Taro Otsuka was born in 1868 in Kochi, Japan and rumored to be an activist and a comrade of Taisuke Itagaki, a liberal politician who advocated for liberty and civil rights in the 1880s in Japan.1 At age 30, he arrived in Seattle on December 21, 18972, leaving his wife in Japan. He listed his profession as “mineral works” and his contact in the U.S. as “T. Kataoka” in Tacoma, Washington.3

This “T. Kataoka” was Tsunejiro Kataoka from Kochi, who had come to Seattle in 1888 to help with a land clearing project that had been initiated by a man named Yonejiro Ito.4 Ito sent Katsumi Hirota, another native of Kochi, to Japan to recruit ten “comrades” to come to work with him. Tsunejiro Kataoka, the younger brother of Kenkichi Kataoka, a former speaker of the Lower House in the Japanese Diet, was one of those “comrades.” Unfortunately, the project saw no progress and soon ended,5 so Tsunejiro Kataoka moved to Tacoma to start a store named Tokio Bazaar with his brother, Shigesaburo.6 The 1899 Tacoma City Directory recorded Tsunejiro Kataoka as a furniture manufacturer as well as the proprietor of the Tokio Bazaar.

We know little about Otsuka’s life, but the various jobs he engaged tells the story of his struggle to survive. According to a description in the passenger manifest of the S.S.Riojun Maru, which arrived in Seattle on July 6, 1900, after securing employment as a clerk, possibly at the Tokio Bazaar, Otsuka went back to Japan and returned to Tacoma with his wife, Yoneko, in July 1900.

The 1901 Tacoma City Directory recorded Taro Otsuka as an interpreter and proprietor of the Popular Restaurant, while Yoneko listed as a dressmaker. In February 1904, Otsuka went to Montana as a local representative of the Oriental Trading Company, which was based in Seattle and run by C. F. Takahashi and A. T. Okamoto.7

No one is sure what then brought Otsuka to the Midwest and Chicago. However, garden historian Beth Cody thinks that it was possible that Otsuka visited the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, held from April to December 1904 in St. Louis, Missouri, to look for business opportunities. Cody believes that Otsuka must have seen how popular Japanese gardens were at the Fair:

“Otsuka was likely influenced by the design features of the Japanese gardens at the Fair, such as the heavy use of porous rocks there” which “became a feature of many of Otsuka’s gardens, either because he liked them himself, or because American patrons admired them in those St. Louis gardens.”8

At the Fair, Otsuka may have met and been encouraged by Japanese businessmen from Chicago, such as Tomihei Maruyama, to come work in Chicago.9

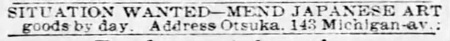

In 1904, Tomihei Maruyama and his partner, likely Usaku Kaneko,10 who he was in business with at the St. Louis Fair, founded a Japanese art goods store named Toyo & Company, at 3906 Cottage Grove Avenue, Chicago.11 It is not known exactly when Otsuka came to Chicago with his wife, but Taro Otsuka was listed in the 1906 Chicago City Directory as a tea merchant at 370 Clybourn Avenue, which means that he must have come to Chicago around 1905, after the St. Louis Fair. He probably came to Chicago as a salesman to expand the business of the Oriental Trading Company; his tea business continued until 1908.12 After he quit the tea business, Otsuka placed a “situation wanted” ad in the Chicago Tribune in February 1909: “Mend Japanese Art goods by Day. Address Otsuka 143 Michigan Ave.”13

143 Michigan Ave was the same location that Maruyama leased for Toyo & Company in 1906, as reported in the Inter Ocean: “Rounds & Wetten have negotiated [leases] … for W. J. Feeley company to the Toyo Company, the store and basement, 143 Michigan Avenue, for a term of years at a total rental of $6,000.”14 Maruyama had placed a “wanted ad” in the Chicago Tribune on May 14, 1905, looking for a “First Class Japanese Cook and Houseman, Wages $40.” It may have been Otsuka and his wife who responded to the ad and came to Chicago, doing such tasks as mending the Japanese art goods Maruyama was selling at his store.

According to the 1910 census, Otsuka was a mender of art goods,15 and possibly also worked for Toyo & Company, while Yoneko worked as a domestic in Evanston.16 In 1910, the Otsukas lived at 913 Cypress Street in Chicago with Bunkichi Shimoji, a carpenter who did bamboo craftwork.

