In a recent column, I described the detective work that I did to clear up a seemingly contradictory passage in a book by John Franklin Carter about Franklin Roosevelt's attitudes toward Japanese Americans. On another occasion, I had to deal with an even trickier piece of evidence that revealed FDR’s opinions concerning religious minorities. It required me not only to draw on my historical training, but on my experience working as a legal assistant.

The question first arose when I was doing research at the Franklin D Roosevelt Library on FDR’s signing of Executive Order 9066. One aspect of the President’s actions that I found particularly significant was his failure to plan for handling of the property of the Japanese community, and his refusal to ensure protection for the belongings of those excluded.

In my view, these were telling evidence of FDR’s malign indifference to the suffering of Japanese Americans, a weakness that marked (and tainted) his policy. While the government ultimately sent agents from the Federal Reserve to the West Coast to assist Japanese Americans in disposing of real property, and the Army and the War Relocation Authority provided some storage facilities for their belongings, Japanese Americans ultimately lost the vast majority of their property through forced sales, theft, vandalism, or spoilage.

As part of my study of the property question, I looked into the larger conflict within the Roosevelt administration over wartime handling of enemy aliens. Two of the president’s advisors, Leo Crowley, chair of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and Henry Morgenthau, Secretary of the Treasury, squabbled during the early weeks of 1942 over who should be given authority over handling enemy property. Their inability to agree on a division of responsibility further delayed official action in the leadup to mass removal.

Even after Crowley was appointed Custodian of Enemy Property in March 1942, the matter remained unresolved. Morgenthau refused to take on the thankless task of monitoring the property of the Japanese Americans, on the legalistic pretext that it was combined with the property of U.S. citizens.

In order to find more information, I consulted the microfilm of the Morgenthau diaries, which are a great source on the Roosevelt years for historians. Like several members of Roosevelt’s cabinet, Morgenthau kept a daily record of his time in office, and he further supplemented his personal reflections and records of his conversations with collected documents that his department put out. In looking through the diaries, I had a window into the chronology of the struggle over enemy property.

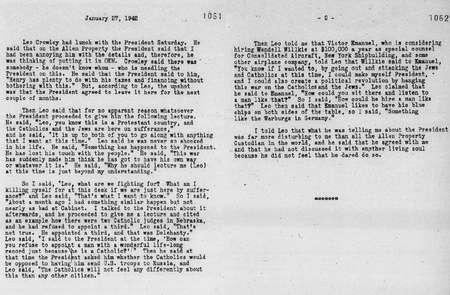

In reading through the diary for January 27, 1942, I found Morgenthau’s report of a meeting with Crowley. Crowley, an Irish American Catholic, related to the German Jewish Morgenthau that he had had a lunch meeting with the President, who had resisted making a definitive ruling as to whether the power would stay in Treasury with Morgenthau or go to Crowley via the Office of Emergency Management, but who then made a heavy-handed suggestion that the two rivals support whatever decision he made:

Then Leo said that for no apparent reason whatsoever the President proceeded to give him the following lecture. He said, ‘Leo, you know this is a Protestant country, and the Catholics and Jews are here on sufferance,’ and he said, ‘It is up to both of you to go along with anything I want at this time.’ Leo said he was never so shocked in his life. He said, “Something has happened to the President He has lost his touch with the people.” He said, “This war has suddenly made him think he has got to have his own way on whatever it is.”

Morgenthau related that he was equally horrified by such bigotry.

So I said, “Leo, what are we fighting for? What am I killing myself for at this desk if we are just here on sufferance?” and Leo said, “That’s what I want to know.” So I said, “About a month ago I had something similar happen but not nearly as bad at Cabinet. I talked to the President about it afterwards, and he proceeded to give me a lecture and cited as an example how there were two Catholic judges in Nebraska, and he had refused to appoint a third”…Leo said, “I said to the President at the time, “How can you refuse to appoint a man with a wonderful life-long record just because he is a Catholic?” Then he said that at that time the President asked him whether the Catholics would oppose him sending U.S. troops to Russia, and Leo said, “The Catholics will not feel any differently about this than any other citizen.”

