Almost every day, as she walked to school through the old section of Chorillos, Peru, Gabriela Shiroma could hear the drums, calling in the voice of Africa. Their rhythms floated through an open window and into the street, their deep chorus reverberating within her chest and flirting with her own heartbeat. She knew she shouldn’t listen, but she always did.

“I always would wonder what was happening in that house, but I was forbidden to find out. I was raised with the mentality: ‘don’t get involved with Peruvians,’ especially blacks. But every time I heard the drums I loved it. I felt so motivated to dance, which I wasn’t supposed to do either.”

She spent years searching for a place to belong, to be of service. She traveled across continents, from Peru to the United States and back again before realizing “who I am is the sound of the drum.” Today, she lives in Alameda, California and is dance director of De Rompe y Raja, an acclaimed performance troupe dedicated to preserving the traditional African music and dance of her native Peru.

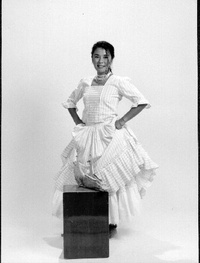

The descendant of Okinawans immigrants, Shiroma seems an unlikely crusader for the traditions of a continent far removed from her own history. To see her on stage, however, is to understand how the motivation of the heart transcends race, culture and expectations. When the wood box drum known as the cajon issues its opening chant, accompanied by the beat of congas and rattling teeth of a quijada de burro (donkey’s jawbone), De Rompe y Raja’s dancers become a moving mass of color in eye-popping red and blue colonial costumes. In the center, Shiroma whirls in an uninhibited rumba, playing a syncopated beat on a small wood drum, the cajita.

“I have come to understand there are many types of identity,” she says. “There is your public identity, your social identity, your civic identity and there is what is in your soul. You don’t have to look a certain way or come from a particular place to do what you have to do; you just have to follow the essence of your heart. I know there is something stronger out there that guides the mission of my life: to preserve Afro-Peruvian arts.”

Her parents emigrated with their families after World War II, arriving first in Brazil and then settling near Lima, where they met and married. “The Japanese in Peru were a closed society,” Shiroma says. “They had their own schools, stores, theaters. They helped each other and became a strong economic force, but they kept out of Peruvian society.”

Her father owned several furniture stores; when Gabriela and her four siblings were teens, her mother opened her own business, a “bazaar,” a small shop “where you can find a little of everything,” Shiroma says. They lived in a predominantly black neighborhood, but Shiroma attended the American high school. “My school was one of the richest in the area. It was like living in another part of the world—white, American and high class. But I could also see the richness of Peruvian culture in the streets—dogs fighting, people stealing, everything happening at once.”

When she was 15, a Peruvian friend invited her to a peña, a party with music and dance. “Of course I was prohibited to go, but I went anyway. I decided to learn the dances, so I took classes. That caused a lot of problems with my parents—they wanted me to be a secretary or a housewife.” At 17, she left home over her parents’ protests to study journalism, then moved to Argentina and switched her major to psychology. “I had so many conflicts inside, I couldn’t decide what I wanted to do,” she says.

In 1989, she joined a sister who’d moved to Santa Clara, California, and enrolled in graphic art classes at San Jose State University. “Everything kept pushing me toward music,” she recalls. “I kept walking by the dance department on the way to class, so finally I signed up for dance class. My first job was as a hostess in a karaoke bar. I had to learn Japanese songs, and of course I didn’t speak Japanese. All night long I had to sing, but all I really wanted to do was dance.”

Finally, she talked the bar manager into letting her stage a floor show. The club paid for polka dot dresses for her troupe of friends, and the applause helped her make up her mind. Switching classes yet again, she became a teacher’s assistant in the dance department and was hired to teach Afro-Peruvian dance at Stanford University. She taught on the Georgia Sea Islands and in Ghana. In 1995, she organized De Rompe y Raja. The group’s repertoire of original music and choreography, as well as revivals of traditional dances such as lando, festejo and zamacueca, immediately won a spot in the San Francisco Ethnic Dance Festival, and they’ve appeared regularly in that line-up since, in addition to frequent Bay Area performances.

“Every vacation I go back to Peru to work with the masters and to learn more,” she says. “I think about how much Africa has contributed to American culture, yet the Africans born here could not keep their language and religious traditions,” she notes. “With the effect of globalization, modernization and the small population, African culture will die in Peru, too, unless we keep it alive.” Her pursuit of dance has taken her to Mexico, Uruguay, Brazil and Togo. “I also went to Japan, to see the other part of me,” she says. “Then I understood the silences of my parents and grandparents. When you share a culture, you don’t have to speak so much. I understood the smells I grew up with—the miso soup, fish and pickles my grandfather ate every day. I have struggled for my identity, but now I’m very proud to be a descendent of Japanese culture. I have the same perfectionist goals, the annoying sense of organization they have, and the respect for the culture. If there is one thing that makes Japanese anywhere in the world different, it is that sense of honor. It drives me to make people aware of the biggest injustice that’s ever happened in the world, and that is slavery.”

Art, Shiroma believes, can effect change in lasting ways “because the point of view gets to you through your soul.” Her own journey began by listening to the message of the drum, and she is willing to go wherever it leads.

“Sometimes I listen to Afro-Peruvian music and I start crying. Why? I couldn’t stay away. I always try to do what I think I want to do and not what I’m supposed to do because I’m this, that or the other. I went here and there to find myself, and the only place I could find myself is inside of me. I’m proud to carry the cajon with me. It’s like my flag.”

* This article was originally published in Nikkei Heritage vol. XVI, no. 2 (Summer 2004), a journal of the National Japanese American Historical Society.

© 2004 National Japanese American Historical Society