Shimoji was 58-years-old in 1910, the oldest among the Japanese currently in Chicago.17 He had come to Chicago for the 1893 Columbian Exposition18 and had started his own business, Shimoji & Co., at 542 Ogden Avenue in 1902.19 Was it because his bamboo goods were so popular in Chicago that he moved so frequently: from Ogden Avenue to 1528 Milwaukee Avenue20, to 803 W 63rd Street21, to 5538 State Street22, and then to 1100 Paulina Street.23 Otsuka may have helped Shimoji with his bamboo goods business as well, since he had worked off and on with people engaged in the Japanese goods business since he landed in Seattle in 1897.

We can only speculate about how and why Otsuka started landscaping in the Midwest, but one source mentions that Otsuka had been a mine operator in Kochi, Japan and had become interested in rock garden work while handling stones there.24 It seems that he arrived in America with his own self-taught knowledge of landscaping. Once he had settled in Chicago, he ventured into building Japanese gardens, responding to requests from white American clients by creating ponds with rocks, hill areas representing Mt. Fuji, and adding torii, lanterns, curved bridges, and tea houses.

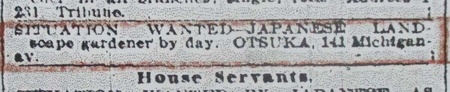

Successful businessman Milton Tootle, Jr. was his first client; Otsuka built a Japanese garden for Tootle’s summer house on Mackinac Island, Michigan around 1910.25 Encouraged by his success of this project and feeling more confident about his skills and abilities, Otsuka placed a “situation wanted” ad in the Chicago Tribune in March 1911: “Japanese Landscape Gardener By Day.”26

Soon, wealthy clients such as Frederick Bryan in Chicago and George Fabyan in Geneva began employing Otsuka. Garden historian Beth Cody speculated that: “Probably Fabyan wanted a Japanese garden and asked his gardener, an Italian man, to cast the lanterns and make a concrete pond.” But these did not satisfy Fabyan, so he called in Otsuka.27

How did Fabyan find Otsuka? One clue can be found in the business addresses Otsuka used in his ads, which matched those of Tomihei Maruyama and his Toyo & Company. Every time Toyo & Company moved, Otsuka also changed his business address in the magazine advertisements he placed to correspond.

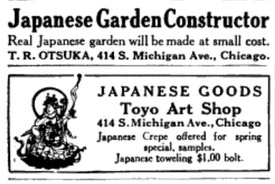

Tomihei Maruyama's Toyo & Company was so successful that he was chosen later to be President of the Chicago Japanese Association.28 He expanded his business rapidly, moving his company office and retail stores frequently, from 143 Michigan Avenue to 414 South Michigan Ave (in the Fine Arts Building),29 to 300 South Michigan Ave (in the Stratford Hotel Building),30 and later to 216 North Michigan Avenue.31

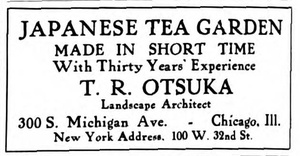

For example, after his “situation wanted” ad in 1909 listed his address as 143 Michigan Avenue, Otsuka’s advertisement as “Japanese Garden Constructor” in the February 1913 Home Beautiful magazine showed his address as 414 S Michigan Avenue, which is the same address Maruyama used from June 1911 to June 1916.32 In an advertisement in The Japan Review, a monthly magazine that Katsuji Kato of the University of Chicago started in 1919, Otsuka advertised himself as a landscape architect, listing his address as 300 S Michigan Ave.33

Furthermore, the 1917 Chicago City Directory listed Otsuka’s occupation as clerk,34 indicating that he may have worked as a clerk at one of the Toyo & Company retail stores. It would be easy to assume that out of convenience, Otsuka shared the address of Toyo & Company, and that this may have helped him find wealthy patrons through customers who were interested in Japanese art and frequented the stores of Toyo & Company.

