“Mr. Commissioner….

So when you tell me I must limit

Testimony

When you tell me when my time is up,

I tell you this:

Pride has kept my lips

pinned by nails

My rage coffined.

But I exhume my past

to reclaim this time.

My youth was buried in Rohwer,

Obachan’s ghost visits Amache Gate.

My niece haunts Tule Lake.

Words are better than tears,

So I spill them.

I kill this,

The silence…”From “Breaking Silence” (for my mother) by Janice Mirikitani (1941-2021)

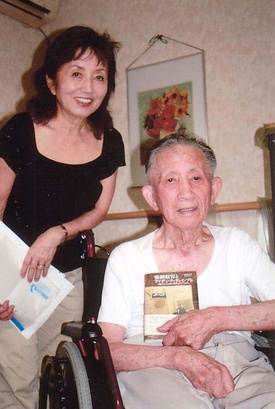

If anyone knows about the struggles of living with the dual identity of living as a Japanese American in Japan, it is retired academic Kyoko Norma Nozaki (nee Tanigawa).

Born in California, imprisoned at Tule Lake, deported to Japan, she returned to the US where she received her university education at UC Berkeley and Vermont, then returned to Japan where she taught “Ethnic Identity in Asian American Studies,” and “Multicultural Society” etc. for 35 years. Today, the 82-year-old lives in Kyoto’s Sakyo Ward with her husband, Dr. MItsuhiro Nozaki.

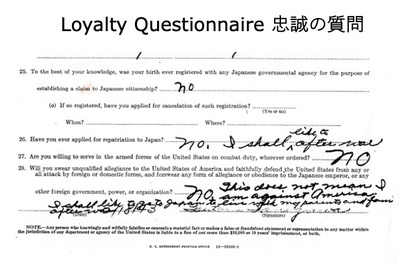

As with many Japanese Americans at the time, Tsutomu filled out a loyalty form issued by the US government asking if an individual would be willing to serve in the US military on combat duty wherever ordered (#27) and if they would swear unqualified allegiance to the United States, forswearing allegiance or obedience to the Emperor of Japan (#28).

Nozaki's father answered “No” to both questions and left a note on the questionnaire that he did not intend to go against the United States. He thus became a so-called “No-No Boy.” Nozaki's grandparents were first-generation immigrants who came to the U.S. mainland after working in a Hawaii sugarcane field, and had returned to their hometown in Fukuoka Prefecture before the war. Nozaki's father was worried about what the consequences might be for his family in Japan if word got out there that he had renounced allegiance to the country.

When Nozaki and her family were moved to Tule Lake concentration camp, father Tsutomu was sent alone to a Fort Lincoln Department of Justice (DOJ) camp that was mainly for people considered to be higher security risks. The family didn’t reunite until four months after the war on Dec. 29, 1945, aboard the USS Gordon.

Nozaki said that while her father loved the United States, he did not intend to live there again. His anger about the two loyalty questions and the U.S. government’s attempts to get individuals to obey it by depriving them of their jobs and homes never faded. A meat and potatoes man who never touched sashimi, Tsutomu continued to enjoy American brands like Skippy peanut butter, Snickers, and Butterfingers. Still in possession of the trunk that he purchased at the outset of WW2, number 21504 still visible in faded blue, Tsutomu passed away in 2011 at age 101.

《From Kyoko: My answers are recorded in my published book in Japanese, 『強制収容とアイデンティティ・シフト:日系二世・3世の日本とアメリカ』 (Kyosei syuyo and Identity Shift: Japan and America Through the Eyes of a Nisei and Sansei), [世界思想社, 2007]》

* * * * *

Can we begin by getting some details about your family? Where did they come from in Japan and when did they arrive in the US?

Both my paternal (Tanigawa) and maternal grandparents (Kuratomi) migrated to Hawaii from Fukuoka in 1904. They worked in sugarcane plantations until 1906, when my paternal grandparents moved to the mainland U.S.A. They settled in Watsonville, California, where my father (Tsutomu ‘Storm’ Tanigawa) was born in 1909 as their second son.

How did your father become a strawberry farmer? Can you talk a bit about your mother?

As my paternal grandparents had saved enough money to buy a house and parcels of land in Japan, they were back in Japan while my father and his brother were finishing secondary schools in California.

Later, my father, his elder brother, Kazuo, and theirrelatives leased and later owned the land in Watsonville, and subsequently in Mt. Eden (later annexed by Hayward). They had to move to different farm plots every three or four years because strawberries do not grow well on the same land many years in a row.

My mother (Katsue Kuratomi) was born on July 4, 1916 in Oxnard, California, but raised in Fukuoka, Japan from the age of six. Her Japanese name (勝枝) means “victory branch,” as if to commemorate American Independence Day.

She was a nursing student when she met my father who was visiting his parents in Japan. They married in 1936. She gave birth to two children—Hiroshi Barbi, my brother, in 1937, and me, Kyoko Norma in 1939. (Bilingual Complex, 2019, pp.45~51)

Where was your family interned? Were you interned at Tule Lake? Where was your dad sent to alone?

