An intriguing pendant to the life of Yoshio Kai is the story of his sister Miwa, six years his junior. Born in San Francisco in 1913, she moved to Japan with the Kai family, as mentioned. However, perhaps because of the damage done by the 1923 earthquake, Miya was desperate to leave her new Japanese home. Though she was only 11, she was able to secure her return from Japan to the United States, in the company of Mrs. Kyutaro Abiko (the wife of the editor of the Nichi Bei Shimbun).

Once settled again in San Francisco, Miwa was placed in the care of Toro Kawasaki, then a secretary with the Japanese consulate, and his white American wife Edith. Edith Kawasaki was a skilled piano teacher who had already started teaching piano to Miwa and her siblings before they left San Francisco. (Family legend has it that Mrs. Kawasaki was not a great teacher—Miwa would instead have her brother buy her a recording of any piece she had to play, so that she could practice by imitating it).

In any event, Miwa made rapid progress on the instrument, and was soon playing alongside other pupils in group recitals. Although she later maintained that she was scarcely better as a performer than her Japanese counterparts, she swiftly acquired a reputation as a child prodigy.

In September 1925, her performance was broadcast on San Francisco’s KLX radio, on a program featuring the local Japanese consul. In 1927, at the age of 14, she received the Beethoven Prize at the Piano Playing Tournament in San Francisco.

In Fall 1927, Miwa returned to Japan with the Kawasakis as part of a concert tour. While she was in Japan, she was reunited with her birth parents, who reclaimed her from the Kawasakis. Miwa was so upset by the two couples’ struggle over her that she ran away from home and was found in a park. In the end, she unwillingly joined her parents and remained in Japan. She returned to her parents’ house so suddenly that her clothes and personal belongings were left behind with Ms. Kawasaki (whom she was never to see agan) and had to be retrieved later.

Once settled back in Japan, Miwa enrolled in high school. According to some stories, her family arranged a marriage for the teenager to a Japanese nobleman, but the engagement was evidently called off.

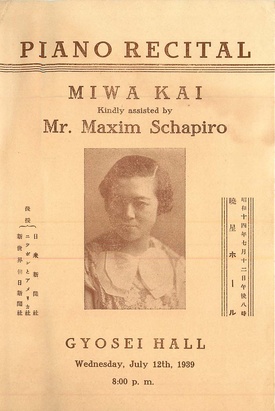

During her years in Tokyo, Miwa continued her musical training, studying with piano virtuoso Maxim Schapiro (who was also the teacher of Nisei pianist Aiko Tashiro). In 1932, Miwa earned widespread attention when she finished in first place at the all-Japan Music Contest sponsored by the Tokyo Jiji Shimpo, with a one thousand-yen prize. Three years later, she appeared as a soloist, performing in Tokyo’s Hibiya Hall under the baton of esteemed conductor Hidemaro Konoye (Prince Konoye’s brother).

In 1937, Miwa represented Japan as a participant in the quadrennial International Frederick Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw, Poland (Chieko Hara, a Japanese-born pianist then living in France, also played for Japan). In order to travel to and from Poland for the concours, Miya took the Trans-Siberian railroad. While en route, she performed with the Harbin Philharmonic in Japanese-dominated Manchuria.

Miwa caused a sensation in Warsaw. Although she did not finish among the finalists (as Chieko Hara had done), her playing and personality so impressed concertgoers that she was invited to perform before the President of Poland at a reception for the Competition participants and the diplomatic corps.

Following her triumph, the Japanese Embassy in Berlin invited her on an all-expenses paid tour of London, and she then stayed as a guest at the Japanese legations in Paris and Vienna. She returned to Japan as a popular media figure, and her renown increased soon after when she gave a recital of Chopin and other artists at Hibiya Hall, under the auspices of the Polish minister to Japan and the Nichi Nichi newspaper.

In the months that followed, Miwa gave recitals in Tokyo and Osaka. After her Tokyo concert, the Musical Courier praised her “facile technic and real art,” while the Japan Advertiser proclaimed that she “had a brilliant future.”

