I am curious about what prompted you as a third year high school student to return to the US on your own? What was the reaction of your parents? Where did you go? Where did you study?

Despite the tragedies my father had faced, he strongly believed that the USA had the best education system in the world and encouraged me to study in the country. In order to prepare for the goal, I was sent to a junior - senior mission school in Fukuoka, where English language (not content courses) was taught by American missionaries and went to the American Center for extra language lessons.

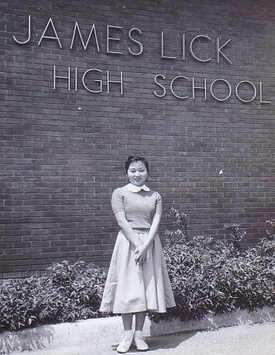

After arriving in the U.S., I stayed with my aunt’s family in San Jose and attended James Lick High School. In 1958, I entered University of California, Berkeley and graduated in 1962.

Can you please talk about your academic career? In the 1970s, what kind of Japanese American literature were you studying? Do any particular writers stand out for you? What did you learn about the JA experience?

A year after I graduated from UC Berkeley, I married a Japanese scholar whom I had met and became engaged to while an undergraduate. Those were the days, few girls went to 4-year colleges and pursued a career, particularly in Japan. I was determined to be independent and upon returning to Japan, found a job at a language school, and then a conference interpreter, which enabled me to become a university lecturer. I acquired a graduate degree in teaching English in Vermont while working at the Japanese university.

In 1978, I discovered the Japanese translation of Yokohama, California by Toshio Mori. The original English version was published in 1949, but was not available until the University of Washington republished the English version in 1985. However, I acquired the xerox copies of the English version in 1978 as the translator, Prof. Oohashi was kind enough to send them to me.The collection of nine short stories took place in Oakland, California, where I was born and I was curious about my hometown.

Around the same time, I discovered that two Asian American Literature/Culture study groups had been founded in Japan, and I joined them as well as the AAAS (Association for Asian American Studies), which was quite active in the U.S. My membership in these three associations helped me to further my research and teaching.

Janice Mirikitani struck a chord with me being a Sansei, whose mother refused to talk about the internment. My book, Singing my Own Song (Yamaguchi Shoten, 2000) consists of my three papers on Japanese American/Canadian writers, Janice Mirikitani, Joy Kogawa, and Kyoko Mori.

As I interviewed Janice (1941-2021) at Glide Church a few times (1990, 1991, 2019) and met her with her daughter in Japan (2015), she stands out especially to me. But there are a number of other Japanese American writers I interviewed at their respective homes, e.g., Yoshiko Uchida in Berkeley in 1990, Jean W. Houston in Santa Clara around 1990, Michi Weglyn in New York in 1991. They remain fresh in my mind as they made an impact on me.

I had the pleasure of getting acquainted with (Canadian poet/author) Joy Kogawa in 1999 as she was a frequent invited guest speaker at Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto and I wrote a paper, “Trust, Justice and Mercy - The Journey of Joy Kogawa”, which was published in Singing my Own Song.

The poetry of Mirikitani is unknown to me. Any particular work of hers that is especially meaningful to you?

As I wrote in my paper, “Four Generations of Japanese American Women in the Work of Janice Mirikitani” (Chapter 1, Singing my Own Song, 2000), she dedicated the poem, “Breaking Silence,” to her mother who finally testified before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Japanese American Civilians in 1981, after 40 years of silence.

How did your research and education evolve from there? I am very interested to know what specifically took you to Dachau?

My interest in Japanese American literature stems from wanting to know about my family roots, especially about my family’s internment experience. I presented many papers related to these topics at academic conferences both in Japan and abroad in the 80s and 90s. My research on the internments stretched to Canada, starting from Joy Kogawa (2000) to more contemporary writers like Kerri Sakamoto (2005) and Sally Ito (2005.)

In 2010, I was officially retired from teaching at Kyoto Sangyo University where I worked for 35 years, lecturing courses such as “Ethnic Identity in Asian American Studies,” and “Multicultural Society,” etc. However, even after my retirement, because of my research on internments, I have been asked to give talks on human rights issues in Japan and abroad.

