This month, we are happy to present two poems from San Francisco-based writer and visual artist, Shizue Siegel. As the founder/director of Write Now!, Shizue amplifies many voices throughout the Bay Area, and here we are honored to share her voice with pieces about her Baachan. Through this writing, we are treated to her history and endeared cultural context, the many layers of compassion from and for a grandmother, the images of Shizue's childhood and the resilience of her Baachan's love and strength...enjoy.

—traci kato-kiriyama

* * * * *

Shizue Seigel is a Sansei writer and visual artist based in San Francisco. Her family was displaced by incarceration from Pismo Beach and Stockton, California, and she grew up an Army brat in segregated Baltimore, Occupied Japan, California skid rows and sharecropping camps. She is a Jefferson Award winner, three-time San Francisco Arts Commission Artist Grant recipient, and a VONA/Voices fellow. Her seven books include In Good Conscience: Supporting Japanese Americans during the Internment, My First Hundred Years: The Memoirs of Nellie Nakamura, and four anthologies of Bay Area writers and artists of color. Her prose and poetry have been published in We’ve Been Too Patient, All the Women in My Family Sing, Your Golden Sun Still Shines, InvAsian, Cheers to Muses, Empty Shoes, Away Journal, Eleven Eleven, Persimmon Tree, Lunchbox Moments, and elsewhere.

Baachan’s House

*Dedicated to my Stockton baachan, Shige Matsumoto Saiki

My baachan—Japanese for “grandma”—runs a hotel south of the canal.

It’s a cheap SRO in the middle of the block between the pool hall

and the Jesus mission where the open door reveals

rows of stoic men slumped in folding chairs pretending to listen

to the preacher and waiting, waiting for a chance to sleep on one of the iron beds

lined up like soldiers with white sheets pulled drum tight.

My mom parks our two-tone blue Pontiac outside the liquor store

stocked with golden pints of brandy, port and muscatel.

She checks her lipstick in the rearview mirror.

She makes sure her stocking seams are straight

and my ponytail is so tight it makes my scalp ache.

She makes a beeline down the vomit-splattered street to Baachan’s hotel

past the broken men in broken shoes, in pants tied up with rope.

She does not look at the Army-green trouser leg neatly folded,

safety-pinned, and dangling slackly where a limb should be,

She’s blind to the gap-toothed yellowing ivories, the grey-stubbled chins lined with spittle,

the passed-out drunks lying twisted on the ground just as they fell,

wreathed in the sweet, stale fumes of cheap wine.

“Single Rooms • Daily • Weekly • Monthly”

reads the sign on Baachan’s hotel.

The door is checked and chalky with age and the entrance reeks of piss.

"Don't touch the walls," my mother says. She gathers her skirts tightly

so they will not brush the stamped metal wainscotting

painted institutional green and stained with grease from many hands.

Baachan is waiting for us at the top of the stairs,

at the end of a long hall lined with bleak single rooms.

A tiny woman, skinny as the broom she wields,

as crooked as the teeth jammed any which way into her mouth.

“Yokatta, ne!” she says when she sees us. “Isn’t it good.”

“Namu Amida Butsu, I pay homage to the Buddha,” she says.

And as she beams, it IS good. All of it—

the ten kids she raised in this skid-row hotel,

the drunks, the deadbeats,

the bums who call her “Mama” and eat her free Sunday chili,

a nervous mother, a little girl with eyes like cameras—

nothing escapes Baachan’s compassionate view.

As Baachan and I walk to the store,

a drink-reddened man blocks our path.

“Hey Missus! How’s it going?” he bellows.

“Ahh, Bru-ran-San, Mr. Brown! Longu time no shee.”

She chuckles and bows, then peers deeply into his eyes.

“How you doing? Okeh?

The man shrugs, “Well, you know….”

He ducks his head and squints at her hopefully, “I’m trying, right?”

Baachan pats his arm. “You good man. Rememba dat, you be okeh.”

The man nods. Then he notices me peeping from behind Baachan’s purse.

He begins to rummage frantically through his pockets.

Does he have a gun, I wonder. Is he going to rob us?

“Wait, wait, I’ve got it.” He pulls a butterscotch candy

from a sweat-stained pocket and holds it out to me.

My knees lock in resistance as Baachan gently pushes me toward the man.

“Aren’t you a little cutie!” the man says, bending down and

wreathing me in the sickly sweet aroma of stale muscatel.

I look at the candy. The wrapper is crushed and covered with pocket lint.

Don’t touch! It’s got germs, Mom would have said. But she’s not here.

I look up at Baachan. “Tek it, tek it,” she urges. “Say ’sank you.’”

“Thank you.” I take the candy with the tips of my fingers,

careful not to touch the man’s hand.

The man’s red-rimmed eyes well up.

He straightens and says to Baachan,

“You know, my little girl was about that age…”

Baachan holds his gaze for a long moment.

“Sori, I so sori. You good man,” she says, and bows to him.

Mom would have made me throw out the candy

But I unwrap it and stick it in my mouth.

It’s so old that my teeth sink

through a layer of gummy softness

before hitting the clean crunch of butterscotch.

I savor the sweetness as I follow Baachan down the street.

*Previous versions published in Empty Shoes: Poems on the Hungry and Homeless (Popcorn Press 2009) and Standing Strong! Fillmore & Japantown (Pease Press 2016). This poem is copyrighted by Shizue Seigel.

