Wakaji Matsumoto was like many of the young men, mostly teenagers, who came by transport ships from Japan to Hawai‘i, and then on to the western shores of Canada and the United States. He was seventeen when he first arrived in Vancouver in 1906, before making his way to Los Angeles by train to reunite with his father, whom he hardly knew.

When Wakaji was a toddler, he was left with relatives in Japan while his father and mother, Wakamatsu and Haru, immigrated to Hawai‘i prior to 1892. Though Wakamatsu was primarily a fisherman by trade, he had also farmed a small plot adjacent to his home. With farming in mind, he responded to an advertisement in a Japanese newspaper that sought workers for the pineapple and sugar beet fields of Hawai‘i. Since the prospects in Japan were limited (he was not a first-born son), Wakamatsu and his wife, like many others, went to Hawai‘i to work in the fields.

During that time, they had two additional children before Wakamatsu sent the children and their mother back to Japan. The backbreaking work in Hawai‘i did not offer a better future for his family, so he decided to seek his fortune on the western coast of the United States. He went first to Seattle, but later, in 1905, he decided to go south to Los Angeles where the climate was closer to that of his birthplace, Hiroshima.

Wakamatsu found success operating two farms in Southern California, the first in present day Maywood, and a second farm in Laguna, in what is now the City of Commerce. Immigrants, Issei like Wakamatsu, and later Wakaji, “were almost exclusively drawn from the agricultural classes of Japan,” and they naturally sought to employ their farming skills in their newly adopted land.1

Farms were labor-intensive operations, and children were expected to contribute. Sons like Wakaji often became Yobiyose, who were summoned from Japan to provide help for their fathers in the United States, which contributed to the rapid growth of Japanese immigration.2 California saw a four-fold increase in its Japanese immigrant population in the first decade of the century, culminating in a population of 41,356 in 1910 according to one source (and as high as 72,156 by another source).3 In Little Tokyo, the Japanese population surged to 20,000 by 1920, and to 37,000 by 1940.4 A California government document from 1920 indicated that “the Japanese were regarded as very valuable immigrants and efforts were made to entice them to come,” though such a welcoming attitude would change with time.5

Economic conditions in Japan were particularly difficult at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. Taxes progressively increased to cover the costs associated with the Meiji Restoration, and a disproportionally heavy load was borne by farmers. Japan’s population increased in the last part of the nineteenth century, resulting in fewer resources to support a larger population. Living conditions worsened following the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, and some young men emigrated to avoid military conscription.6 Moreover, these immigrants were ambitious and industrious, and many had dreams of flourishing in their new land before returning to Japan, years later, as successful retirees.7

In spite of their high hopes, the reality during those early years was harsh, filled with political, economic, and social obstacles, including pervasive discrimination. Alien Land Laws, for example, prevented the Japanese from owning their own farms or even leasing them for more than three years. Some got around this by buying land in the names of their American-born children, who were US citizens by birth. This was later curtailed by further anti-Asian legislation.8

Most Japanese immigrants, including their wives and children, worked as field hands doing backbreaking work in agriculture. They were often little more than human machines, as writer Carey McWilliams suggests by aptly entitling one his books, Factories in the Fields.9 The crops often required endless hours of “squat work.” Nevertheless, with surprising rapidity some of these workers graduated to tenant truck farming, often cultivating small plots of land similar in size to those of their family’s rice farms in Japan.

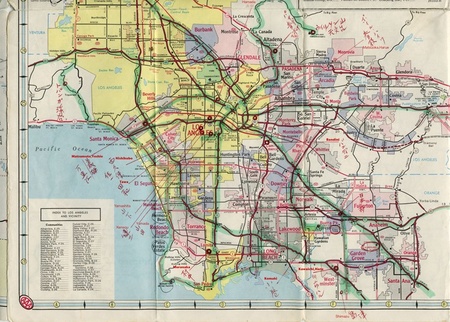

Los Angeles

In Southern California, Japanese Americans farmed at the edges of an expanding urban environment. In the early part of the twentieth century, a number of farms were situated near downtown Los Angeles in areas that are now densely populated (Fig. 1). Others were located in areas that supported farming for a longer period, but eventually became residential suburban neighbors, such as the outskirts of Fullerton, Altadena, or Buena Park.

