Tomás de Gonzada Street in the mid-1970s: flashy neon lights, Japanese men drunkenly staggering and stumbling out of a club entrance, and the lovely voices of hostesses, with heavy make-up, waving goodbye. With sundown, Oriental town would transform itself into an amusement quarters.

As mentioned before, there were three factors in the re-gathering of the Nikkei population and constructing of Oriental town in post-war Liberdade District. These included 1) the establishment of the Cine Niterói in 1953, 2) the founding of the Brazil Japanese Culture Association Center Building in April of 1964, and 3) the opening of the Liberdade subway station in September of 1975. A further factor in the development of the area, especially in São Paulo, was the entrance of Japanese businesses into the Brazilian market in the 1970s and 1980s. At this time, Oriental town functioned as a pleasure quarters for residing Japanese businessmen as well as a market for purchasing Japanese ingredients and products. As a result, these businessmen and their families became a large consumer population for Oriental town.

In the background of such Japanese business advancements, Brazil was also experiencing economic growth and prosperity. Between 1968 and 1973, there was a rapid growth in the Brazilian economy and GDP growth reached 11% a year. Foreign businesses found the Brazilian market welcoming, resulting in many foreign companies making inroads in Brazil. Due to efforts of the government to introduce foreign capital in the country, large investments were made to consumer goods and the capital goods industry. Much of Brazilian infrastructure, such as electricity and communication methods, was established in this period. Further, numerous large-scale national projects were implemented, creating a prosperous time later referred to as the “Brazil’s miracle” (80 Year History, p.262).

Japanese business advancements in Brazil also grew rapidly. Japanese manufacturing industries which entered into the Brazilian market at the time included Taiyo [NT: actually Maruha], Ishikawajima Industries, Kawasaki Industries, Howa Industries, Toyobou, Pilot, Ajinomoto, Nihon-reizo, Yanmar Diesel, and Kubota Ironworks. Japanese general trading companies and banks included Mitsui-Bussan, Mitsubishi-Shoji, Bank of Tokyo, and Sumitomo Bank. During the peak from 1977 to 1980, it is estimated that there were over 500 Japanese companies in Brazil (80 Year History, p.263).

A large portion of these businesses held their main offices in São Paulo with the company staff living in the city. Oriental town, which was in the process of further development, functioned as a market for Japanese daily-use products and cooking ingredients for these Japanese company workers and their families, offered services as a pleasure quarters as well.

Otami Kanda, former-chief editor of Nippaku Mainichi Shimbun (Brazilian-Japanese Mainichi Newspaper - the later Nikkei Newspaper), reminiscing about the early Japanese business advancements at the end of the 1960s, wrote (though long, I believe it reflects the atmosphere of the day well):

There was a time when the staff of the big-companies, who had recently come over from Japan, would be drinking at the bars in the Liberdade district and repeatedly comment rudely that “there’s something missing about the Japantown of Brazil.” The former-local news reporter of the Yomiuri Newspaper and a frequent writer of non-fiction, Mr. H, who had come to Brazil around the end of the 1960s, had heard these comments and become very aggravated. “What an excuse!” he shouted as he stood up and encroached on them as if to throw in some punches. Mr. H had wanted to say that “the first immigrants had worked so hard to get to where they are now. What do you know!?”

So then what does “something missing” refer to? 1) all the other costumers and staff in the bar look as though they are impoverished, 2) the restaurants and even the general stores are far from stylish, 3) the new movies playing at the Japanese movie theater are half a year behind Japan. On top of that, people are happily watching these movies as if they are movie premieres. And the list goes on. The Japanese businessmen probably wanted to say that everything was “behind” in Brazil. At the time, Japanese restaurants had spread all the way to the Brigadeiro Luis Antônio Avenue neighborhood but were mostly concentrated in Liberdade. Hostesses were mostly from the Issei Nikkei population. Conversation could be done with only Japanese. You could simply drink quietly if with an Issei. This was a big deal since it was such a pain being told you were a strange customer if you didn’t make conversation. There was no trouble or hesitation if both the bar staff and customers were Japanese. Even if you went outside drunk, it wasn’t as if a trombadinhas (quote note: refers to a mugger) was going to rob you. There weren’t any worries about “bad public safety” in these times. Though the newly immigrated Japanese businessmen had said “something [was] missing,” the bars in those days were the best place to relax and rest after a hard day’s work (ACAL, 1996, pp.35-36).

