japanese culture. In an era of intensifying anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States, the Japanese government-sponsored displays at World’s Fairs and expos offered a prime opportunity to showcase a peaceful and serene image of Japan. But despite the popularity of the gardens and cultural displays, anti-Japanese legislation had a severe impact upon Issei immigration and livelihood in the United States. The Gentlemen’s Agreement (1908), California’s Alien Land Laws (1913, 1920, and 1923), and the Immigration Act of 1924 presented unique challenges to persons of Japanese ancestry living in the United States as well as those who yet wished to immigrate from Japan.5 World’s fair visitors and the largely European-American public remained enchanted with the gardens long after the fairs ended, and it was this fascination with all things Japanese that inspired the design and creation of hundreds of both private and public gardens across the country. From the American West to the Midwest, South and East Coast, such gardens gained in popularity as they mimicked the expo gardens, regional tastes and evolving ideas about what an “authentic” garden should encompass.

Beyond the tastes and preferences of patrons and garden designers, regional variations in climate greatly influenced and continue to shape the particular look and character of the Japanese-style gardens. For example, the Pacific Northwest most closely approximates Japan’s misty, rainy climate. Consequently, lush, verdant moss is planted to great effect in gardens such as the Bloedel Reserve, Bainbridge Island, Washington. Moss can be used in other, more arid climates, but would require diligent misting and watering in order to maintain the integrity of the moss.6 Substitutes such as moss sandwort (Minuartia verna), which grows in full sun and light shade, or flowering moss (Pyxidanthera barbulata) can be used more easily in many other parts of the United States.7 Neither is a true moss, but the substitution of these “inauthentic” plants does not diminish the intrinsic value of the garden. The visual effect produced by these moss-like species gestures toward the “authentic” garden in Japan while creating a distinctly American garden. Similarly, evergreen trees and shrubs widely used in Japan include varieties of azaleas, camellias and gardenias, but regions in the United States with extreme winter temperatures (below 0 ° F) cannot incorporate these plants unless dedicated gardeners wish to replant them each year. Therefore, plants including hardier rhododendrons, as well as species of abelia, pieris, mahonia, and ilex have become part of Japanese-style gardens in Illinois, Michigan and other parts of the nation that commonly experience subzero temperatures.8 This adaptation of garden flora underscores the American spirit of inventiveness which has long been intertwined with American history. Showcasing this translation of culture within the confines of Japanese-style gardens allows for the inclusion of American regional differences while maintaining elements of Japanese aesthetics.

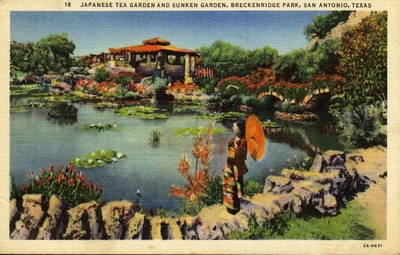

As early twentieth century tensions continued to flare between the United States and Japan, the history between the two nations was forever altered when Japanese military forces attacked Pearl Harbor. Many Americans now know of the United States government’s decision to incarcerate en masse all Americans of Japanese ancestry who lived in the “restricted zone” of the western states. Few realize the impact that this atmosphere of racism and distrust had upon the environment. Japanese-style gardens in America gained in popularity from the 1890s through the early 1940s, but with the outbreak of war, some gardens that were considered en vogue for decades prior to December 7, 1941 were destroyed without ceremony. Overton Park in Memphis, Tennessee held one such unfortunate case. Originally constructed in about 1905, the Memphis garden succumbed to the bulldozer in January 1942.9 Other more fortunate Japanese-style gardens suffered only isolated damages of garden structures and plants. In the wake of the sudden unpopularity of all things Japanese, many gardens underwent a name change until tensions abated in the postwar era. For example, the famous Japanese Tea Garden at Golden Gate Park became the Oriental Tea Garden until 1952.10 (Perhaps not so coincidentally, that was also the first year that Japanese nationals were legally permitted to become naturalized United States citizens.) The Japanese Tea Garden and Sunken Garden at Breckenridge Park, San Antonio, Texas was known as the Chinese Sunken Garden. Such identity changes of gardens in America were typical for the time period. The United States government forced the majority of west coast Issei and Nisei into an exile of public invisibility for the duration of the war; semantics was America’s way of erasing Japanese-style gardens and their cultural contributions to the United States.

