One of the most prolific, and possibly most underappreciated, Asian American actors of the “Golden Age of Hollywood” was Tetsu Komai, who distinguished himself by playing villainous “Asiatics” (mostly Chinese) for the delectation of American audiences. He acted in over 60 features in the prewar decades, appearing opposite such great names as Humphrey Bogart, Ronald Colman, and Bette Davis, as well as Anna May Wong.

Tetsuo Komai was born 23 April 1894 in Kumamoto, Japan. His father was Takekuma Komai, a native of Seoul, where the young Tetsuo grew up (he never publicly claimed Korean ethnicity but his place of origin and his 6-foot height suggest that he may have had Korean ancestors).

He arrived in USA in 1916 on the S.S. Mexico Maru, entering as a student. He later claimed to have come to America to complete a civil engineering course he had begun at Kumamoto, with the idea of putting himself through school and then assisting his younger brothers to obtain an education afterwards.

Whatever the case, he settled in Seattle. In 1917, he was employed as a porter at the Georgian Hotel. By 1920 he was listed as working as an auto mechanic at the Alki Tire Company. He eventually invested in his own tire vulcanizing business.

During these years, he became friendly with a group of young Japanese immigrants in Seattle. Eventually, members of the group recruited him to play the offstage voice of the Great God Jehovah in a biblical drama written by a University of Washington professor, and translated into Japanese. Entranced by acting, Komai moved to Hollywood in the mid-1920s.

He later related that, as the tire business went from bad to worse, “I quit and beat it down here to Hollywood. I become movie actor at once…First I worry what my old man and my old gran’ma in Japan say. In Japan way back then it was not polite to be actor. But they like it fine so everything is okay.”

In February 1925, by which time Komai was already in Los Angeles, he married Yukino Furuya, eight years his junior. Their first child, Leo Gen, was born nine months later, just before the new year 1926. Two daughters, Pola Fusako and Sylvia Kyo, followed in the next years. The family at first lived near downtown, then moved to the growing Japanese colony of Gardena.

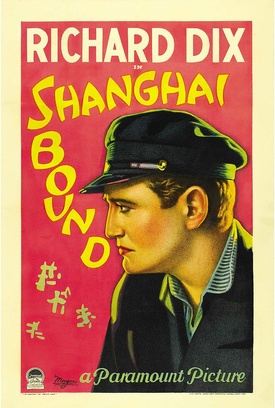

While one source states that Komai’s first recorded film role was in the silent picture The Unchastened Woman (1925), his first role of note was in the 1927 silent Shanghai Bound, starring Richard Dix. In the film, Komai portrayed the maniacal “Scarface,” the commander of rebellious Chinese bandits (or perhaps communists), who follow white travelers down the shores of China in sampans and intercept them at narrows to attack them. A publicity release stated that, as a past traveler in China, Komai was able to give the directors useful advice in dramatizing the Chinese river boat scenes.

Komai’s next important role was in the 1928 Paramount feature Moran of the Marines, also starring Richard Dix, in which Komai played the Chinese revolutionary warlord Sun Yat (not Sen). In the words of the Boston Globe’s reviewer, Komai fit the part well, as he “makes a most villainous-looking bandit.”

That same year, he portrayed a groom in the movie Woman from Moscow, starring Pola Negri, and appeared as the Chinese Chin Lee in Detectives, opposite Karl Dane.

As sound film came to Hollywood, Komai was able to adjust and flourish—his voice augmented his screen image. His first speaking role was as Won Chung in the part-talkie Chinatown Nights (AKA Tong War), starring Wallace Beery as the Irish-American leader of a gang of Chinese thugs in an unnamed Chinatown.

A critic in the Hollywood Reporter was savage over the film’s racist view of Chinese Americans: “the picture is a libel on a harmless group of laundrymen and restaurant waiters. As a contemporary picture of any Chinatown on the North American continent—and there’s none actually tougher than that in Montreal—this is somewhat antiquated.”

A larger and more positive role was offered Komai in the 1929 sound film Bulldog Drummond, screen star Ronald Colman’s first talking picture.

In the following years, as the sound era dawned, Komai became typecast as an “oriental” villain. For example, he had a supporting role in the film East Is West, a chestnut about interracial marriage. That film starred actress Lupe Velez in yellowface as Ming Toy, a tragic Chinese damsel in love with a white American youth, played by Lew Ayres. Komai played Ming Toy’s evil stepfather Hop Toy.

Soo after, Komi appeared in the classic orientalist film Daughter of the Dragon, which starred Anna May Wong as the daughter of Werner Oland’s diabolical “oriental” Fu Manchu. Komai appeared as Lao, a henchman.

Though Komai flitted through a series of minor parts during these years, he did appear in a large role in the 1932 film War Correspondent, as the villainous Chinese bandit chief General Fang. The Philadelphia Inquirer singled him out for his performance: “With his shifty eyes, his dribbling mouth, and his bulky little hunchbacked body he makes [other film villains appear in comparison] as nice amiable gentlemen. Whatever color and distinction the present film has to offer is entirely due to Mr. Komai’s sinister and expert work.” Similarly, a reviewer in TIME lauded Komai’s performance as rising above the sentimental material.

However, when later that same year he played the title role in the independent feature The Secrets of Wu Sin, set in Chinatown, he received mixed reviews. A critic in the British periodical Daily Film Renter praised Komai as “all that can be wished for as the oily rogue, Wu Sin.” However, a rather bigoted reviewer in the Hollywood Reporter charged that “Whoever played the part of the villainous Chinese… sounded like a pansy and acted like a cigar-store Indian.”

