In the early 20th century, there was another “prominent capitalist”1 in Geneva, a town along the Fox River, forty miles west of Chicago, who enjoyed employing Japanese domestic workers at his villa. His name was George Fabyan, and, according to some accounts, was considered to be an “Honorary Japanese Consul”2 before the Japanese Consulate was established in Chicago in 1897.

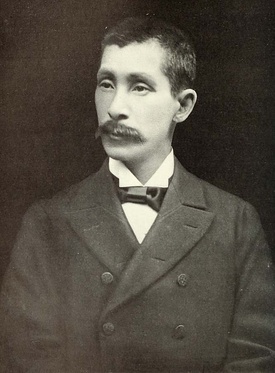

Fabyan was well-known for entertaining Japanese celebrities and was rumored to be a friend of Baron Jutaro Komura,3 and of Toshiro Fujita and Seizaburo Shimizu,4 who were Japanese consuls in Chicago, the former from 1899 to 1902, and the latter from 1903 to 1906.

George Fabyan was descended from New England Brahmins5 and was the eldest son of successful businessman George Francis Fabyan of Bliss, Fabyan & Company, one of the largest dry goods commission houses in the East. His father was a well-known supporter of Harvard University, where he established the Fabyan Endowed Professorship of Comparative Pathology in what was then the new Harvard Medical School.6 Could the upper-class social gatherings of Brahmin society and Harvard have provided occasions for George Fabyan’s first childhood contact with Japanese?

In 1875, Baron Jutaro Komura, one of the first Japanese students to be sent overseas by the Japanese government, began his studies at Harvard where he would remain for three years. After graduating, he worked at the Edwards Pierrepont law office in New York for two years.7

As one of the few Japanese students at Harvard, Komura was reputed to be very popular, and was well-accepted in Boston proper. When Dr. Alexander Graham Bell, a professor of vocal physiology and elocution at the Boston University School of Oratory, was looking for foreign language speakers to test his new invention, Bell chose Komura at Harvard and let him converse in theJapanese language for the first time on the telephone.8

We know that Fabyan was so interested in “acoustics, cryptography, genetics and physiology”9 that he built private acoustical laboratories on his property in Geneva, Illinois. While there is no definite evidence to show that his affinity for Japanese started from the time that Komura was enlisted to test the telephone, Fabyan entertained numerous celebrities in Chicago and Geneva which helps us trace the chronology of a development of a strong US-Japan relationship.

George Fabyan and Japanese Celebrities

George Fabyan came to Chicago around 1893 as the western representative of Bliss, Fabyan & Company of Boston and New York.10 He lived at 3251 Michigan Avenue in Chicago and his office at Bliss, Fabyan & Company was located at 160 West Jackson Boulevard.11 One of the earliest Japanese celebrities he entertained in Chicago was Hirobumi Ito, the famed Japanese statesman, who was making his third visit to Chicago in 1901.

Following Ito, Fabyan entertained many well-known Japanese politicians, businessmen and even members of the Imperial family, by inviting them to luncheons, dinner parties, and theater outings in Chicago. These celebrities included Japanese statesman Count Masayoshi Matsukata in April 1902,12 prominent businessman Eiichi Shibusawa, who came to Chicago for the first time in June 1902, Prince Sadanaru Fushimi who came to see the St. Louis Exposition during the Russo-Japanese War, in November and December 1904, and Jutaro Komura, peace envoy for the Russo-Japanese war, who visited in July 1905, and many others. When the train car carrying Komura stopped in Chicago, George Fabyan climbed aboard the car and welcomed him. At the station, Japanese residents of Chicago shouted “Banzai” and “made stiff little bows in the occidentalized Jap manner.”13

General Baron Tamemoto Kuroki, hero of the Russo-Japanese War, along with his entourage of high-ranking Japanese army officers, were probably the first Japanese entertained at Fabyan's Riverbank in Geneva, while they were on a tour of the U.S. First, they attended the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia, then on the way back, they traveled to Chicago on May 27, 1907. After being welcomed by the “Banzai” cries of local Japanese and Americans at the train station,14 Kuroki visited the Lincoln Monument in Lincoln Park, placed a wreath, and not only attended, but threw several banquets for prominent Chicago residents, including George Fabyan.15

Although General Kuroki and his staff had planned to attend a baseball game in Chicago, at the invitation of Fabyan, late on the morning of June 1, 1907, Kuroki arrived in Geneva instead, to attend a banquet at the Fox River Country Club, located on the southern edge of the estate that Fabyan owned.16 The club had a newly-built addition, which had been designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1907.17

At the same time, the Fabyan Villa, a farmhouse in the middle of a 600-acre tract along the Fox River,18 was also being renovated under the direction of Wright. Wright was “then a little-known architectural radical”19 but soon thereafter became a well-known architect famous for his modern “prairie” style. Fabyan lived at the Villa from around 1907 until his death in 1936.

