The relationship between Japan and Russia has worsened since Russia invaded Ukraine in February this year, and the places and people associated with the history of Japan and Russia must be feeling complicated. This occurred to me while on a reporting trip along the coastline of the Hokuriku region recently.

The trip started in Niigata City and we drove along the coastline of Toyama, Ishikawa, and Fukui. On the way, we went around the Noto Peninsula and visited Rokkozaki at the tip of the peninsula. There we saw a sign that said "772 km from Vladivostok." Russia was quite close.

After this, we continue west again and soon reach the tourist spot of Tojinbo once we enter Fukui Prefecture. From here, we continue south along the Echizen Coast on National Route 305 and enter Tsuruga City. Tsuruga City is known for its nuclear facilities, including the Tsuruga Nuclear Power Plant Units 1 and 2 of the Japan Atomic Power Company, but in fact, before the war, this was the gateway from Japan to the Eurasian continent, connecting it to Europe.

More than 30 years ago, I covered a plan to build a ferry linking Tsuruga with the East Sea of Korea. The plan was pushed forward by passionate citizens who said, "We can't rely solely on nuclear power. Let's bring back Tsuruga's former glory as a port town." Unfortunately, it never came to fruition, but during the course of this coverage, I learned that many Japanese and foreigners had been traveling by rail and sea via Tsuruga.

Upon further investigation, I discovered that Tsuruga has been a hub of transportation and trade with the continent since ancient times, and also a logistics base. In 1912, an "international train" was running between Tokyo (Shinbashi) and Tsuruga's Kanagasaki Station. The train traveled west from Tokyo on the Tokaido Line, then switched to the Hokuriku Main Line at Maibara in Shiga Prefecture and reached Tsuruga. From Tsuruga, I changed to a boat and went to Vladivostok in Russia, and from there it was a magnificent route that continued to Europe via the connected Trans-Siberian Railway.

In 1927, the route was extended to London, and the flight arrived in London exactly 15 days after leaving Tokyo. When I saw a photo reproduction of the ticket from that time, which said "Tokyo-Berlin" via Khabarovsk and Warsaw, I couldn't believe it at first. Many Japanese people departed for the continent from Tsuruga.

A spirited song called "The Great Tsuruga March" was also born.

Shall we go east or west? Tsuruga is an oriental wharf. If we linger, the tape will get wet. Tomorrow, under the stars of a foreign land

Just as people departed from Yokohama and Kobe on the Pacific coast and traveled to foreign countries such as North and South America, a similar flow of people had been taking place on the Sea of Japan coast via regular shipping routes since before the war.

In contrast to the Japanese who left, Europeans arrived at the port of Tsuruga. As a stopover on the railway, Tsuruga became bustling, welcoming foreigners. Similarly, many Japanese settled in Vladivostok as a hub for people and goods, and a Japanese community, or "Japanese town," was born.

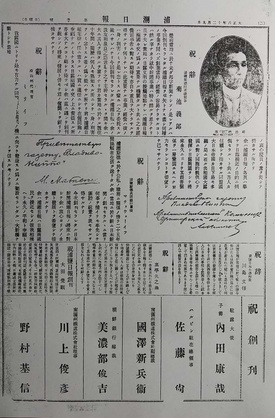

I learned about this at a library in Tsuruga. The library had a copy of the Urashio Nippo, a Japanese newspaper published in Vladivostok before the war. The thing Japanese people who go abroad want most is information. When a community is formed, it is only natural that a Japanese newspaper would be born.

Visiting Tsuruga for the first time in over 30 years, I explored the connections between Japanese people in Vladivostok and Tsuruga, including the Urashio Daily News.

The Urashio Nippo is still kept in the Tsuruga City Library, but I was able to view the paper on a DVD copy. The first issue was dated December 9, 1917. It states, "Publisher/editor/printer? (illegible) Izumi Ryonosuke," "Publisher: Urashio Nippo Company, No. 8, Seminovskaya Street, Urashio-Shitoku City, Russia, Tel. 284," and "Branch office: Ueda Teiju, Oshima-cho, Tsuruga Port," which shows the magazine's close relationship with Tsuruga.

On the bottom of the front page, next to the words "Congratulations on the founding" are the names of "Count Terauchi Masaki, President of the Japan-Russia Association," and "Baron Goto Shinpei, Vice President of the Japan-Russia Association."

5,000 Japanese in Vladivostok

Tsuruga Port was once home to the "Tsuruga Port Station," where the Europe-Asia International Train arrived and departed. In 1999, in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the port's opening, the city of Tsuruga recreated the "Old Tsuruga Port Station" and opened it as the "Tsuruga Railway Museum."

Inside the museum, there was a large-scale display of the "Europe-Asia International Express Train Timetable." According to the timetable for the "Japan-Moscow-Berlin-London-Paris Express," trains that departed from Tokyo passed through Maibara and Tsuruga, then Vladivostok and Moscow, and then Warsaw or Riga (the capital of Latvia) on their way to Berlin, London, or Paris.

This international train service was temporarily suspended during the Russian Revolution, but resumed in 1927. Trains connecting with international shipping routes seem to have continued to operate until the start of the Pacific War.

Through this flow of people, Vladivostok became familiar to Japanese people. So, what kind of Japanese community was formed and how? When I returned from my trip and looked into it, I found several studies by experts.

One of these books, "Vladivostok: A History of Japanese Residents, 1860-1937" (by Zoya Morgun, translated by Fujimoto Kazuo, Tokyodo Publishing, 2016), provides a comprehensive record of the activities of Japanese people from their arrival in Vladivostok in the early 1860s until 1937, when all Japanese residents except for consulate general staff were expelled.

Looking at events related to Japan in chronological order, a Japanese trade official was appointed to Vladivostok in 1876. A regular shipping route between Vladivostok and Nagasaki was opened in 1881, Nishi Honganji Temple began missionary work in Vladivostok in 1886, and a Japanese resident organization was organized in 1892. The number of Japanese residents in 1917 was estimated at approximately 5,000.

Later, as a result of the Russian Revolution and Japan's Siberian Intervention, many Japanese withdrew in 1922, but many remained and continued to be active.

During their long years of residence, Japanese schools were established, various shops were established, artisans gathered, and entertainment venues were formed. In this book, there are also photographs of Japanese women walking around town in kimonos.

Ultimately, as a result of the Anti-Comintern Pact signed in 1936, the Japanese were expelled the following year. There are still traces of Japanese residents in Vladivostok, and I imagine there may be some people of Japanese descent there. At the end of my trip to Hokuriku, I visited Takahama Town in Fukui Prefecture, and a man working at the hotel where I was staying told me, "My grandmother was in Vladivostok, too."

Russia will likely remain a distant country for some time to come, but I would like to visit and follow the footsteps of Japanese people in Vladivostok someday.

Read "Part 9: Continued: Vladivostok, the Footsteps of Japanese People" >>

© 2022 Ryusuke Kawai