Sometimes it takes a soft-spoken woman like Kyoko Oda to use her charm to make sure the lives of 125,284 incarcerated Japanese American are not forgotten. Someone gentle on the outside but no less mighty on the inside as she works in multiple capacities calling attention to the lives forever changed by the mass detention. It can be seen in her work publishing her father’s Tule Lake Stockade Diary; working tirelessly on behalf of the Tuna Canyon Detention Station Coalition or the San Fernando Valley Japanese American Community Center; supporting ongoing projects like the World War II Camp Wall; or simply by climbing under a fence to collect soil at one of 75 detention centers featured along with the names of more than 125,000 former incarcerees as part of the monumental Ireichō book project.

Behind her impeccable white hair and rose-colored lipstick is a powerhouse who knows how to get things done, a skill perhaps honed over her 32 years as an elementary school principal. She’s learned certain tricks along the way, like making things beautiful as a way of attracting and inspiring others. Whether it’s proper stationery, an attractive book cover, or pretty dinner centerpieces, she insists that “everything be nice.” As the seasoned educator recalls, “When you’re talking to worn-out teachers, you want to help bring their energy up,” and she has wisely chosen to inspire and energize others with beauty.

Not fully realizing the power she wields, Oda prides herself on creating harmony in everything. It started with changing her name from Nancy back to her family name of Kyoko (originally spelled Kyouko by her father), which she says is translated as harmony or cooperation. As she visualizes it, “We are all shiny pebbles together on a desert island.” Everyone is slightly different yet much the same. Oda considers herself the “glue” that holds people and things together for the good of all.

She also has the sticky persistence to refuse to take no for an answer. For example, when the time-sensitive call went out from Ireichō project director Duncan Williams for soil samples from each of the 75 detention centers to be used to create a ceramic frontispiece to the sacred book of names, Oda volunteered to personally collect soil from not one, but from several sites, including Tuna Canyon Detention Station, Griffith Park Detention Camp, and the Kilauea Military Center.

After dragging her husband Kay along to these different locations, including traveling all the way to Volcano, HI, from her San Fernando Valley home, she found out that the project was still missing a soil sample from a former assembly center in the tiny town of Mayer, Arizona (pop. 1,847). She credits her ever-supportive and clever husband with combing the internet to find a local horse trainer, Phyllis Holmes, living nearby, who in turn found the oldest living resident of Mayer to help determine the exact spot where the detention center once stood.

Despite no connection to the people once imprisoned there, Holmes, a local historical enthusiast, was motivated enough by the former educator to go there to gather precious granules of Japanese American history. When it came time to ship the soil 380 miles to California where it was desperately needed before the public unveiling ceremony only a few weeks away, Oda convinced Holmes to package and send it by Federal Express because regular mail service was just not fast enough. Once more, Oda’s stick-to-it mission was accomplished.

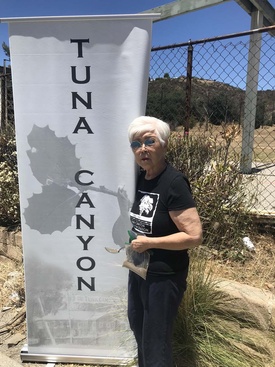

Oda’s unstoppable energy was seen again when she took on the job of getting soil from the Tuna Canyon Detention Station site, now occupied by the Verdugo Hills Golf Course. Because she was one of the leaders in the fight to win Cultural Historical Monument status for this little-known enemy alien camp, she knew a fence now encircled the site to protect the golf course’s driving range on the spot where the camp once stood.

Not to be deterred, she decided to climb under the stiff fence to retrieve the soil when a sharp piece of wire snapped on her arm causing it to bleed. By the time she realized that her arm was dropping blood everywhere, her only thought was to keep it off the large Tuna Canyon sign she was carrying to mark the occasion.

In a photo memorializing the event, a one-armed Oda can be seen carefully grasping two baggies full of precious dirt while hiding her bleeding arm as she held the spotless Tuna Canyon sign.

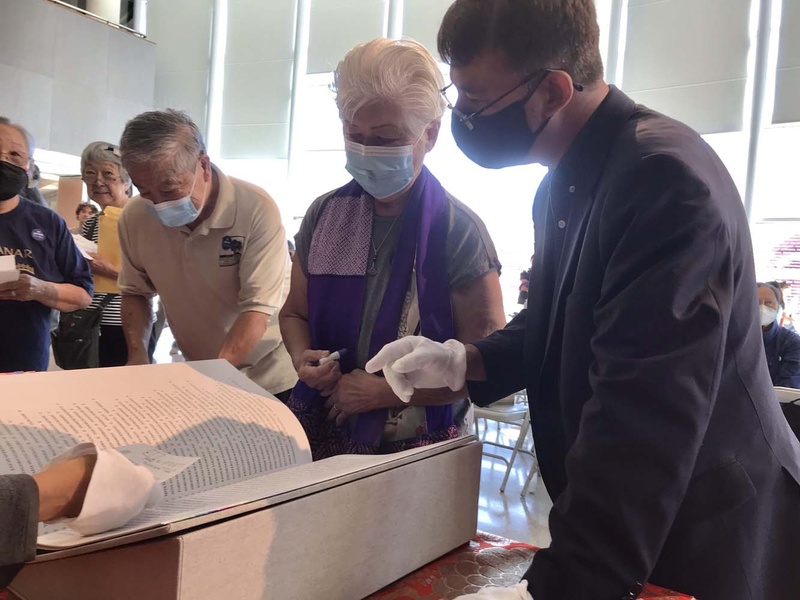

After gathering soil for Ireichō and feeling strong emotions at the unveiling of Ireichō in the sacred procession with clergy, community members, and supporters, on September 24, 2022, Oda knows there’s substantial work yet to be done to carry out other ways to ensure her ancestors are not forgotten.

One formidable project on her list is directly related to the Ireichō names project, i.e., the construction of a World War II Camp Wall in Torrance, CA, that lists more than 120,000 people on ten panels, each representing one of the ten War Relocation Authority sites. Comparing it to the acclaimed Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., Oda recognizes that their board faces many hurdles in moving this massive project forward, issues dealing with location, design, construction, security, parking, City Council approval, and much more. But as usual, nothing deters her from her mission.

She lauds the men she calls the “big thinkers”—visionaries like Ireichō project director Duncan Williams and Tuna Canyon Detention Station Coalition stalwart Kanji Sahara—as leading the way while downplaying the many essential roles she plays, referring to herself merely as a “worker bee.” But the most important organizational skill she provides is to bring people together and consistently work hard to forge a magical connection between those concerned with the injustices of the past and lessons for the future in a way that everyone understands.

It's only right that this newly self-realized “activist,” who once named herself “Nancy” after the popular cartoon character with a boyfriend named Sluggo, would reassert her birth name, Kyoko, after embarking on her crusade to honor her family history. After all, she was named by a father, who despite being falsely imprisoned in the infamous Tule Lake stockade, always maintained a vision of peace and harmony. Her wise parents obviously knew their daughter would one day grow up to be someone who quietly gathers the shiny pebbles in the sand to make it a more harmonious and beautiful place for everyone.

*All photos are courtesy of Kyoko Oda

© 2022 Sharon Yamato