When Executive Order 9066 was announced on Feb. 19, 1942, we were sent to the Tanforan Assembly Center. My parents were Nisei, ages 33 and 25 respectively, and my brother and I were Sansei, 5, and 2, upon being interned. Then in September, we were assigned to Topaz Relocation Camp, Utah, where we stayed for one year until Sept. 1943. From Topaz, our family (father, mother, brother, and myself) were sent to Tule Lake camp.

During our days in Tule Lake, my father alone was apprehended by the FBI in Feb. 1945 and sent to Fort Lincoln DOJ camp in Bismarck, North Dakota. The rest of the family remained in Tule Lake until we met my father on board the USS Gordon on Dec. 29, 1945.

Why did your family return to Japan after WW2? Where did you settle? What did your father do for work?

My father was at the time disillusioned by the way he had been treated by the American government, particularly at being asked about his loyalty in Questions 27 and 28, and had repeatedly said, “They should have asked the questions before they placed us in the camps.” Until then, he had always felt he had been a law-abiding American, in fact he had grown up in an environment where he had not experienced any racial/ethnic discrimination.

So when he was released from Fort Lincoln DOJ camp in Dec. 1945, he made arrangements for all of us to go to Japan (my mother, brother, and I were still at Tule Lake camp). We met on board the USS Gordon which departed for Japan on Dec. 29, 1945. The ship arrived in Kurihama on Jan. 15, 1946. We took a train to Fukuoka, where my grandparents lived. As I was a 6-year-old child, I do not remember the details, but my father said, “as the train passed Hiroshima and when he saw the city, he confirmed the reality that Japan had lost.”

Almost as soon as we started living with my grandparents on the outskirts of Kurume, Fukuoka, he was recruited by the occupation forces as an interpreter. As a defeated country, everything in Japan had to be approved by the occupation forces of the U.S. government. English had become extremely important as it wasthe only way to communicate. He had managed to use his linguistic skills most efficiently.

The occupation was dissolved within a year but his American boss found him so likeable and capable that he recommended him to work at an American films distribution firm, which was very popular as it was then the only entertainment industry in Japan. Later he became a general manager, which led to me meeting Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio, the American baseball major leaguer, who came to Japan on their honeymoon, in Feb. 1954. (Bilingual Complex, 2019)

In the Mainichi newspaper article, it is noted that your dad saw himself as American. Can you please expound on this?

As I said, he grew up in multi-ethnic communities at Watsonville, Mt. Eden, enjoying friendships with Euro-Americans of many different ethnic backgrounds (e.g. German, Spanish, Portuguese), and playing together with b.b. guns and availing himself to rich ethnic cuisines. In fact, he hated going to the Japanese language school after his regular American school, and spent the time swimming in a river.

He did not care much about Japanese culture. In fact he and his brother went to see an American movie on Dec. 7, 1941, after dropping their wives at a Japanese movie theater. Evidence of his American way of living can be found in his answers to Questions 23 and 24 in the US-issued questionnaire, written from January to February 1943 at the camp. (DOJ file from NARA)

For Question 23, he listed “Red Cross, Community Chest, Relief, Hayward” (as written) as organisations he regularly contributed to. In response to Question 24, he wrote New World Sun, Oakland Tribune, Look, Life, and Saturday Evening as magazines and newspapers to which he had subscribed. He often told me that he had never participated in any kind of pro-Japanese activities, e.g. Shinnichi and Wasshoi gumi, etc. and that is why he could not comprehend why he got picked up by the FBI.

His favorite food was meat and potatoes, particularly T-bone steak and baked potatoes and he stayed away from fish, never touching sashimi. Even for snacks until the end of his life, he continued to enjoy American brands, including Skippy peanut butter, and chocolate bars like Snickers and Butterfingers. He had a checking account with the Bank of America, and each year he would write a check to mail order See’s Candies for his friends and relatives for the holiday season, which continued until 2011, when he passed away at the age of 101. I still miss this ritual and the box of See’s chocolates, another American item which my father was truly fond of. (Bilingual Complex, 2019, pp.52~59)

Did your father ever forgive the US government for what it had done to Japanese Americans? Did he ever return to the US to visit?

When my parents received a check for $20,000 with a letter of apology from President Bush in 1990., he said thoughtfully, “this is nothing compared to what we went through and lost.” Whether he forgave the US government, I could not tell. But he had always been a fair and compassionate person and tried to see the good side of people, and described himself as an optimist, “gokuraku tonbo” (an easy going fellow). The only thing he regretted was the death of my brother who was killed in an accident in May 1946, 5 months after we arrived in Japan. (Bilingual Complex, 2019, pp.23~26)

After the war, he visited the USA a number of times on business trips and enjoyed family reunions quite frequently.

© 2022 Norm Masaji Ibuki