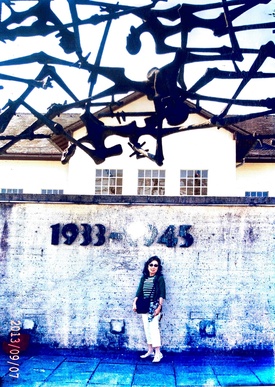

I am not certain what led me to visit Dachau in 2013, although I can think back and recall three things that I experienced in 2006 - 2007 that motivated me to go: first, my participation in a pilgrimage to Tule Lake (2006), the site of a former camp where I was held with my family; second, my visit to Fort Lincoln, now UTTC (United Tribe Technical College) in Bismarck, North Dakota, where my father was interned separately; and third, the WRA and DOJ files I received from NARA (2006).

Actually seeing genuine copies of my family internment documents and being at the places where my father and the rest of the family were internedtruly made me want to visit a concentration camp. I chose to go to Dachau because it is located next to a nunnery where I could stay as I happened to have an acquaintance there. Later, I learned that the over 4,000 surviving Jewish inmates there were rescued by Japanese American soldiers.

Moreover, I often use one photo I took there of a group of local high-school students on a field-trip as part of their history course curriculum. I realised it is important for youth to be aware of history, even if it is about the dark side.

What has been keeping you busy since retiring from Kyoto Sangyo University?

I retired in 2010 from teaching, but for 35 years (1975 - 2010) I taught English and Communication as well as courses such as Multicultural Society and Ethnic Identity in Asian American Studies. (I took a sabbatical for one year and a half). Since retiring, I have been a guest lecturer at various universities and public lecture halls.

What does the internment mean to you now, 80 years later? Are there still questions that you are looking for answers to?

As December, 2021 and February 2022 marked the 80th anniversaries of Pearl Harbor and the issuance of Executive Order 9066, respectively, I was asked to give a lecture at a women’s college, and was interviewed by a major newspaper and TV station. I was more surprised by how Japanese media had planned a special program for something that had happened such a long time ago.

I do not think there is one concrete answer to any historical incident, (as everyone goes through his/her unique experience that is impossible to convey,) like we are now witnessing the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It is the ordinary people who get hit the hardest so we have to keep on saying, “No war, what-so-ever!”

Furthermore, as we continue to see racial/ethnic discrimination rampant all over the world, as I have travelled all over the world and become acquainted with people of different cultures, I realize it is important to know that there are all kinds of people and everyone is unique. I therefore feel as a person who has lived and experienced internment thatI have an obligation to talk about my family history whenever asked.

What has it been like for you to live and work in Kyoto as a Japanese American?

When I returned to Japan in 1962, the country was extremely backwards and conservative. Now after 60 years, Japan has improved in many ways, particularly gender issues such as equal opportunities and career choice, but still it has a long way to go.

Looking back I remember feeling uncomfortable in workplaces as well as just being a woman then. In Japan, many people are not aware that I am a Nikkei, and simply treat me as a Japanese career woman with extensive experience of living abroad. An American friend of mine said, “You are more a returnee, rather than a Japanese American.” If I write my Japanese name 野崎京子, it reflects one half of me, a Japanese, unless I write my English name, Kyoko Norma Nozaki, then a Japanese American. In short, I am a minority of minorities.

In the end, have you found your roots?

I have found I have roots in two countries: Japan and the U.S.A. With respect to the question, “In which country do you feel more at home?”, my answer is “I feel comfortable and uncomfortable in both countries.”

Final question: have you forgiven America for what it did to JAs?

In the past, when my parents were alive, I asked them the question and they never answered me concretely, but the fact they sent me to the U.S.A. to enter the University of California, Berkeley, suggests that they did not lose faith in the country.

As for me, I always believe one should forgive people or nations for their conduct, but it is important to remember such events. That is why I am committed to telling my family history whenever asked.

© 2022 Norm Masaji Ibuki