Items of Japanophilia

|

||

| Licensing | ||

Building a Japanese Community Online

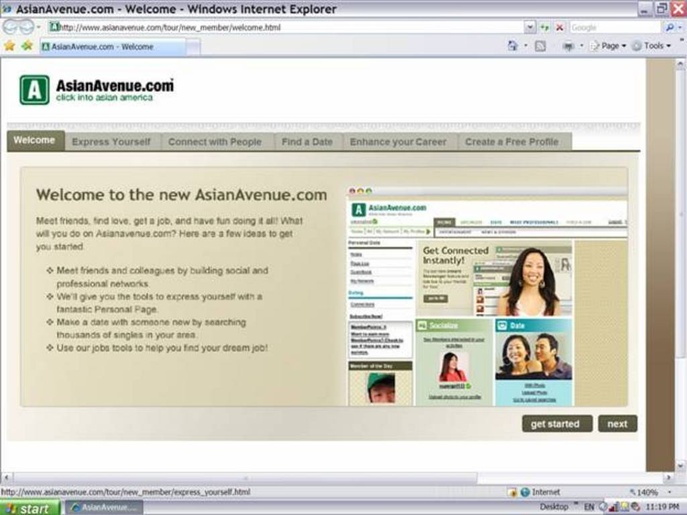

In addition to the Discover Nikkei website, which offers an extensive collection on Japanese-American resources and a community forum, there are other forms of internet blogs and web pages that create a Japanese community in America as well as in Japan. AsianAvenue, for example, is an old-time web blog that allows members to personalize their pages and network with other Asian-American members in English (though exclusivity to Asian-American members only is not specified). MIXI, a recent social networking service site in Japan, serves the same purpose as AsianAvenue in connecting friends through picture and file sharing. Joining MIXI, however, is limited to those who are invited from current members and, as it is a Japanese site, those who can read Japanese.

The various uses of web pages create a new Japanese community found online. Although members are not always Japanese or of Japanese descent, the internet provides a new community that connects people through common interests. The online community transcends physical boundaries and unites under an Asian avenue emphasizing individualism and group identity. The new Asian group identity represents part of the popular culture, internet savvy generation that replaces stereotypical notions of traditional Asia.

AsianAvenue allows members to personalize pages and to connect to professionals, such as entertainment stars, and potential dates. The subtitle under its trademark sign, “click into Asian America,” suggests a new world where members can express their individualism while rallying under a group identity as “Asian.” Although membership does not explicitly restrict people of non-Asian backgrounds, the name AsianAvenue implies networking for Asian-Americans. Becoming a member of AsianAvenue becomes a claim to or association with the Asian community. Members are proud of their cultural heritage by identifying a part of them that falls under the Asian avenue. From the group, members choose to express their individualism with diary posts and decorated backgrounds and pictures. AsianAvenue provides an outlet for members to voice their opinions and share stories that can receive comments and feedback from those of the same interest.

Through networking, users create a transnational identity between Japan and America—as well as Asia and America—that contrasts the identity of the issei, or first generation Japanese-Americans. Eiichiro Azuma, Professor of History and Asian American Studies, notes the collective racial identity process that issei experienced. In reference to the zaibei doho, or the emergence of a community of Japanese in America, Azuma comments that “what bound diverse groups of Issei was their shared experience of being a racial Other in America, which revealed the futility of the modernist belief that then Japanese should be able to become honorary whites through acculturation.” In contrast, AsianAvenue does not serve as a support group for minorities today, but rather an online space that fosters community under common interests and backgrounds. AsianAvenue does not promote members to change into “honorary whites” but rather absorb Japanese and American culture to form a unique identity, part of the bigger whole of the Asian community.

In the case of MIXI, the website is a community forum that is highly casual and informal. Members utilize the suffix “chan” when addressing their friends’ names and employ colloquial form when posting notes on their friends’ pages. The formal usage of Japanese language to distinguish a level of superiority and respect disappears as MIXI transcends class level and forges friendships instead. As a result, members create a new identity that is individualistic, as they can personalize their own pages, but also form under a new community influenced by and familiar of Japanese popular culture. Contrary to stereotypical notions of the humble and introverted Asian, MIXI members display their inner self and allow others to learn more about them. The “community” section also allows members to meet each other through common interests, such as in music, or television dramas, or even by company or school name. While claiming an individualistic identity on their own page, members also rally under a community, the MIXI community, which reinforces the Japanese community as a whole.

MIXI and AsianAvenue provide an online space for building a new Asian community popular among the younger generations, in particular. Participating in the websites serves as a form of Japanophilia, in which the member becomes engaged in displaying and exploring his or her identity as an individual and as part of the Japanese community. Members become obsessed with updating their profiles to show their present mood and personality. By finding friends that share common moods and personalities, members thereby reinforce their claim to the Asian community online.

Works Cited:

1)Eiichiro Azuma, Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America, New York:

Oxford, 2005, 62.

For those who wish to visit these websites, see the following below:

AsianAvenue: http://www.asianavenue.com/tour/new_member/welcome.html

MIXI: http://mixi.jp/about.pl

The Candy Mascot

The yatsuhashi maiko-san, known as Yuko, serves as a mascot promoting the candy. Dressed in a traditional Japanese kimono, Yuko conjures up an image of homeliness and comfort food that the traditional house wife is best at making. Yatsuhashi is a traditional sweet cookie that also comes in a raw form served with cinnamon. A famous souvenir from Kyoto, yatsuhashi is wrapped in a nicely decorated box with Yuko on the cover. The company of yatsuhashi employs the mascot as a marketing strategy suggesting nostalgia and comfort in traditional Japan. Yuko thus becomes an icon and form of cultural capital for Japan.

The company’s operations, which began in 1805, involve capturing and commodifying traditional Japan. The appearance of Yuko in traditional wear exoticizes and emphasizes Japanese culture as ancient and unique. Tourists—both foreign and Japanese natives—of Kyoto not only consume a delicious snack but also consume a representational part of Japanese culture. Anne Allison, a Professor of Cultural Anthropology at Duke University, mentions the popular marketing strategy that companies employ in the usage of play characters. Referring to, specifically, commodities of anime and video games, “play characters have become a popular strategy used by groups, products, and companies of various sorts to stake their own identity and differentiate it from that of others,” In utilizing the maiko-san,the yatsuhashi company has certainly done so in creating a unique logo. Although Yuko is not a toy created from anime or video games, she still serves as a Japanophilic image of a traditional Japan that caters to the older generation.

Works Cited:

1) Yatsuhashi,” http://www.yatsuhashi.co.jp/index2.html, April 2007.

2) Anne Allison, Milliennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006, 17.

For those of you who wish to visit the website, go to:

Yatsuhashi Yuko: www.kiosk.co.jp/miyage/kyoto/04.html and http://www.yatsuhashi.co.jp/index2.html

This work is licensed under a Public Domain

Album Type

other

knuibe

—

Last modified Jun 28 2021 1:49 a.m.

knuibe

—

Last modified Jun 28 2021 1:49 a.m.

Part of these albums

|

Japanophilia mpitelka

mpitelka

|

|

Items of Japanophilia

Items of Japanophilia Stoner Park Japanese Garden

Stoner Park Japanese Garden

Journal feed

Journal feed