After a brief side dialogue, Morgenthau and Crowley concluded their conversation and spoke of their mutual outrage and consternation over Roosevelt’s attitude:

I told Leo that what he was telling me about the President was more disturbing to me than all the Alien Property Custodian (sic) in the world, and he said that he agreed with me and that he had not discussed it with another living soul because he did not feel that he dared to do so.

After I came across this document in the archives, I wrestled with the question of whether and how I should treat its contents. On the one hand, it seemed to match the story I was telling.

Roosevelt was clearly conscious of the importance of handling alien property, and impatient with both Morgenthau and Crowley. Ironically, FDR’s efforts to get them to cease their conflict by playing on their ethnic backgrounds may have brought the two together, but in outrage over such sentiments.

On the other hand, I knew that such a document, which revealed FDR’s bigoted attitudes, would be explosive, and I was concerned about its reliability as evidence. It was composed entirely of secondhand and even thirdhand testimony, with only Morgenthau’s and Crowley’s word for both the remarks themselves and the context.

It seemed to me to fall under the rubric of hearsay. Just as it would normally be inadmissible in a court of law, I thought, should it not be inadmissible in a court of historical interpretation?

Fortunately, I had worked as a legal assistant in a law office, and witnessed trials. In the process I had become familiar with the hearsay rules. These provide a useful guide for judging evidence. Notably, direct statements were more trustworthy, precisely because they could be examined and rebutted in court. Yet I had also learned about exceptions to the rule, under which indirect evidence could be admitted. For example, one could testify to outside conversations to show a person’s mood or intent.

With this in mind, using inductive reasoning, I considered what factors might weigh in favor of the document’s authenticity and came up with a set:

-

The conversation between Crowley and Morgenthau was recounted around the time that it occurred, when memories were fresh, and in a confidential memo of a kind that encouraged frankness. Both men expressed genuine outrage over the president’s comments, and uncertainty and consternation as to how to respond.

-

Crowley and Morgenthau were both FDR loyalists and close advisers, without an independent base of support. Neither would have been inclined to invent shocking comments by the President they each served and admired, let alone repeat them in private conversations or diaries. Crowley's affirmation, given without prompting, that he did not dare tell anyone else what had occurred in his meeting with Roosevelt speaks to his desire to protect the President.

-

Crowley and Morgenthau were rivals for the job of Alien Property Custodian, and disliked (or at least distrusted) each other. Morgenthau considered Crowley a wheeler dealer and not very honest—he especially objected to Crowley drawing a salary from private sources while in government. Crowley considered Morgenthau power-hungry and interfering. Neither would have had anything to gain by falsely citing offensive statements by the President to the other.

Crowley surely knew that the Treasury Secretary kept records of his conversations, and that it would be easy for to him go back to Roosevelt and discredit him if he made a false claim. The fact that Morgenthau not only accepted Crowley’s account as a true record of Roosevelt’s words, but shared his own contemporary experience with the President, also promotes the credibility of the report.

I further took the liberty of asking advice from the distinguished Roosevelt historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., who had at one time worked for Morgenthau. Schlesinger in turn consulted the historian John Morton Blum, who had edited and published extracts from the Morgenthau Diaries. Both experts said that they were unaware of the incident described, but Schlesinger confirmed that the record seemed plausible for the reasons I had adduced.

In the end, I decided to cite the document briefly in my book By Order of the President, though without revealing my thinking process regarding its authenticity. Since then, I have seen the phrase about “sufferance” used by other researchers, who may have either read my account or found the text independently. In any case, with benefit of hindsight, I find that it is especially revealing.

The description of Franklin Roosevelt's expression of the idea that Jews and Catholics were in some essential sense not “really” American and equally deserving of citizenship matched his expressed attitudes about Japanese Americans during the 1920s, when FDR had publicly endorsed bans on Asian immigration and citizenship on the grounds that Asians were “unassimilable.” Such restrictive views also help explain why Roosevelt went along with demands from military leaders and West Coast political figures to remove ethnic Japanese from the West Coast in 1942.

© 2023 Greg Robinson