Since they did not own the land, the Japanese seldom planted trees or grape vines that might take years to fully develop. Generally, the crops planted by Japanese Americans consisted of flowers (particularly in Northern California) and fruits and vegetables, such as celery, potatoes, onions, turnips, lettuce, and cabbage—produce that could yield a quick harvest. Gardena, for example, became known as a center for strawberry production in Southern California. In 1906, the Japanese American farmers in that area organized an association to share new techniques, labor, and equipment, and by 1910 “produced the highest value per acre of all crops in the Los Angeles area.”10

A part of their success came from their willingness to work together in cooperatives, reflecting the Japanese culture of teamwork. Some pooled their resources and partnered on leases, which helped many transition to tenant farming. Others formed organizations that distributed the farm labor, collected payments for the landowners, and paid the workers, both Japanese and non-Japanese. This arrangement was convenient for the landowners, and it allowed some Japanese to become farm operators, even though they did not own the land.

In 1900, there were only thirty-seven Japanese run farms in California. Only ten years later, 1,816 Issei farmers were at work in California. By 1941, Japanese immigrants, and the Nisei who followed, were so successful that they produced “between thirty and thirty-five percent of all commercial truck crops grown in California.”11

This was accomplished in spite of constant racism and fear. In 1921, a skeleton brief was filed with the Secretary of State of the United States by the Japanese Exclusion League of California in an attempt restrain the success of the Japanese American farmers and end Japanese immigration. Today, from a different perspective, some of the brief may be read as unintentional praise rather than racist accusation:

The Japanese possess superior advantages in economic competition, partly because of…thrift, industry, low standards of living, willingness to work long hours without expensive pleasures…women laboring as men…[combined with] extra-ordinary cooperation and solidarity…

—Japanese Exclusion League of California12

Wakaji and Tei

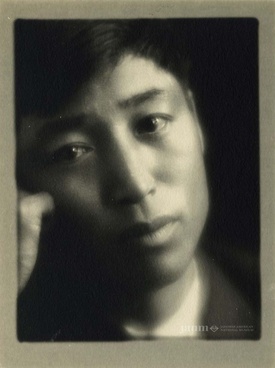

When Wakaji arrived at his father’s farm in 1906, circumstances forced him to contribute as best he could, working in the fields and driving horse-drawn wagons filled with produce to the market in Los Angeles. But Wakaji was studious and artistic by nature, and his intention was to pursue interests beyond farming. He wanted to be an artist, particularly a graphic artist, but undertaking such an endeavor in a foreign world was no easy undertaking. He began by working as a houseboy so that could he learn English. Surprisingly, it was Wakaji’s picture bride, Tei, who took over the farm operation, relieving Wakaji of obligations that might have curtailed his larger ambitions.

Tei Kimura arrived in San Francisco in 1912, coming from the same village as Wakaji. The prospective groom in the United States typically knew the would-be bride only from a photograph, thus the term “picture bride,” though there were often family or village connections. In this case, Tei’s older brother had been a classmate of Wakaji’s, and Tei knew Wakaji’s brother Yoshio since elementary school.

Traditionally, marriages in Japan were arranged by a go-between. The bride’s name was recorded in the husband’s family registry, making the marriage official in Japan. But such marriages were not considered legitimate by the US government, so mass weddings were often held at the docks or in hotels as soon as the picture brides arrived in the United States. This was not the case for Wakaji and Tei, however. When she first arrived, Tei was quarantined at Angel Island due to health concerns. Being held in detention caused her great distress, so Wakaji visited her through the fence in an effort to comfort her, but it had the opposite effect of making her feel even more the prisoner. Finally, when she was discharged, they quickly married in a church.