Though referred to as “something missing” and “far from stylish,” Liberdad’s Nikkei business area was where these Japanese business workers would eat, drink, and relieve their stress. In a time when there were no home movie players, internet, or satellite TV, sake and movies were the only forms of after-5 (after work) entertainment. Contrarily, it could be said that this “far from stylish” area with “something missing” was actually where these workers would spend much of their time and money. Kanda continues to say,

In September of 1968, Cine Niterói on Galvão Bueno Street was demolished and moved to the Iguapé neighborhood. Even after Galvão Bueno Street was tuned into a highway, there was still an atmosphere in which one could relax and de-stress. After the mid-1970s, the restaurants and bars began to change. The Issei began to steadily withdraw from nighttime work. The situation being that their age began to be unfitting for such work. The retirement of hostesses who could speak only Japanese and the emergence of karaoke were relatively in the same time period. Bars were quickly in a frenzy to set up karaoke machines and people who were unable to speak fluent Japanese began to be hired as staff. Besides people who like karaoke, this change may have caused some to distance themselves from the area (ACAL, 1996, pp.35-36).

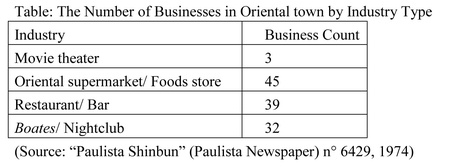

As mentioned before, in the latter half of the 1970s, the number of Japanese businesses in Brazil had reached its peak. Not only were there the businessmen of the Japanese companies, but also their families as well as people on business trips and visiting guests. In accordance with this, the number of businesses in Oriental town grew and the types of industries diversified. The next table shows the number of businesses by industry in 1974, the year the Association of Commerce and Industry of Liberdade was established and the birth year of Oriental town.

The table displays the neighborhoods function as a Japanese ingredients and products market as well as a nighttime entertainment area with restaurants, bars, boate, and nightclubs. “Gekkan Século” (Photo 1) was modeled after Japanese weekly magazines and was a unique Japanese monthly magazine published from the mid-1970s to the early 1980s. As the 1978 bonus volume, “Bessatsu Século:Burajiru Nikkei Inshoku Dai-tokuhon” (Bonus Volume Século: Brazilian Nikkei Dining Reader) was published on January 31st, 1978. In this magazine, it stated that Nikkei restaurants and bars were concentrated in the three areas of the Liberdade District, Brigadeiro Avenue and Paulista Avenue, and estimated there were around 300 businesses (p.14).

According to this magazine, the night life of the Japanese business workers at the time involved: dining in a Japanese restaurant in Liberdade (Oriental town), going directly after to a reasonably priced boate/nightclub in the area or venturing to a high class hostess club in the Brigadeiro Avenue neighborhood when one had the money. The “boate” mentioned here can be thought of as a type of nightclub, but the women who gather in the club are not staff but are generally treated like “customers.” In other words, the clubs do not pay the women a salary but function as a socializing place for women to “freely make relationships” with the male customers. In Brazil, it is more common to refer to this type of business as a boate than a “clube noturno” (night club). Between the mid-1970s to the 1980s, there were many clubs and boates in Oriental town run by “Mama-san,” Nissei women who could speak Japanese. This is way, Oriental town in this period was strengthening its characteristic as a dining and entertainment area for the businessmen of Japanese industries in Brazil.

References

Nihon imin 80nen shi hensann Iinnkai (Editing Comittee for 80 Year History of Japanese Immigration) (1991) Burajiru Nihon imin 80nen shi (80 Years of History of Japanese Immigrants to Brazil) São Paulo, 80 Year Immigration Celebration Committee

Paulista Shimbun No. 6429, 1974.

Bessatsu Século: Burajiru Nikkei Inshoku Dai-tokuhon (Bonus Volume Século: Brazilian Nikkei Dining Reader) . Século Shuppansha, January 31, 1978.

ACAL(1996)Liberdade. ACAL

© 2007 Sachio Negawa