During the post World War II era, Japanese-style gardens experienced a renaissance in America. This may seem illogical given the intense anti-Japanese fervor both before and during the war—a combination of fear and racism which directly impacted over 110,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry—but by the war’s end most Americans, regardless of their racial or ethnic backgrounds, were tired of the destruction and looming uncertainties that went hand-in-hand with the so-called “Good War.” The military might of Japan was no longer a threat to America, so although the Issei and Nisei were certainly not embraced by all upon their release from the concentration camps, Japanese-inspired gardens once again filled a need for serenity and natural beauty in the mainstream American public. Again, Japanese culture and aesthetics were viewed as being quite different from the people of Japanese ancestry in America. In the postwar era and increasingly so in the present day, quick escapes to Japanese-style gardens temporarily provide a space of repose and reflection so often lacking in modern times.

Intimately connected with the natural world, Japanese-style gardens composed of everything from evergreens to stones, water, bridges and ornamental elements transport visitors to a place which seems far removed from the pressures of city life. With an ever increasing human population in the United States, urbanites and suburbanites often find themselves yearning for day-trips to the country, woods, mountains or beaches in order to reconnect with that contemplative side which is all too often obscured by the stresses of daily work and outside responsibilities. As concrete and asphalt take over so many downtowns and cities across the country, gardens are even more essential to maintain a balance between the built and natural environment. Despite the fact that Japanese-style gardens are human creations, they subtly mimic nature beyond the obvious usage of plants, ponds, and pebbles. For example, ”vertical, jagged, angular rocks allude to mountains, cascading streams, and waterfalls; lower, rounded, smoother rocks give a sense of valleys with rivers and slower streams.”11 Raked gravel and sand, commonly associated with Zen Buddhist-influenced gardens, is styled to evoke all manner of water from tranquil ponds, to meandering streams, to breaking ocean waves. Tamazukuri, the rounded pruning style, is used to great effect with certain species of evergreen, as well as with dwarf Japanese holly, boxwood, and dwarf Mugo pine, all of which are naturally rounded plants.12 The pruned shape of the plants mimics the presence of floating clouds, mountains or stepping stones which lead the eye to another visual element in the garden. Even nature imitates nature.

The United States of America, long known as the land of opportunity to millions of immigrants, appeals to that sense of entrepreneurship and determination that lies at the heart of so many dreams for a better life. In the case of Japanese immigrants, thousands headed east to America and settled in the West. But America is not just a place where immigrants seek to expand their fortunes and have a hand in their own destiny; native-born Americans of all ethnic backgrounds set out for the West Coast, the Eastern Seaboard, and all points in between in order to reinvent their lives. Inventing or reinventing one’s life has long been a large part of the appeal of the United States. It is no wonder that a nation with such a reputation should spawn not only the reinvention of people but also of the cultural traditions and natural processes that have come to define America. Not every state in the union houses a Japanese-style garden, but as urban areas become more populous and as increasingly overwhelmed people lament how quickly the hours in the day hasten past, Americans will turn to renew their personal ties with nature, broadly defined, in order to negotiate a balance in their lives. It may be something as simple as taking an afternoon stroll down a tree-lined street in the city or as involved as reinventing Thoreau’s experiment at Walden Pond. However you choose to do it, do not allow yourself to be bound by cultural traditions in nature. Be inspired by them instead.

Footnotes

1. Virginia Scott Jenkins, The Lawn: a History of an American Obsession (Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994).,87.

2. Facts for Boosters, Issued by the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, San Francisco, 1910, pp.4.

3. Melba Levick and Kendall H Brown, Japanese-style gardens of the Pacific West Coast (New York; Rizzoli, 1999).,39.

4. Facts for Boosters, 32.

5. The Gentlemen’s Agreement prevented the immigration of laborers from Japan; the Alien Land Laws collectively barred Issei from owning, leasing, or cultivating agricultural land; and with few exceptions, the Immigration Act of 1924 disallowed large-scale Japanese immigration to the United States until the Immigration Act of 1965 abolished national-origin immigration quota

6. Maggie Oster, Reflections of the Spirit; Japanese Gardens in America (New York, Dutton Studio Books, 1993).,208,211.

7. Wendy B. Murphy and Time-Life Books., ”Japanese gardens,” (Alexandria, VA, Time-Life Books, 1979).,61.

8. Oster, Reflections of the Spirit: Japanese Gardens in America.,196.

9. Levick and Brown, Japanese-style Gardens of the Pacific West Coast.,23-24.

10. Ibid.,36.

11. Oster, Reflections of the Spirit: Japanese Gardens in America., 132.

12. Ibid.,220.

* * *

Related links: "Japanese Garden postcards", an online collection of vintage postcards created by Carla Tengan on Nikkei Album.

* * *

© 2007 Carla Tengan