Tei came from a samurai family and likely had never worked on a farm. Her father was a highly regarded kendo expert and a teacher to Lord Asano of Hiroshima. Once, later in Japan, when her mother-in-law was having difficulty with a persistent drunk annoying her for money, Tei said to him, “I’m Kimura’s daughter.” He turned and ran away! Earlier, as a teenager, she was sent to live with a diplomat’s family in Korea to learn manners. But, in Los Angeles, she found herself in a very different world, that of a Japanese farming immigrant.

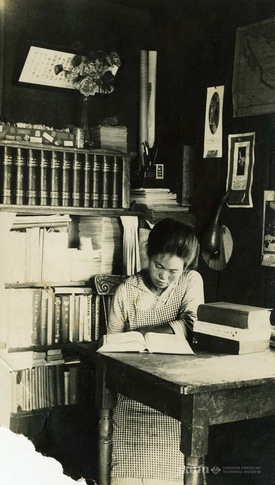

It was Wakaji’s father, Wakamatsu, who took Tei under his wing and taught her how to manage the farm and pay laborers, both Japanese American and Mexican American (Fig. 2). Tei often awoke at 2 a.m. or 3 a.m. and toiled until late at night, working the farm while caring for her growing family. She cleaned house and cooked for her family and the workers. She learned some Spanish, and even made tortillas for the Mexican American hands. Most importantly, she made a success of it. So much so, that in 1917, Wakaji’s father, Wakamatsu, left the farm in her hands, returning to Japan to join his wife in Jigozen, the small town south of Hiroshima where he had left her and their children twelve years earlier.

Notes:

1. Yamato Ichihashi, Japanese Immigration: Its Status in California (San Francisco, 1915), 22; H. A. Millis, The Japanese Problem in the United States (New York, 1915), 103.

2. Wakaji was not the first-born son, but he was the oldest surviving son, his elder brother having died in 1902.

3. Cecilia M. Tsu, “Sex, Lies, and Agriculture: Reconstructing Japanese Immigrant Gender Relations in Rural California, 1900–1913.” Pacific Historical Review 78, no. 2 (2009): 174 / Carey McWilliams, Factories in the Field: The Story of Migratory Farm Labor in California (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1935, 1939, 1966), 105.

4. U.S. Census as cited in John Modell, The Economics and Politics of Racial Accommodation: The Japanese in Los Angeles, 1900–1942 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977), 18.

5. Carey McWilliams, Factories in the Field: The Story of Migratory Farm Labor in California (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1935, 1939, 1966), 105.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid., 25.

8. Cherstin Lyon, “Alien land laws,” Densho Encyclopedia (accessed 2/11/2020).

9. Carey McWilliams, Factories in the Filed: The Story of Migrant Farm Labor in California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1935).

10. Donna Graves, “Transforming a Hostile Environment: Japanese Immigrant Farmers in Metropolitan California,” 202.

11. Ibid., 25–29. Some sources, such as A. V. Krebs, “Bitter Harvest,” The Washington Post, February 2, 1992, indicates the output was as large as 40%.

12. Japanese Exclusion League of California, Japanese Immigration and Colonization: Skeleton Brief Filed with the Secretary of State (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1921), 14.

* * * * *

This essay was written in conjunction with the Japanese American National Museum’s online exhibition, Wakaji Matsumoto—An Artist in Two Worlds: Los Angeles and Hiroshima, 1917–1944, which highlights Wakaji’s rare photographs of the Japanese American community in Los Angeles prior to World War II and urban life in Hiroshima prior to the 1945 atomic bombing of the city, and artistic photographs of daily life in both cities that were created as a form of personal expression.

View the online exhibition at janm.org/wakaji-matsumoto.

*All photos by Wakaji Matsumoto (copyright Matsumoto Family)

© 2022 Dennis Reed