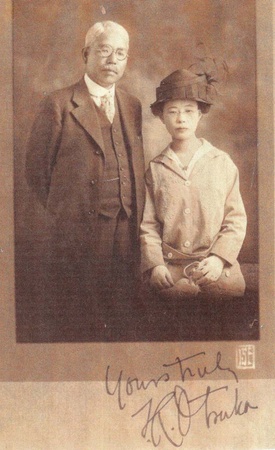

All evidence points to the fact that Maruyama and Otsuka must have been on good terms, and that their wives must have been friends as well. When the chapters of the Daughters of the American Revolution of Chicago led an Americanization drive after World War I in 1919 and opened the New American Shop, a clearinghouse for work for foreign-born citizens of Chicago, in Suite 1409 of the Stevens Building, Hisa Maruyama and Yoneko Otsuka worked together on Japanese needlework and their pictures appeared in the Chicago Tribune.35

World War I, which the U.S. entered in April 1917, made Otsuka’s life difficult as there was not enough demand for Japanese gardens for him. Otsuka started looking to expand his business in the eastern portion of the U.S., as shown in this advertisement in the September 1917 issue of Art World. In the advertisement, Otsuka promoted himself as landscape architect with thirty years of experience and listed 100 W 32nd Street as his New York address, in addition to 300 S. Michigan Avenue in Chicago.

In order to support his family, Otsuka took a job as an assistant at Reverend Shimazu’s Japanese Young Men’s Christian Institute (JYMCI) at 747 36th Street and Yoneko worked for the Chicago branch of a New York-based Japanese art goods importer, Yamanaka & Company, Inc.36 At the JYMCI, Otsuka met a Japanese man named Susumu Kobayashi, who came to Chicago from Florida looking for a job. Otsuka later helped Kobayashi find work at George Fabyan's Riverbank37 and continued to stay in touch with him even after Kobayashi returned to Florida in 1919.

Otsuka is listed in the 1920 census as a Japanese gardener, aged fifty-three, living with his wife, a saleswoman, and Naotaro Kato, an importer of Japanese goods. It is odd that Otsuka’s wife’s name was recorded as Haru, when her name was actually Yoneko.

Naotaro Kato came to Seattle in 1913 as a merchant working for a Japanese trading company in New York38 and visited Chicago in October 1916 as a traveling salesman of Japanese goods.39 He must have liked Chicago, and by 1919 he had started his own Japanese art goods business, Kato Brothers, at 208 North Wabash Ave.40 Perhaps Otsuka's wife Yoneko worked for Kato Brothers.

Notes:

1. Nichibei Jiho, June 14, 1924.

2. Washington, Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1965.

3. Washington, Passenger and Crew List 1882-1965.

4. Zaibei Nihonjin-Shi.

5. Ibid.

6. 1895, 1896 and 1897 Tacoma City Directory.

7. The Anaconda Standard, February 28, 1904.

8. Beth Cody, unpublished manuscript.

9. Ibid.

10. 1910 census.

11. The Oriental Economic Review January 10, 1911, 1905 Chicago City Directory.

12. 1909 Chicago City Directory.

13. Chicago Tribune, February 7, 1909.

14. The Inter Ocean, May 27, 1906.

15. 1910 census.

16. Evanston City Directory 1909

17. 1910 census

18. 1900 census.

19. 1903 Chicago City Directory.

20. 1905 Chicago City Directory.

21. 1906,1907 Chicago City Directories.

22. 1908 Chicago City Directory.

23. Nichibei Nenkan 1910.

24. Japanese Wikipedia for Ushinosuke Narahara.

25. Beth Cody personal correspondence, December 13, 2021.

26. Chicago Tribune, March 22, 1911.

27. Beth Cody personal correspondence, December 14, 2021.

28. Shin Sekai, December 27, 1919.

29. 1915 Chicago City Directory.

30. Chicago Tribune, July 6, 1919.

31. Chicago Tribune, August 4, 1922.

32. Beth Cody, unpublished manuscript.

33. The Japan Review, August 1920.

34. 1917 Chicago City Directory.

35. Chicago Tribune, February 27, 1919.

36. Sumiko Kobayashi’s letter to Darlene Larson, dated September 6, 1976.

37. Sumiko Kobayashi’s memoir, Susumu Kobayashi, January 1, 1976, Sumiko Kobayashi Papers, MSS71, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

38. Washington, Passenger and Crew List.

39. List of Visitors to the US Chicago Japanese YMCA, WWI registration.

40. October 1920 Chicago Telephone Directory.

© 2022 Takako Day