Throughout Japanese American history, a number of individuals have mobilized in response to incidents of racism facing their community. Along with calling for the end of anti-Japanese discrimination, a smaller number of Japanese American activists, of whom Yuri Kochiyama is perhaps the most prominent, have willingly connected their own experiences to broader issues of civil rights, by joining forces with African Americans. Several of these individuals have found their advocacy inspired by their spiritual duty to advocate for equal treatment of all races. Reverend Kyoshiro Tokunaga described the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans as part of “America’s karma,” and several Christian ministers, such as Reverend Lloyd Wake of San Francisco, used their spirituality to fight for civil rights.

One notable example of a spiritual supporter of civil rights was Reverend Daisuke Kitagawa. An Episcopal priest who faced wartime incarceration at Tule Lake concentration camp, Reverend Kitagawa framed the incarceration of Japanese Americans as part of a broader struggle against white racism in the United States, and pursued a long career as an advocate for several groups, such as Native Americans and African Americans. Known by many as “Father Dai,” Reverend Kitagawa served as an important catalyst for the growth of the Japanese American community in Minneapolis.

Daisuke Kitagawa was born in Taihoku City, Japan (now known as Taipei, Taiwan) on October 23, 1910, the oldest son of Reverend Chiyokichi Kitagawa, a missionary affiliated with the Anglican Church in Japan. Daisuke and his brother Joseph would both followed their father’s calling and become Anglican priests. (Joseph Kitagawa will be the subject of a future article).

In 1928, Kitagawa enrolled in St. Paul/Rikkyo University, one of Japan’s leading schools of theology. One of his instructors, the Bishop of Kyoto Shirley H. Nichols, mentored Kitagawa. After completing additional training at Central Theological College in Tokyo, Daisuke Kitagawa began work as a minister, spending four years in the city of Fukui, Japan.

In 1937, Kitagawa decided to continue his education at the General Theological Seminary in New York. With his steerage passage to the United States and visa paid for by Dean Hughell Fosbroke of the Seminary, Kitagawa arrived in New York in August 1937.

Although Kitagawa focused on his theological studies in the period that followed, he occasionally connected with the Japanese communities of New York City. He recalled in his memoirs that, after giving a half-hour sermon in eloquent Japanese, he suddenly realized that none of the Japanese American parishioners present could understand the sermon.

After two years of training, Kitagawa graduated from the seminary. On June 16, 1939, the Episcopal Church officially ordained Kitagawa as a deacon. The New York Times reported on his ordination, which took place at the Church Mission House at 281 Fourth Avenue.

In September 1939, Kitagawa received his first assignment as a resident minister of St. Paul’s Church in Kent, Washington. As minister to the Japanese communities of the White River Valley, Kitagawa worked hard to build up his parish amid the staunchly Buddhist majority of the community. As part of his duties, he assisted the Japanese minister of St. Peter’s Church in Seattle, serving as head of the church’s youth program.

On Sunday, December 7, 1941, Kitagawa led an early morning service at St. Paul’s Church. In addition to his normal sermon, he later recorded, Kitagawa added a prayer in the names of President Franklin Roosevelt, Secretary of State Cordell Hull (in his memoirs, he mistakenly referred to the Secretary of State as Henry Stimson), and the Japanese envoys sent to D.C., in the hope that a peace settlement could be achieved.

After dinner that evening, Reverend Kitagawa learned of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Immediately, he went to work helping the fear-stricken community. He met with families who had relatives detained by the FBI during the mass arrests of community leaders. He volunteered his services to the FBI as an interpreter for the interrogation of arrested Issei men.

One night, as Kitagawa was returning home after consoling various families, his car was hit by a drunk driver. As he searched for a phone to report the incident to the local sheriff’s office, an Army officer appeared. The officer interrogated Kitagawa, then took him into custody. When Kitagawa told the officer he had left the lights on at home by accident, the officer responded, “I doubt very much that the planes of your country will come this far.” The next day, after learning from the residents of Kent of Kitagawa’s upstanding reputation as a Christian minister, the officer informed Kitagawa that he was releasing him.

When news of the evacuation order arrived at Kent, Reverend Kitagawa closed St. Paul’s Church and prepared to join his congregation in camp. He noted in his memoirs that even though select Christian leaders protested the forced removal policy in the press and before Congress, he felt disappointed by the lack of organized action taken by Christian groups to oppose the incarceration.

On May 10, 1942, Reverend Kitagawa and other Japanese Americans departed the White River Valley by train for the Pinedale Detention Center near Fresno. While at Pinedale, Kitagawa continued to lead services for Christians incarcerated there.

Kitagawa later recalled that he preached his best sermons while at Pinedale, and noted that services were well attended as inmates became more religious during their confinement. On July 4, Kitagawa penned a special message that ran in the center’s newspaper, the Pinedale Saw Dust. Kitagawa praised the community for coming together and extolled the importance of making the best of the situation.

In September 1942, the Army closed Pinedale Detention Center and sent Kitagawa and other inmates to the Tule Lake Concentration Camp. Upon arrival, Kitagawa immediately began working on organizing Sunday school classes. He collaborated with his friends, Methodist ministers Andrew Kuroda and Shigeo Tanabe, on organizing Protestant religious activities in camp.

As Kitagawa later noted in his memoirs, life in Tule Lake proved more stable than in the detention centers but also more challenging. Kitagawa was in a unique position, as he shared a homeland and language with the immigrant generation, but was barely 30 years old, the same age as the older Nisei, and had many Nisei parishioners. Kitagawa paid particular attention to the needs of the Issei, who suffered from what he described as deteriorating morale, as forced removal and confinement had robbed their lives of a sense of purpose. At the same time, Kitagawa observed, the Nisei proved more optimistic as a result of being acclimated to life in the United States, but were similarly disoriented as a result of their incarceration.

