Japanophilia, Minstrelsy, and Commodity Culture

|

||

| Licensing | ||

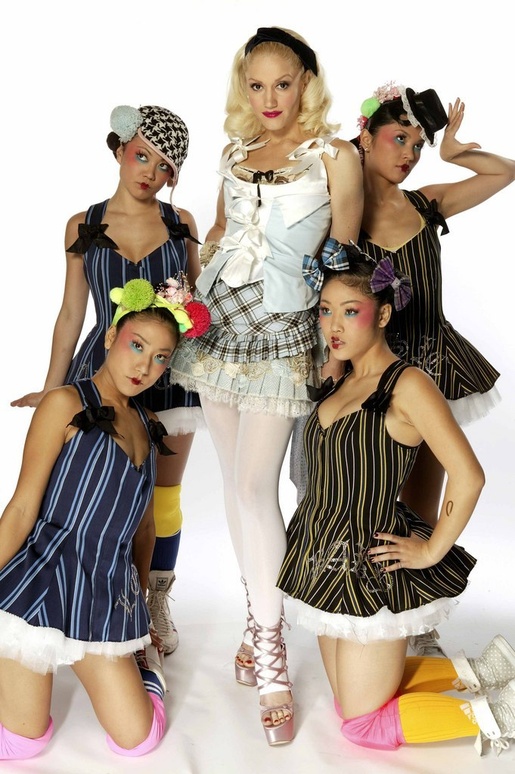

Japanese consumer products in the United States are highly prized for their cultural value. These Japanophilic products can serve as an escape into the land of the foreign Japan, or as James Clifford states, the “forbidden area of the self” (Clifford, 142). One form of these cultural products inspired by Japan are costumes or items that enable the consumer to play dress up and indulge his/her personal fetish of Japan. By being able to dress up as a racialized fantasy, individuals can fulfill their lack of self identity. In analyzing three types of Japanese costuming, a Geisha costume, a baby kimono, and Gwen Stefani’s Harajuku Girls dancing troupe, we elucidate the complex condition of Japanophilia as it reifies racial appropriation and minstrelsy. CostumeCraze.com sells a variety of costumes to become othered cultures; a buyer could dress “Arabian,” “Mexican,” “Indian,” or “Asian,” among others. There are 89 different costumes to dress up as “Asian” for all ages, genders, and body sizes. One costume that draws particular interest is the “Premier Geisha.” For $123.99, one of the more expensive costumes available, one can purchase the Costume Gown of a Premier Japanese Geisha. Perhaps the high price of this costume correlates with its pleasant “cultural fragrance.” According to Koichi Iwabuchi, author of Recentering Globalization, Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism, the cultural “odor” of a certain object is not “necessarily related to the material influence or quality of the product. It has more to do with widely disseminated symbolic images of the country of origin” (Iwabuchi, 27). Sanitized of any actual cultural relevance, this inauthentic Geisha costume allows the consumer to put on “yellow face.” The description of the costume reveals the stereotyping of Japanese women and geisha culture; it states that, “this beautiful, demure Premier Geisha Costume Gown includes the satin under-gown, Japanese floral brocade satin top coat with drop sleeves, waist sash & lace fan.” Essentially, one could dress in this costume in order to become the quiet, modest, and coy Japanese women. The positioning of the body and face in the photograph epitomizes the stereotype of the alluring geisha woman. In a similar fashion, the iPlay Baby Panda Kimono set gives parents the opportunity to dress their child in a Japanese-style baby outfit. Although advertised as a “kimono,” the outfit does not resemble a kimono aside from its wrap-like style. For $17.99, an outfit of a wrap-and-tie top with a pair of matching pants and a Panda printed on the top, a child can be fully outfitted as a Japanese baby. This baby outfit is a part of a whole genre of baby clothing that attempts to fuse comfort with culture, in this case all cotton-wear with Japan. James Clifford discusses how collections of cultural items, such as clothing, “create the illusion of adequate representation of a world by first cutting objects out of specific contexts…and making them ‘stand for’ abstract wholes” (Clifford, 144); for example, a baby kimono becomes a metonym for Japanese culture. This type of consumer product, along with the Geisha costume, illustrates the misrecognition of Japanese culture and the desire by consumers to become the fetish of the “other.” Gwen Stefani’s Harajuku girls epitomize the result of using the intersection of consumption and racist stereotypes to produce a franchise of products that profit from the fantasies of their customers. The Harajuku girls are a troupe of four singer/dancers, who were given names by Gwen Stefani, an American pop star. Their names are “Love,” “Angel,” “Music,” and “Baby,” named after Stefani’s clothing line and music album. These four women are dressed as caricatures of Japanese girls. Their identity is relegated to being demure, Japanese dolls. Furthermore, this identity performative—they are not allowed to speak in public or detract from their role. They simply pose for pictures and follow Gwen Stefani around during her public appearances. Drawing parallels to blackface and minstrelsy in the antebellum South, David R. Roediger, author of The Wages of Whiteness, argues that the content of the minstrel performances “identifies their particular appeals as expressions of the longings and fears and the hopes and prejudices” of those who watch and consume these performances (Roediger, 115). This is essential to understanding the Harajuku girls, their costuming, and the performance. By performing Japanese stereotype of the modest yet sexualized Japanese girl, these women enhance the cultural worth of Gwen Stefani, who uses the cultural value of Japan to fuel her music career and fashion line. In Millennial Monsters, Anne Allison discusses Sailor Moon characters and sexualized bodies in a section called “Fierce Flesh”; she writes that the Japanese “school girls” are depicted as material queens and consumer whores: as persons so fixated on consumption they are willing to turn their own bodies into sexual commodities” (Allison, 139). The Harajuku girls embody this image as they are often outfitted by Gwen Stefani to resemble this sexualized persona or as Allison calls it, a “fleshy reality” (Allison, 140). These cultural products and forms all use Japanese styles and images to benefit from racist stereotyping and minstrelsy. By using widely fetishized images of the Japanese culture, as misrecognized as they may be, each product serves to give consumers and voyeurs alike the ability to step into the forbidden realm of the other. These costumes and performative behaviors intrinsically relate to appropriation of culture and the creation of a fabricated self-identity. References Allison, Anne. Millennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination. University of California Press, 2006. Clifford, James. On Collecting Art and Culture: Marginalization and Contemporary Culture. MIT Press, 1990. Iwabuchi, Koichi. Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism.Duke University Press, 2002. Roediger, David. The Wages of Whiteness. Verso, 2000.

This work is licensed under a Public Domain

Album Type

community history

jessicasimes

—

Last modified Feb 08 2023 2:53 p.m.

jessicasimes

—

Last modified Feb 08 2023 2:53 p.m.

Part of these albums

|

Japanophilia mpitelka

mpitelka

|

|

Japanophilia, Minstrelsy, and Commodity Culture

Japanophilia, Minstrelsy, and Commodity Culture The Japanese Friendship Garden of Phoenix, AZ

The Japanese Friendship Garden of Phoenix, AZ

Journal feed

Journal feed