Baachan Grandma

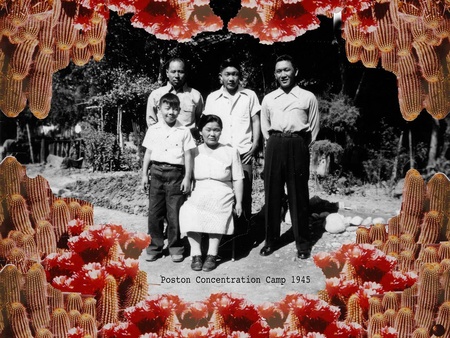

*Dedicated to my Pismo Beach/Morgan Hill baachan, Umematsu Yokote Tsutsumi Shikano

Baachan. Grandma. Of you I know mostly facts, not feeling.

Your eyes were like jet—brightly opaque.

They saw all without a hint of weakness.

Gaman. Endure. Persevere beyond hope.

Kichinto shinasai. Do it just the right way.

The year before you died in 1981

you thought you were a little girl again, back in Japan.

You dreamed you died but the gatekeeper sent you back

because you hadn’t suffered enough.

They say Nirvana, the Pureland, awaits

anyone who can say three times from the heart

Namu amida butsu. Namu amida butsu. Namu amida butsu.

I put my faith in the Buddha.

In 1913, you put your faith in a man who called you to California

He sparked the wanderlust born into your blood—

The seed of disappointment and the egg of hope conjoined

in some Hawaiian canefield that your parents endured just long enough

to serve out their contract and drag themselves back home.

But you could not be contained by two-acre rice plots in a mountain village.

When the man from the next village called you

to join him in California, you went.

He was plain but sturdy—courted you with photos of horse and plow,

haystack and wagon, wooden irrigation flumes,

and a Japanese woman in a billowing shirtwaist and a long Western skirt.

So you packed your kimonos, and steamed over the long ocean to the big land

where he bought you a hat with ostrich plumes,

and a jacket with muttonleg sleeves.

You placed your faith in this man, this life, this land

and it was good—though children died and crops failed.

You prayed to the Buddha in the dining room and Kamisama in the kitchen.

When plows turned up arrowheads, you brought a Shinto priest 200 miles

to placate the spirits who’d roamed the land before you.

You and your husband were kigyo shin, enterprising spirits.

Isshoni, together, Issho ken mei, you worked together, with all your might.

Worked around the alien land laws, shipped your produce to L.A.,

dressed your sons in sailor suits and your daughter in silk stockings.

You bought property in town near the Buddhist church

that became San Luis Obispo’s mini-Japantown,

with a Nihonjin barbershop, fish market, pool hall, hotel and gas station.

You planned to populate your own little community—

your kids would become the pharmacist,

the seamstress, the garage mechanic….

Where did your faith go in 1933 when your husband

drove into a telephone pole? A silly little accident

until his stomach filled up with blood. The hospital would not x-ray.

The insurance company would not pay double indemnity for accidental death.

You said he might not have died if he’d been white.

You said it only once out loud, but your children say

you often walked the cliff edge and stood for long moments

at the brink of the sea looking west towards home.

Gaman and ganbatte. Suck it up. Never give up.

Put your faith in 140 acres and four children.

You made your 13-year-old learn to drive

so you could keep up the mortgage on your Japantown property.

Throughout the Great Depression you visited tenants who often said,

“We can’t pay this month; business is too slow.

Yoroshiku onegai shimasu. We are forever in your debt.”

Long after the war, Issei ladies bowed and you bowed back.

I was too young to notice who bowed deeper.

You hired a new foreman to help manage the ranch.

Lettuce, peas and cantaloupe thrived in the moist sea air.

Then a white man bought the land out from under you,

plotting to turn a profit by doubling the lease.

But you told him no. Moved off the land and up the hill. Built another house.

You put your faith in your community. “Let’s all tell him no!”

For a full year, no nihonjin leased in your place.

The land lay fallow until the landlord knuckled under

and let you come back at the same price.

That kind of Jap conspiracy does not go unpunished.

In 1942, Pearl Harbor forced you from the coast

You moved outside the curfew zone,

first five miles east—then 100 miles more—

trying to stay ahead of the barbed wire until it finally snagged you

just outside Fresno, and cast you east of the Colorado River

where—over the objections of displaced Indian tribes—

you were imprisoned with thousands of others in the searing desert,

trapped amid tar-paper shimmering like a mirage that would not dissolve.

Tucked inside your shoe was all that remained of your previous life.

A clipping: “Jap house burns to ground.” And cash from the realtor who

bought your Japantown, saying, “You’ll never be able to keep up the taxes.

You already put $80,000 into it. Let me take it off your hands for $2000.”

He even put his name on the hotel your husband had built.

How many dollars did you have left when they let you out in 1946?

“Don’t go come back to the coast,” friends warned.

“They’re shooting out our windows at night.

They won’t sell us gas or fertilizer.”

So you came north to start again—at 57 on your knees—

sharecropping strawberries in another tar-paper compound.

In ten years you saved enough to buy ten acres of your own.

Gaman, gaman and gaman some more. Persevere in the face of hardship.

Until it becomes shinbo—endurance as a way of life.

Maybe your soul wore away in pieces too small to notice

until all that was left was efficiency,

washing the rice, “goshi, goshi, goshi,” scrubbing the grains three times firmly,

snipping your scissors in quick clips to make crepe paper petals,

combing black dye through your hair with a toothbrush,

mentally plotting the most precise way to live without wasted motion.

Chanto shinasai! Do it right.

How much suffering was enough?

Your cactus collection still grows near the garbage can.

*Previously published in Endangered Species, Enduring Values, Pease Press 2018. This poem is copyrighted by Shizue Seigel.

© 2009 & 2018 Shizue Seigel