She meanwhile appeared several times on the Japanese radio and made a concert tour of Manchuria—playing in the cities of Dairen, Mukden, and Hsinking (today known, respectively, as Dalian, Shenyang, and Changchun). In February 1939, she performed in a two-piano recital in Tokyo with her teacher Maxim Schapiro.

In May 1939, Miwa Kai, by then age 26, returned to the United States, accompanying entertainer Takiko Mizunoe on a goodwill tour sponsored by the Japan Tourist Bureau. In June 1939, after arriving, she performed a recital at Gyosei Hall of music by Chopin, Liszt, Mendelssohn, and Rachmaninoff.

She returned to Japan soon after, but in January 1940, Miwa once more journeyed to California, this time for an announced one-year stint. She settled in San Francisco, and opened up a piano school. She continued training and performing with Maxim Schapiro.

In April 1942, while still living in San Francisco, Miwa Kai was confined by the US government at the Santa Anita assembly center. In October 1942, she was moved to the Topaz camp. While at Topaz, she taught piano in the camp Music School, alongside such colleagues as former prodigy Newton Tani, and played in faculty concerts. (While Miwa Kai was at Topaz, she was visited twice by Maxim Schapiro).

In December 1943, Miwa Kai was able to leave Topaz, and moved to Chicago to work for the anthropologist and War Relocation Authority official John Embree. During this time, in coordination with Embree, she translated Taeko Yamaji’s book, The Diary of a Japanese Innkeeper’s Daughter.

In 1944 Miwa moved to New York, where she was hired in 1945 by the Columbia University Library. At first she worked as a typist, earning just 60 cents an hour. However, because of her fluent Japanese, she was assigned to catalogue the library’s new Japanese collection (most of the materials had previously been in the collection of New York’s elite Nippon Club, which had been forced to close after Japan’s Pearl Harbor attack).

Following the end of the war, Miwa Kai spent two months at the Library of Congress helping to catalogue Japanese-language books confiscated from libraries throughout Japan and brought to the United States. In the process, she identified thousands of duplicate books, which she was permitted to add to Columbia’s collection.

In the years after World War II, as Assistant librarian and head of the Japanese collection, Miwa Kai (known universally as Miss Kai) established a formidable reputation for aiding scholars of East Asian studies. In addition, she produced her own reference works. In 1957, along with Professor Philip B. Yampolsky, she published The Political Chronology of Japan, 1885-1957. She also helped produce elementary textbooks on Japanese language such as the 1955 guide Say it in Japanese, a 124-page language training volume with recordings.

In 1983, after almost 40 years at Columbia, Miwa Kai reached the mandatory retirement age of 70, and officially stepped down from her position as librarian. Because of her great contributions, even after her official retirement she was granted the privilege of retaining office space to pursue her projects. In honor of her service, a plaque in her honor was installed in Columbia’s in the Starr East Asian Library reading room and a cherry tree planted in her honor outside the University’s Kent Hall.

Even in her retirement years, she continued to go to her office almost every day and to be active in aiding scholars. She likewise served as bibliographic assistant to the University Committee on Asia and the Middle East.

In 1995 Miwa Kai was awarded the Fourth Order of the Precious Crown, Wisteria, by Emperor Akihito at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, for her work in promoting Japan Cultural Exchange and contributing to general understanding of Japan.

Meanwhile, she continued her own scholarly activity. In 1984 her wartime translation of the book The Diary of a Japanese Innkeeper’s Daughter was at last published by Cornell University. She also produced The David Eugene Smith Collection of Works in Japanese on Japanese Mathematics in 1986 and Japanese Woodblock Printed Books and other Unique Japanese Materials at Columbia University (2 volumes in 4 parts) in 1996.

In her last years, she undertook a large-scale history of the East Asian collection at Columbia University, but did not complete it before she died, at age 98, on December 10, 2011.

© 2022 Greg Robinson