During the same period, Komai played one of his most intriguing roles, as a half-human, half-dog monster in The Island of Lost Souls. He also took the role of a savage jungle chieftain in Cecil B. DeMille’s Four Frightened People, for which he spent several months filming on location in the Hawaiian Islands.

During 1933, amid the depths of the Great Depression, Komai remained heavily in demand in Hollywood. He appeared together with Otto Yamaoka, another Japanese American screen actor, in I Cover the Waterfront, which told the story of a newspaper reporter's experiences along the San Diego waterfront.

Komai had several dramatic scenes in the film as an Asian doctor who treats an injured smuggler. That year, in the Sherlock Holmes feature A Study in Scarlet, featuring Reginald Owen, he played Ah Yet, the manservant of Mrs. Pyke (Anna May Wong). He had no lines but his presence filled a large role in the plot.

In 1934 Komai was absent from Hollywood for a time, as he returned to Korea to care for his ailing father. According to sources at the time, he declined a role in the Greta Garbo vehicle The Painted Veil. He did play a straight role, that of Mr. Ling, in Paramount’s Now and Forever, starring Gary Cooper, Sylvia Sidney, and Shirley Temple.

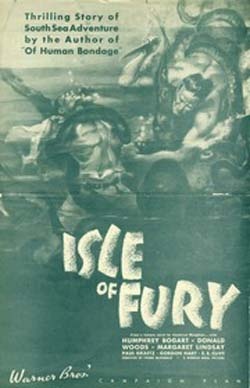

Upon his return from Asia, Komai resumed his acting career by appearing in a series of well-regarded pictures. First, he played a Chinese merchant businessman in the comedy Oil for the Lamps of China (1935), which featured a large cast of Asian actors. He then played the part of Humphrey Bogart's killer aide in Isle of Fury, adapted from a story by Somerset Maugham. He also appeared in a bit part in the 1936 Mae West comedy Klondike Annie.

While many Nikkei actors experienced a dearth of roles after 1937, as Tokyo’s invasion of China resulted in the spread of anti-Japanese public sentiment in the United States, Komai retained an active screen presence. Despite his clearly Japanese name, he may have been sufficiently associated with Chinese parts to escape blacklisting. Perhaps his talent and his willingness to play villains, ironically, protected him from criticism over his presence. Interestingly, in 1937 he was featured in a pair of movies where he was assigned more positive characterizations.

In West of Shanghai, Komai played General Ma, a Chinese military chief who conquers the evil leader of a group of Chinese bandits (played by Boris Karloff in yellowface). it was one of the few clearly heroic roles Komai was given to play. In the film China Passage, released the same year, he portrayed Wong, a Chinese investigating the theft of a diamond, who is shot under mysterious circumstances.

In the last years before World War II, Komai was able to play some more complex bad guys. In The Real Glory, starring Gary Cooper, he portrays Alipang, the leader of the Moros, a tribe of Philippine Muslims in the hills and jungles of the Sulu Kingdom who engage in guerilla warfare against the Philippine army and their American trainers. Nisei journalist James Hamada, writing in Nippu Jiji, commented “Tetsu Komai, although not sympathetically cast, has his largest role in recent years and he makes an effective Moro chief.”

The following year, he had a notable part as a malevolent chief houseboy in the Bette Davis vehicle The Letter, also based on a Somerset Maugham tale. (At least here Komai’s character, unlike so many of the film “heavies” he played, did not get killed). His last prewar role was in the Gene Tierney movie Sundown (1941), set in South Africa, where he performed in blackface as a Shenzi warrior.

Komai’s career seems not to have been immediately affected by the outbreak of the Pacific War. In his draft card, filed in April 1942, he listed his employer as the Walter Wanger production team at the Samuel Goldwyn studios, which suggests that he was then involved in a project there.

Soon after, however, he and his family were removed under Executive Order 9066. Their first confinement was at the Tulare Assembly Center. While at Tulare, Komai endeared himself to the community by organizing and directing a “patriotic” talent show for a reported audience of 400 people. Komai himself wowed the crowd by performing a skit as an outlandish infant (on the model of Fanny Brice’s Baby Snooks). Later in 1942, the Komai family was moved to confinement at the Gila River camp in Arizona.

In September 1945, the Komai family left Arizona and returned to Gardena (Son Leo initially resettled in Chicago, but by 1950 he was living back home with the family). Komai attempted to resume his work in Hollywood. However, by now he was in his mid-fifties and no longer as attractive to studios. His wife and daughters took work in an underwear factory to help support the family.

Ultimately Komai did win a handful of small parts, in films such as Task Force (1949), as a Japanese Ambassador; Tokyo Joe (1949), where he played the villainous Lt. Gen. 'The Butcher' Takenobu; a servant in Japanese War Bride (1952); and the role of a Japanese father in Tokyo after Dark (1959). Unlike in the prewar years, when he had specialized in Chinese parts, his postwar roles were actually as Japanese (other than as a Mongolian in the independent film State Department File 649).

His final screen performance was as a gardener in the 1964 film, The Night Walker. He also found work on television, most notably in a pair of episodes of the tv anthology series Alfred Hitchcock Presents: In the episodes “The Canary Sedan” (1958) and “Specialty of the House” (1959).

Tetsu Komai died 20 August 1970 of congestive heart failure in Gardena, California. His passing was not marked in the Japanese American or mainstream press. Even if his star has faded, Komai deserves to be honored as a Hollywood film pioneer.

© 2022 Greg Robinson