WRA teacher Charles Palmerlee filmed a smiling Kitagawa, in the company of Reverend Shigeru Tanabe and his wife, emerging from the Tule Lake Union Church following a Sunday Mass. The film, dating from 1943, represents one of few visual sources to reveal life within Tule Lake Camp.

Kitagawa was a prominent figure at Tule Lake. The diary of one JERS staffer described Kitagawa as beloved by Issei and Nisei alike. As a bachelor, the staffer noted, Kitagawa constantly received attention from Issei mothers hoping to introduce their daughters to him.

At times, Kitagawa opposed the government on behalf of Japanese Americans. In 1943, Tule Lake was visited by staffers from the Office of War Information (OWI), who called on Kitagawa and other community leaders to record a message to Japan that confirmed that they received fair treatment. The OWI’s goal was to improve the treatment of American prisoners of war in Japanese hands. However, Kitagawa pointed out that most of the incarcerated were American citizens, while the other community leaders complained of the hardships of camp life they faced. The proposed message was ultimately cancelled.

Nonetheless, a number of recalcitrant incarcerees despised Kitagawa, and the Reverend remained in danger of violent attacks. In February 1943, Reverend Andrew Kuroda observed that Kitagawa had earned a reputation as a tool of the administration by serving as a translator for the WRA staff. One resident witnessed several attacks on Kitagawa, with disgruntled residents throwing garbage at him while calling him inu, or dog. Because of persistent threats against Kitagawa, a guard accompanied him during business hours, a practice which only heightened his reputation as pro-administration.

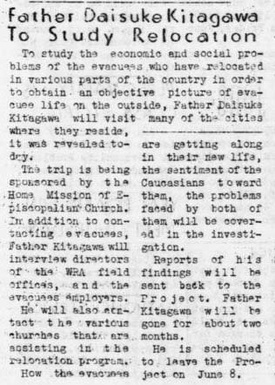

Tired of threats, Kitagawa and other ministers searched for an opportunity to escape camp. In June 1943, Kitagawa received approval from the WRA to leave Tule Lake to take a two-month tour of various cities where Japanese Americans leaving camp had resettled. His trip, which took him to Minneapolis, Chicago, Cleveland, and Kansas City, gave him the chance to meet with resettlers and see the work of religious organizations, such as the Church of the Brethren’s hostel in Chicago.

Even after he returned to Tule Lake in August 1943, Kitagawa sought an opportunity to leave permanently. Following the conversion of Tule Lake into a segregation center, Kitagawa witnessed morale deteriorate rapidly.

In September 1943, the Federal Council of Churches hired Kitagawa as field secretary for their Committee on Japanese American Resettlement, providing him a chance to leave permanently. On October 31, 1943, Reverend Kitagawa left Tule Lake for the East Coast – days before violent protests broke out and martial law engulfed the camp.

As part of his duties, Kitagawa made several trips to cities across the U.S., including Boston, Denver, New York, and Chicago. One such trip took him to the Heart Mountain concentration camp in Wyoming, where he met with Buddhist priest Reverend Gyomei Kubose on issues related to resettlement. During his tours of the Midwest, Kitagawa met Fujiko Sugimoto, a Nisei student at Heidelberg College. The two married in Chicago on July 1, 1944.

In July 1944, Reverend Kitagawa received an assignment from the Federal Council of Churches to serve as chaplain for the Military Intelligence Service’s school at Fort Snelling. Following the suggestion of Major Paul Rusch, Colonel Kai Rasmussen specifically requested Kitagawa, both because of his knowledge of Japanese culture and his ability to understand the issues plaguing Nisei soldiers who recently arrived from camp.

From July 1944 until April 1946, Kitagawa provided guidance and moral support to soldiers based at Fort Snelling. Reverend Kitagawa organized regular talks in addition to his weekly mass. One of Kitagawa’s speakers, his former mentor, Bishop Shirley Nichols, gave a presentation at Fort Snelling in part because his son was among the soldiers being trained for translation work.

In April 1945, as the West Coast reopened to Japanese Americans, Reverend Kitagawa returned to the White River Valley to investigate local attitudes regarding resettlement. In a report to the WRA, he stated that resettlers would be warmly welcomed in the area, despite the hostility of the Washington state government towards them. Kitagawa noted that many Christian leaders were helpful in encouraging locals to welcoming back their former Japanese American neighbors.

Even as he served the MIS, Kitagawa was named minister of a Japanese Christian Church in Minneapolis, He soon emerged as a leading figure in the resettlement of Japanese Americans to the Twin Cities area. Reverend Kitagawa spoke before local community organizations, schools, and churches. (One of the speakers who appeared alongside Reverend Kitagawa was then-Army Captain Spark Matsunaga, a future U.S. senator from Hawaii). Kitagawa also worked with the St. Paul Resettlement Committee to open a hostel for Japanese Americans newcomer.

In 1946, Reverend Kitagawa sponsored the creation of the Twin Cities chapter of the JACL. On June 1, 1949, Reverend Kitagawa officiated at the opening of a Minneapolis Nisei Center area at 2200 Blaisdell Avenue. The center still exists to this day. Throughout his time in Minneapolis, Reverend Kitagawa rose to prominence among the Japanese American community as an influential spiritual leader and community organizer. He also became known for officiating dozens of weddings of Fort Snelling soldiers and new resettlers in Minneapolis.

© 2022 Jonathan van Harmelen