After returning to Japan, General Kuroki sent a note to Fabyan in appreciation of his warm welcome.20 For his courteous hospitality towards these Japanese celebrities and his efforts to form a bridge between Japan and Chicago,21 George Fabyan was decorated with the emblem of the 5th Order of the Rising Sun in 1908.22

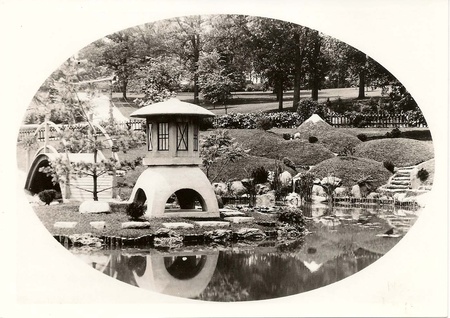

Diplomat Aimaro Sato must have met George Fabyan several times because he had accompanied both Prince Sadanaru Fushimi on his trip to Chicago in 1904 and Jutaro Komura in 1905. When Sato returned to Chicago as Japanese Ambassador to the U.S. in 1916, Fabyan invited him, along with Chicago consul Saburo Kurusu, to Riverbank and entertained them at the teahouse in the Japanese garden there.23

Japanese garden at Fabyan Villa

The tea house still stands today in the corner of the Japanese garden at Fabyan Villa, and although it has been renovated, it is nearly identical to the original one. Next to the tea house there is a small stone on which, engraved in Japanese, is the name, Fabyan, in hiragana: ふびあん. Who carved his name on the stone in Japanese? The identity of the stone carver is not known at this point, but one possible suspect is Taro Otsuka.

Taro Otsuka was a popular Japanese garden designer in the Midwest in the 1910s and 1920s. George Fabyan was one of his earliest wealthy customers and Otsuka built the Japanese garden for him around or soon after 1910.24 Besides Fabyan, among Otsuka’s industrialist/capitalist clients in Illinois were Chicago meatpacker Edward Morris of Morris & Company, Lake Forest meatpacker Louis F. Swift of Swift & Company, Joy Morton of Morton Salt Company in Lisle, and Harlow D. Higinbotham, whose father, Harlow N. was a president of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and a partner in Marshall Field & Company in Joliet.

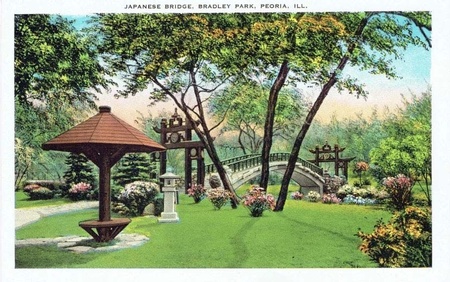

Japanese culture and art were considered extravagant during this time period, and Japanese gardens were seen as status symbols. Otsuka’s rich clients also included Arthur Hill of D. Hill Nursery Company in Dundee and Frederick W. Bryan in Chicago. He worked as designer for the Laura Bradley Park, a public park which was named after the young daughter of a wealthy woman who donated the money to establish a park in Peoria, Illinois as well. His reputation as a Japanese garden expert was well-known outside of Illinois as well, in states including Kentucky, Minnesota, Indiana, Michigan and Ohio. It seems that he would travel anywhere in the Midwest at a customer’s request, and his savvy sales pitches included the phrases “small cost”25 and “quickly constructed.”26

Notes:

1. Chicago Daily Journal, July 21, 1914.

2. Munson, Richard, George Fabyan: The Tycoon Who Broke Ciphers, Ended Wars, Manipulated Sound, Built a Levitation Machine, and Organized the Modern Research Center, page 59.

3. Chicago Tribune, July 25, 1905.

4. Twice-A Week Republican, June 1, 1907.

5. Munson, page 15.

6. Fibre and Fabric: A Record of American Textiles Industries, January 26, 1907, Annual Reports of the President and Treasurer of Harvard College.

7. Komura, Binji, Kotsuniku, page 48.

8. Hurrey, Charles, “Famous Foreign Graduates Hold a Reunion”, World Outlook, July 1917, page 9, Komura, Kotsuniku, page 137.

9. Munson, page 1.

10. Chicago Tribune, December 15, 1939.

11. 1907 City Directory.

12. Chicago Tribune, April 5 and 6, 1902.

13. Chicago Tribune, July 25, 1905.

14. Chicago Tribune, May 28, 1907.

15. Chicago Tribune, May 31 and June 1, 1907.

16. Twice-A-Week Republican, June 5, 1907.

17. Storrer, William, The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion, page 131.

18. Kane Country Chronicle, June 5, 1991.

19. Munson 25.

20. Twice-A-Week Republican, August 10, 1907.

21. Umetani, Noboru, Meiji-ki Gaikoku-jin Jyokun Shiryo Shusei, Vol 4.

22. Ibid, ChicagoTribune, May 12, 1908.

23. The Wisconsin State Journal, October 20, 1916.

24. Correspondence with Beth Cody, Fabyan garden postcard, June 1910.

25. Advertisement, House Beautiful, February 1913.

26. Advertisement, Asia, April 1923.

© 2022 Takako Day